“Jaco was Joni’s liberator, but she wanted the bass to play a greater part in holding down the groove”: Larry Klein on how he handled the challenge of replacing Jaco Pastorius in Joni Mitchell’s band

The session ace-turned producer began working with Mitchell in 1981, soon after her last album with the “world’s greatest bass player”

It was 1972, and the turbulent ‘60s were giving way to the decadent '70s. Nixon was in the White House, and the Los Angeles home of Hugh Hefner's international Playboy Club – newly relocated from Sunset Boulevard to Century City and frequented by the likes of Johnny Carson – was a shining beacon of swinging bachelor-pad possibilities.

25 miles away, in suburban Monterey Park, a 16-year-old wunderkind was beginning to find his groove. After starting on guitar at six and switching to bass guitar at nine, Larry Klein’s teacher, Herb Mickman, was schooling him on electric, upright, piano, and jazz harmony, and it was Mickman who suggested they go see the Bill Evans Trio – at the Playboy Club.

“I wasn't even allowed to be there, but somehow he managed to spirit me into the place,” Klein told Bass Player. “You can imagine a 16-year-old kid seeing Bill Evans and Eddie Gomez at the Playboy Club, with Playboy Bunnies walking around. I thought I had died and gone to heaven!”

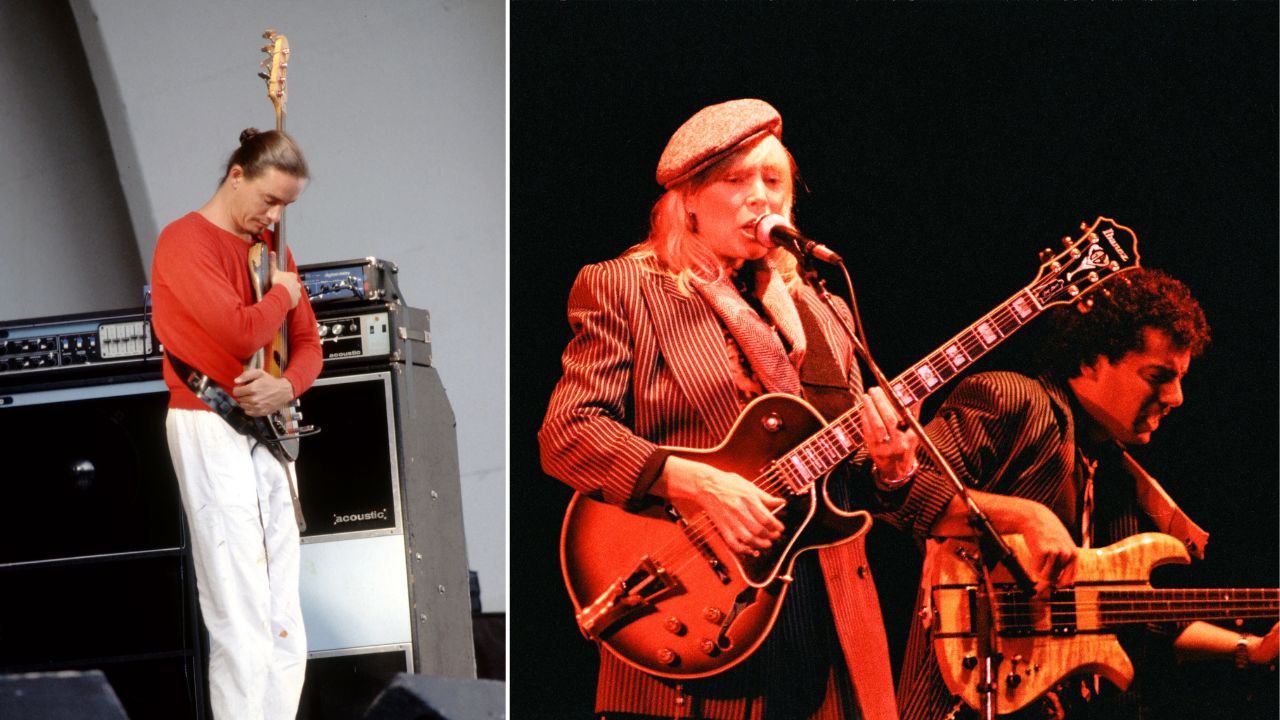

