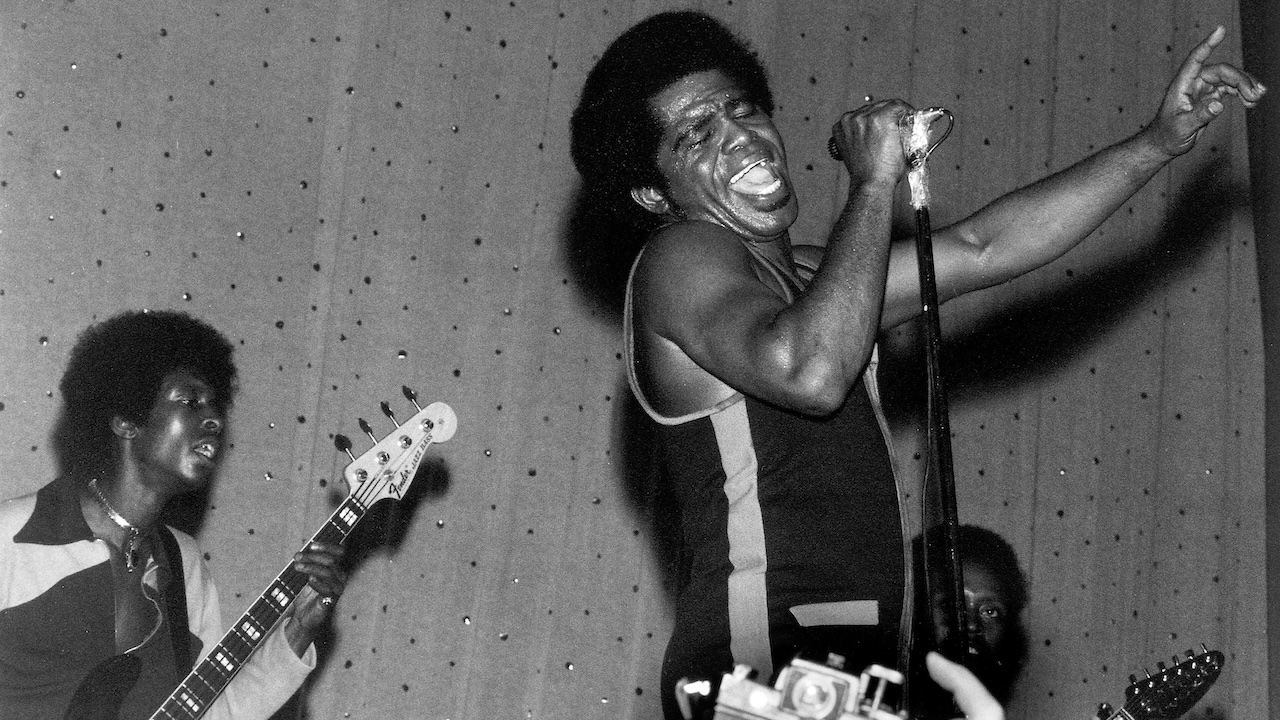

“He fined me 50 bucks and fired me, even though I didn’t mess up”: The bassists of James Brown reveal what life was really like playing alongside the Godfather of Soul

Fred Thomas, Ray Brundidge and Bootsy Collins dig into what it meant to play with Soul Band No. 1

Bass Week: There's not much to be said about James Brown that hasn't already been covered by the media, but not enough has been made about the amazing bassists who backed him up throughout his incredible career. More than a dozen low-enders bounced in and out of his band.

Fred Thomas anchored the fort on such hits as Hot Pants, and Papa Don't Take No Mess. The sheer number of hip-hop tracks that use those lines prompted Brown to refer to Thomas as the “most sampled bass player in the world.”

If anyone is warranted to take issue with that statement, it's another Brown alumnus, William ‘Bootsy’ Collins. Bootsy was involved with Brown's band only for a short time, but during his tenure he recorded several anthems, including Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine, Super Bad, and Soul Power, Pts. 1 & 2, which ushered in an era of deeper funk that Collins later incorporated into his work with Parliament-Funkadelic and his own Rubber Band.

