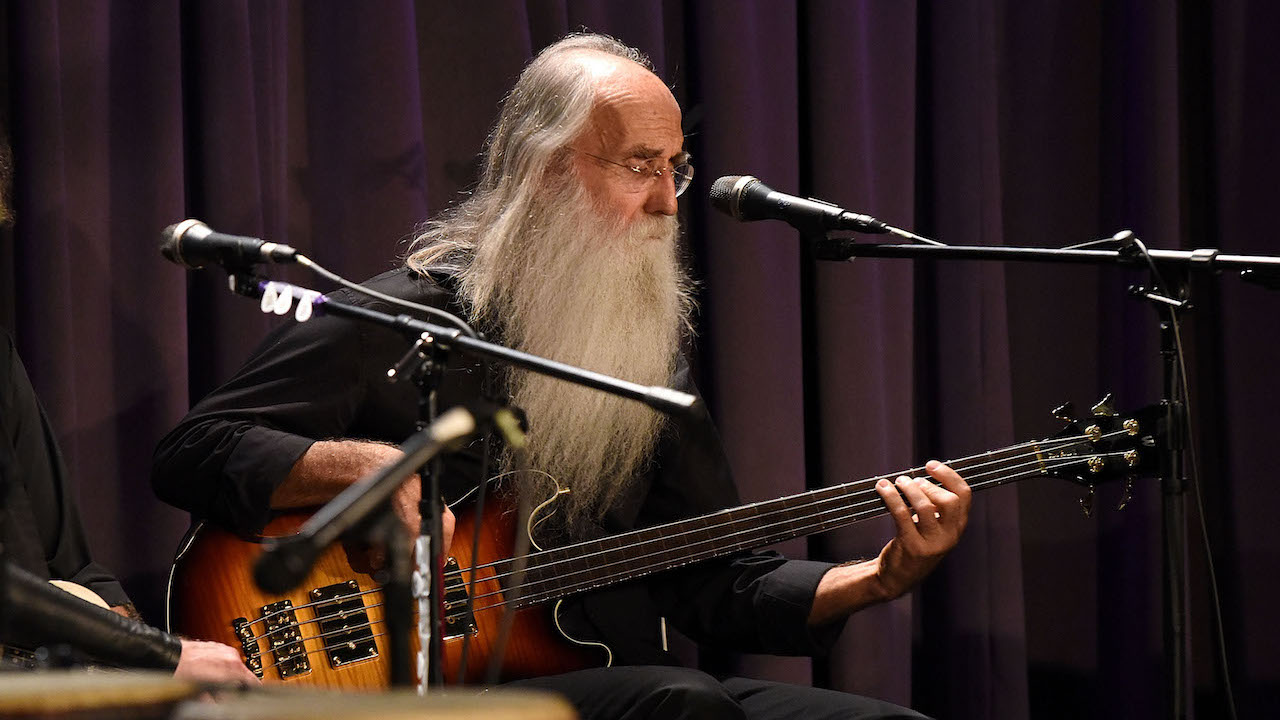

“What you hear on Stratus is pretty much the first take. Tommy Bolin's guitar playing is some of the best that ever was”: Legendary sideman Lee Sklar reveals the studio secrets behind his incredible career

The legendary bassist looks back at five decades of studio work on hit songs by James Taylor, Jackson Browne, Phil Collins, and many more

With over 2,000 albums to his credit, Lee Sklar is one of the most prolific session bassists in modern music. His work dates back to the late '60s, but he really gained momentum in the early '70s after teaming up with James Taylor.

Sklar's basslines have since graced the music of Linda Ronstadt, Hall & Oates, Jackson Browne, Phil Collins, Aaron Neville, Randy Newman, Lisa Loeb, Vanessa Carlton, Willie Nelson, LeAnn Rimes, and many others. He also supplied the rumbling force that relentlessly drove fusion drummer Billy Cobham’s Stratus.

Sklar got his start in music as a child prodigy pianist, but piano took a back seat after his music teacher urged him to try upright bass.

“When he pulled out a string bass, I said, ‘You gotta be kidding,’” Lee told Bass Player. “As time went on, there was something about the sonic quality of the bass and the position that it embraced in the orchestra. I ended up loving it.”