However, Klein's career hadn't even begun. His broad palette and ear for pop allowed him to move smoothly from a promising late-'70s stint as a top-flight jazz sideman to a career as a versatile session ninja with film-scoring skills, capable of creating bass sub-hooks on huge '80s hits, as well as a fresh, contemporary approach to Joni Mitchell's music after her celebrated string of albums featuring Jaco Pastorius.

“Before me, guys like Max Bennett – and even earlier, Stephen Stills – had played bass on her records. Joni was ready to work with someone who played in a way where the bass wasn't down at the bottom of the track. Jaco was her liberator, but she also wanted the bass to play a greater part in holding down the groove.”

Klein developed a reputation for being relaxed, sensitive, and open to new ideas, qualities that certainly endeared him to Mitchell, who first hired him in 1982.

They were married from 1982 to 1994, and Klein played on, produced, or co-produced everything she's done since the '80s, nabbing Grammys for 1995's Turbulent Indigo, 2001's Both Sides Now, Herbie Hancock's 2008 masterwork River: The Joni Letters, and its follow-up, 2011's The Imagine Project.

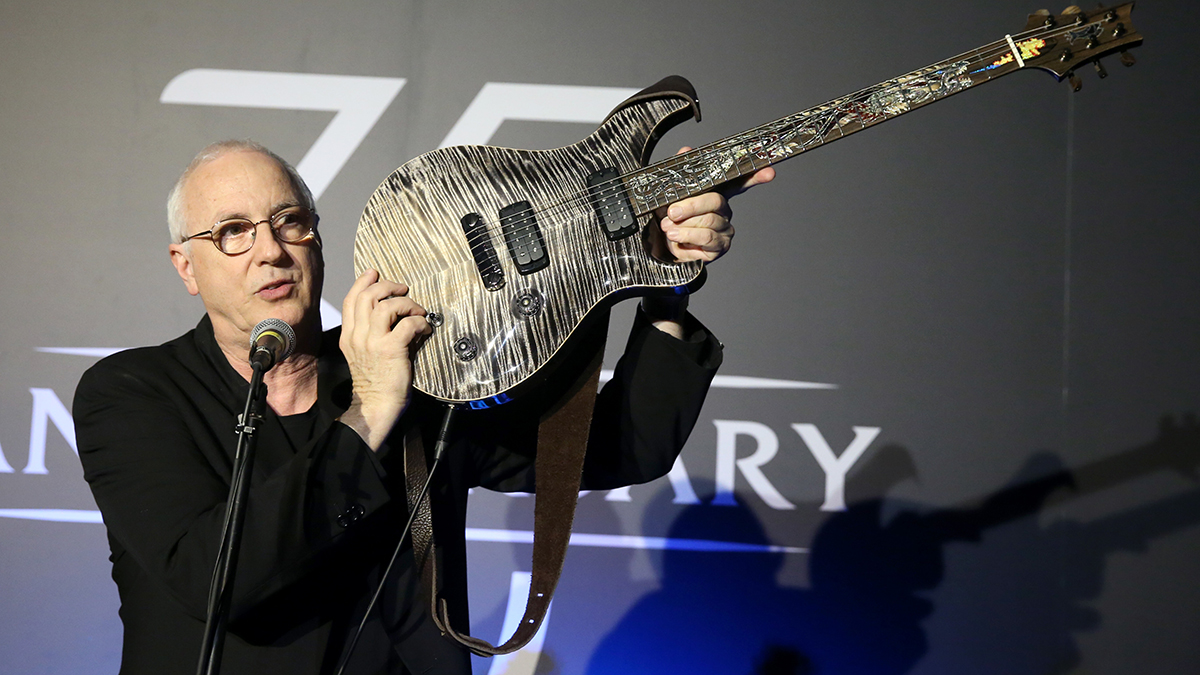

When the mood strikes him, Klein still reaches for a sunburst '62 Jazz Bass, a Gretsch Country Gentleman, or his longtime favorite, a Music Man StingRay 5-string, but producing is what he loves most these days.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in 2014.