Almost as legendary is the iron-fisted manner in which James Brown ran his band. Tales of fines for missed cues and unshined shoes have loomed large in the lore of working musicians since the bass became electrified.

“The last time I got fired was in 1995,” Fred Thomas told Bass Player. “I like to play with my eyes closed. I can just feel and hear better that way – but James was not with that. I usually managed to keep one eye cracked, but that last time he fired me, I had stayed under too long.

“When I did look up, he was right in my face throwing his hand down with his fingers pointing out, and every one of those means you're fined five bucks. He fined me 50 bucks and fired me, even though I didn't mess up!”

Back in 2005, Bass Player corralled Bootsy Collins, Fred Thomas, and Ray Brundidge, to dig into what it really meant to be a soul man in Soul Band No.1.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When did you first encounter James Brown?

Ray Brundidge: “I was 12 years old when Mother Popcorn came out in '69, and my friend and I took a bus to Buffalo to catch James' show. He had a bigger band than the one we have now – three drummers, multiple horns, dancers – and I think Bernard Odum was on bass guitar. That was actually my first concert, and it made me focus on playing music.”

Fred Thomas: “I got a chance to see him live as James Brown & the Famous Flames when I was in high school in Georgia.”

Bootsy Collins: “I met him when I was 15. My brother and I were in the house band at Cincinnati's King Studios, but when James and his band came to town, it was always a closed session. We couldn't get near him, but we would hang out with his group on their cigarette breaks. They were like our heroes.”

“Then one day the band went to lunch while James was in the studio recording Licking Stick-Licking Stick. We were around the door when his road manager, Bud, said Mr. Brown wanted us to come in and maybe lay down this bassline.

“That was my first encounter with him. We worked on it for a while, but we didn't get the chance to put it to tape before the band came back.”

How did you come to be in James Brown's band?

Bootsy Collins: “At first I thought it was a joke when we got the call to play with James that very night – that his Lear jet was on its way to pick us up. His management said they wanted us to ‘play with James Brown,’ but we didn't think they meant it literally. We thought, ‘Even if this is true, we'll probably just be playing our regular set.’

“They didn't tell us the band had walked out, so we kind of crossed the picket line – unbeknownst to us – until we actually got to the gig. Then we started seeing all these long faces – Charles Sherrell and Bernard Odum were there – and it was like, ‘Wow, what have we done?’ James said, ‘I want y'all to play the set with me. How much do you want?’ We had no alternative but to go on!”

Fred Thomas: “When I got to New York in 1965 l hooked up with guitarist Hearlon ‘Cheese' Martin and formed my first band, which I played with until I met James in 1971. One night we were working at this club in Harlem called Small's Paradise, which was owned by Wilt Chamberlain.

“James entered with his entourage, and everybody was hollering for him to come up and sing a song. Sex Machine was the hot record at the time, and he said, ‘Can I count it off?’ We wore him out, and after that he said, ‘I want this band.’ We were rehearsing within a week or so, because Bootsy and those guys were having a conflict with James at the time. He needed a new band, and we were it.”

Ray Brundidge: “I almost wound up in Billy Joel's band instead! They asked me to join, but I was busy with my band and Billy wasn't such a big deal then. A short time later I moved to California, and an old guitarist friend of mine who was in James' band brought me to Mr. Brown's attention. Years later, in 1998, they called me in to play with James so that Fred wouldn't get worn out.”

How did you go about assimilating the tunes and making them work for your own style?

Bootsy Collins: “We didn't go back and study anything. We just played it the way we felt it should be, which brought a freshness, and James liked it.”

Fred Thomas: “I already knew James's music, because my band did all the hot tunes from '66 until I joined. I did my own thing. I never bothered with any fancy stuff because I always did the singing in my bands, and you can't be fancy and sing. I had to discipline myself to stick to the pattern.”