At 16, Sklar got his first bass guitar, a St. George, and in the late ‘60s he began performing at clubs and parties with local Los Angeles rock bands, but meeting James Taylor changed everything.

“I was in a progressive hard rock band called Wolfgang, and at one point we were looking for a singer. James hung out at one of our rehearsals and we jammed with him. We were really looking for more of a hard rock singer, but we recorded a version of his song Country Road.”

Taylor had already completed his first album, and when it was released, Sklar was invited to play with him at the Troubadour.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I went to James's manager's house and rehearsed with Russ Kunkel, whom I had met a few years before. When we played the show it was only half full; you could have driven a truck through the place and not hit anybody. But then, Fire and Rain was released, and when they had us come back it was so crowded that they almost had to close the club down.”

Then there was an offer for a six-week tour, with Sklar, Kunkel, Danny Kortchmar on guitar, and Carole King on piano. “We started touring, thinking it would be six weeks. It turned into 20 years!”

Taylor's success ushered in an era of young West Coast songwriters like Jackson Browne and Warren Zevon, and producers and artists who liked Taylor's sound would hire Kunkel and Sklar to play on their records.

When Carole King moved on, Craig Doerge joined the group of oft-called session players that became The Section, with whom Sklar recorded three albums.

In addition to volumes of studio and television work, Sklar has been a tireless touring musician; currently he's on a lengthy stint with Lyle Lovett. Somehow, he has also found time to be involved in his own band, The Immediate Family.

In spite of his impressive resumé, Sklar is modest when it comes to the qualities that have made him so accomplished. “I don't see anything special going on. I'm just blessed with the career I have.”

On studio sessions, are you usually given a written part to play?

“It runs the gamut from a note-for-note manuscript, to a chord sheet, to a Nashville number chart, to nothing. It can be a real drag when a lot of your energy is spent trying to learn the song, but if you have some kind of basic chart you can immediately start being creative.”

Do the artists you work with tell you what they want?

“I'm pretty much left to my own devices. One of the great things about music is being in a room with a band, kicking ideas around, and developing songs. So much of that is lost now when you just go in and play to a click track.”

If you had to pick one recording of yours that captures your true nature as a bass player, which would it be?