You took lessons with Fred Rivera and Herb Mickman, but did you have other teachers?

“Those were my two first teachers. I also took private composition classes with a guy named Wayne Bischoff, a Mr. Holland's Opus-type character, in seventh grade, and I studied classical arco technique with John Schiavo of the L.A. Philharmonic. I was really lucky all my life in finding the right teachers.”

How relevant to your career were those years of studying theory and harmony?

“All the things you absorb, whether it be a Beethoven symphony or a song you hear on the radio – all of it ends up informing your musical instincts. Early on, it may have seemed like all that disparate information had no effect on what I played intuitively, but eventually, it affected how I built basslines and how I saw bass fitting into the design of a given track.

“Everything in our world now is so abbreviated, moving at such an incredibly fast rate, people forget that apprenticeship and studying and focusing on the basic building blocks of playing and writing music are so important. I'm happy to rant on that whenever possible.”

How did your time with Joni Mitchell affect your knowledge of harmony?

“Profoundly. She crafted a sense of harmony for herself by virtue of the tunings she developed, all because she just didn't have the hand strength to finger chords in the usual way. I ended up using those guitar tunings myself to write with, so yes, she strongly influenced my sense of harmony and composition.”

You began working with Joni just after her last album with Jaco. How was that?

“Jaco was functioning pretty much exclusively as a melodic counterpoint to Joni. At the same time, she also didn't want anything that resembled a conventional approach. So l was searching for my own way of approaching both her music and the role of the bass.”

Of all the work you've done together, what stands out?

“Different tracks from all the records pop out from time to time. I like so many things, but Night Ride Home was a wonderful record to make, and I’m really proud of the bass work on there.

“I was asked to contribute to a book about Joni (2013’s Gathered Light: The Poetry of Joni Mitchell's Songs), and I chose to write about Chinese Cafe/Unchained Melody from Wild Things Run Fast. There's something so profound about that track – it makes me cry every time I hear it.”

Did you get to hang with Jaco?

“Yes. As a person, he was such a walking idiosyncrasy. He was so confident and arrogant, but there was a part of his spirit that was innocent and had such a fun edge that I would never hold that against him.”

You walk into a session and hear a track for the first time. What goes through your mind?

“I hear things that tie into the melody, the chord structure, and the way the song is designed. I hear these repetitive things, and I'm sure the reason I hear them is that I've absorbed so many great bass parts by other bass players.”

Do you think bass players are naturally suited to being producers?

“We sit at the intersection of groove, harmony, and melody, and spending years providing the right kind of structure can prepare one to have a vision of how the landscape of a track should be built. But being a producer is a very complex job that changes with every record and every artist.”

Do you usually play on sessions you produce?

“I go back and forth. Sometimes, it's just too many things to do at the same time, so I have some great bass players who are also very patient with me suggesting things. I work with David Piltch quite a bit. I've been a fan of Lee Sklar since I was a kid, and I love using him on records, too.”

Is it true that you had to convince Walter Becker to play bass on his own Circus Money?

“Yes! I produced it and Walter wanted me to play on it, but I felt adamant that he play on it. People don't know – he's serious as a bass player! He's got such a deep groove, and the combination of him and drummer Keith Carlock on that record was just amazing.”

What's your take on creating a long-term career in the music business?

“Joni always used to say that the quickest way to kill your career was to have a hit, and maybe that's true. I certainly like success, but I don't make my decisions based on what I think is going to be a hit.”

What's the most crucial advice he could give after all these years of high-profile collaborations and successes?

“Hold on to your humility, and seek out great teachers. That would be at the top of my list.”