Ray Brundidge: “Basically, you learn from the guy who came before you, and I learned by watching Fred. Everything sounded good, but there wasn't a lot of slapping and popping going on, so I figured that could be my niche.

“The first time I tried it, I turned up the treble on my amp so I could get a little pop. But James wasn't used to it and said, ‘Son, that doesn't sound like a bass. You don't know how to adjust an amp – let me do it for you!’”

What was it like to step onstage with Soul Brother No. 1 for the first time?

Bootsy Collins: “I had been playing with everybody who wanted to be James Brown, but it took me a while to realize, I'm actually up here onstage with the James Brown. He told us, ‘All I'm going to do is call out the songs, drop my hand, and y'all are going to hit it,’ and that's actually what happened.

“After that first show he reassured us that everything would be fine once we learned how he used his body movements for the show. That was actually the first and only time he reassured us that everything was going to be on the one!

“Once we learned the show for real, he reversed the psychology on us – like we weren't happening – but years later I realized that it only made us tighter.”

Fred Thomas: “We rehearsed for a week in New York and then we went to Toledo, Ohio, and played the first show. You had to have a memory like an elephant to remember two-and-a-half hours' worth of hits, and dancing cues, but after that, all the butterflies were gone. To go from playing clubs to audiences in the 10,000 range, it was like, ‘Wow – this is showtime!’”

In the early years, how were bass parts conceived when a new James Brown song was being fleshed out?

Bootsy Collins: “James would give you some grunts, and then you'd have to play it back and say, ‘Is this what you're talking about?’ As long as what you played made him feel good, that was it – whether it was what he meant in the first place or not.

“The rhythm section didn't write anything down. We played by ear. Everybody seemed to like us for doing it that way, so that's what we built on.

“The first new James Brown song I played on was Sex Machine. We were on the bus after a gig when he and Bobby Byrd hopped on. They didn't have any paper, so they tore up a paper bag and started writing the lyrics.

“My brother and I were sitting behind them with our guitar and bass, fooling around with the groove. We went straight from the gig to the studio, and that's where it all started happening.”

Fred Thomas: “The line on Doing It to Death (Funky Good Time) is the line I felt, but mostly, you played what he told you to play. If the line wasn't happening, you found your own way to make it funkier by attacking it differently.”

“For instance, he gave me the Good Foot line, but it sucked. It wasn't saying jack, so I put a little James Jamerson-type ghost-note in there. It was up to me to make it happen, and I think that was the case with all of his musicians.”

Fred, inside Brown's Star Time box set, it says the bassist on Papa Don't Take No Mess was either you or Charles Sherrell. Can you clear that up?

Fred Thomas: “It was me – Sweets doesn't play like that. He has more of a thump and a light picking thing, whereas my notes are more laid down. Sweet Charles did play on The Payback, though. James gave him that line, but Sweets put a little pickup note in there that changed the feel and made it flow better.”

Can you give us a good story about being disciplined by James?

Ray Brundidge: “I was studying Fred a lot, and I was amazed at the tone he was getting. Fred plays ‘down’ with his thumb. That was something I had to learn. James said, ‘You play good, but I want you to play down.’”

“Most fingerstyle players like myself sort of play ‘up’ – that's the direction the fingers are going when they pluck a note. But James thought like a drummer – that when you are playing on a downbeat, your thumb should literally strike down on the string.

“That cleans it up so you aren't playing all those extra notes. James mentioned that he was going to charge me $25 every time he caught me not playing ‘down’. After a couple of fines, I learned it's better to give him what he wants!”

Jim Roberts was the founding editor of Bass Player and also served as the magazine’s

publisher and group publisher. He is the author of How The Fender Bass Changed The World

and American Basses: An Illustrated History & Player’s Guide, both published by Backbeat

Books/Hal Leonard.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

“One of the guys said, ‘Joni, there’s this weird bass player in Florida, you’d probably like him’”: How Joni Mitchell formed an unlikely partnership with Jaco Pastorius

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)