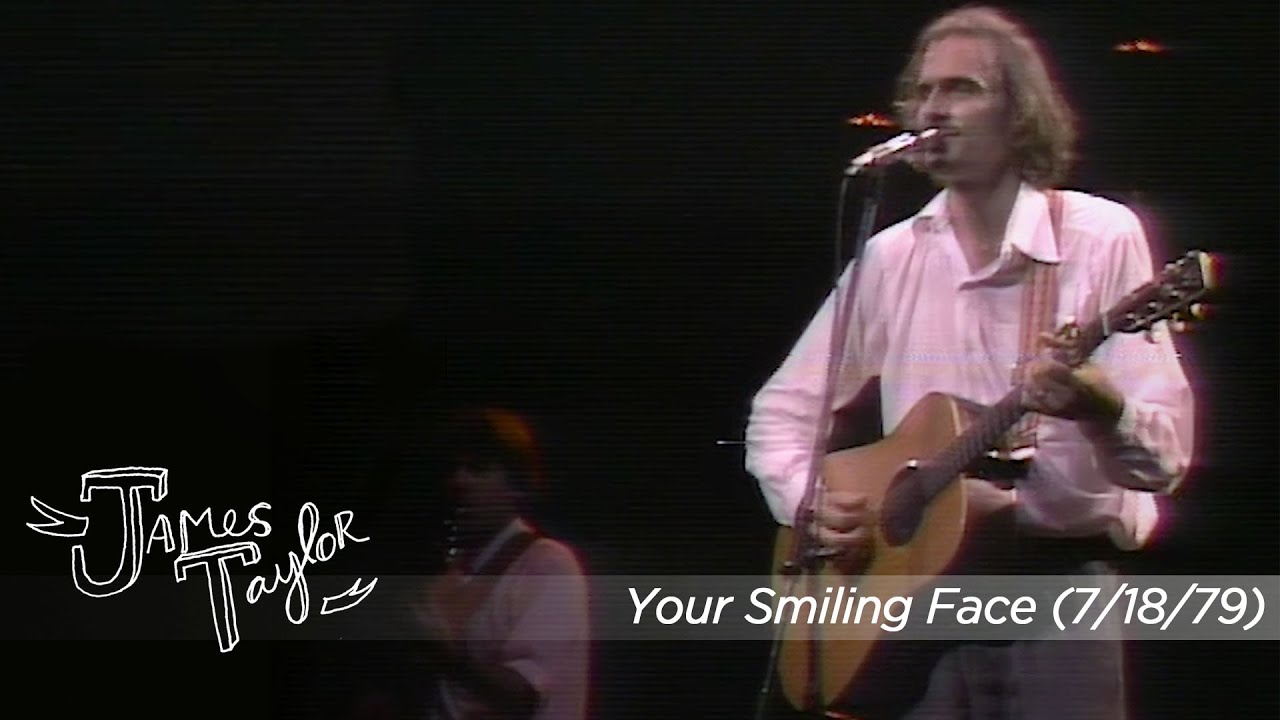

“There are songs like James Taylor's Your Smiling Face where everybody says, ‘Oh, I love that bass part.’”

Why does that stick in people's minds?

“There's something about it that feels good; it has a vibe that people like. When we play that live, in the section where it is just voice and bass, the audiences start waving their arms and singing along.

“I'm not a good judge of what I do; I just let the audience go with it. On that song, I think it's just one of those lucky moments that are few and far between.”

Tell us about your autograph-covered ‘Frankenstein’ bass.

“It was assembled from different parts, but it's one of the best basses I've ever played. It started with a Charvel Precision-style body, and its neck, from a '62 Fender Precision, was re-shaped by John Carruthers into a '62 Jazz neck.

“I walked around his shop looking at fret wire, and I asked if we could try mandolin wire. Over the years, I have converted all of my basses to mandolin frets. I love the way they feel, since I like to glissando, and it's so minimal – especially once they have worn down. You can almost allude to fretless – put on a little harmonizer, and all of a sudden it sounds like a fretless.

“We put a pair of early EMG reversed P-style pickups where Jazz Bass pickups would normally go. I figured reversing the pickups would even out the tone, given the higher frequency nature of the G and D strings. That's a big part of why it sounds good. We put the two 9-volt batteries where the single P pickup would have originally gone, because I didn't want to rout additional holes in the body.”

In addition to the Frankenstein, you’re often seen with a Dingwall 5-string.

“Sheldon Dingwall's 5-string basses, which incorporate the Ralph Novak fanned-fret system, have the best-sounding B string of any bass I have ever heard.

“B strings are usually disappointing to me, with more air moving than note, but on these the note is absolutely there.”

What are some of the moments in your career that you think of as outstanding?

“Stratus with Billy Cobham – bass players always want me to talk about that. I got to know Billy when The Section went out on a tour opening for the Mahavishnu Orchestra. When he had the opportunity to do a record of his own, I think he had Stanley Clarke in mind for the bass, but for some reason it didn't work out.

“I had never really considered myself a chops monster, and those guys didn't need one. They needed someone who could hold down the bottom, and that bassline just fell into place. We finished the whole album in three days; I did two days, and then Ron Carter played on some big band tracks.”

“What you hear on the album is pretty much the first take of every song, all done live without overdubs. Jan Hammer is one of the most gifted synth players, and Tommy Bolin's guitar playing is some of the best that ever was. For them, that bass part just ended up being a foundation that holds things in place while they went off.

“To this day, every time I play that lick in the studio, the drummer salivates and jumps on it, and everyone wants to play that tune. It's one of those things that transcends whatever you thought it would be, a pivotal record in the jazz-rock fusion idiom. Spectrum still holds up like nobody's business.”

Nick Wells was the Editor of Bass Guitar magazine from 2009 to 2011, before making strides into the world of Artist Relations with Sheldon Dingwall and Dingwall Guitars. He's also the producer of bass-centric documentaries, Walking the Changes and Beneath the Bassline, as well as Production Manager and Artist Liaison for ScottsBassLessons. In his free time, you'll find him jumping around his bedroom to Kool & The Gang while hammering the life out of his P-Bass.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“I was playing stuff I don’t think James Brown understood. He told me, ‘You have to play the one – you’re playing too much’”: Six years after he quit touring, Bootsy Collins reflects on James Brown and George Clinton, and what he gets out of playing today

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)