“Bonzo and I were great groovers. People would dance to our music. There aren't many hard rock bands these days that people dance to”: John Paul Jones breaks down his Led Zeppelin bass approach – and what separated his and Jimmy Page's riffs

The all-time bass great discusses his telepathic relationship with John Bonham, early influences, and why Stairway to Heaven's gradual speed-up is part of its magic

Few rock bands carry the mystique of Led Zeppelin. Aside from the sheer primal power of classics like Led Zeppelin IV, one thing that's sustained the band's near-mythical status is that its body of work includes very few live performances.

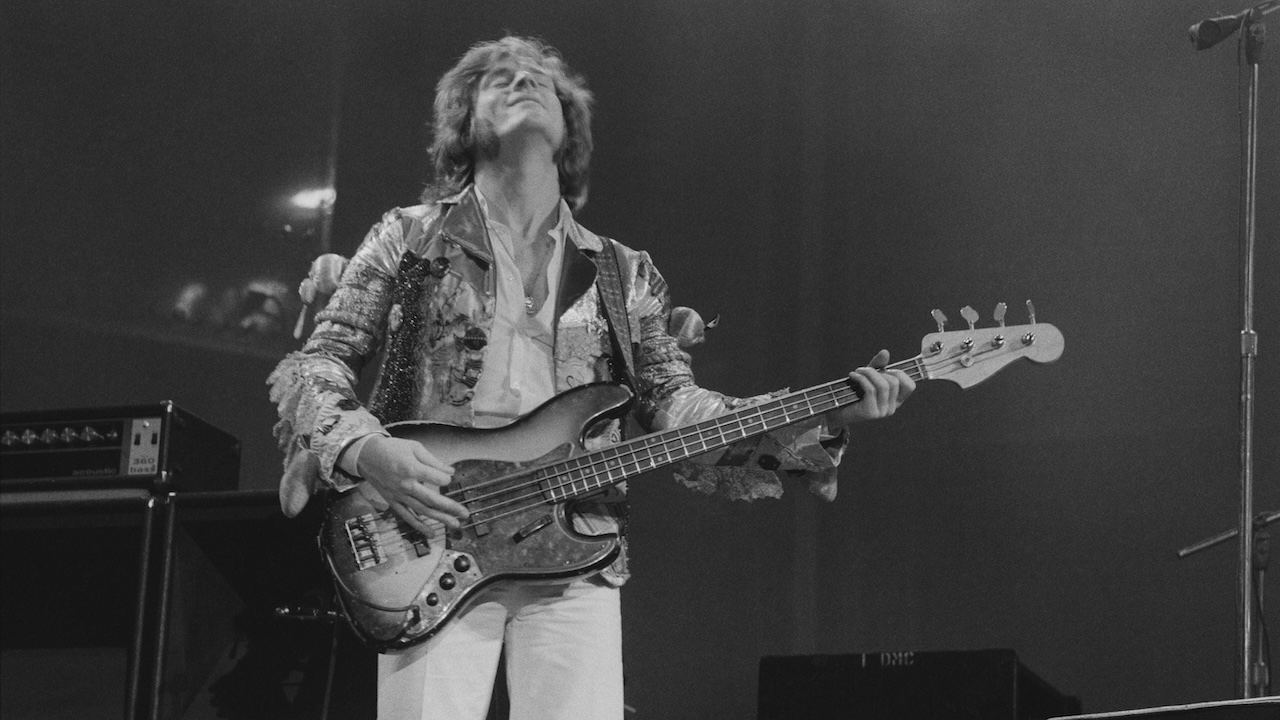

Thankfully, on record, bassist John Paul Jones's ferocity comes across: From his hard-edged Black Dog riffs to the melodicism of Ramble On to his startlingly inventive improvisations on The Lemon Song, Jones inhabited the basslines in Led Zeppelin with the greatest of ease.

“When I was working with John Bonham, the main thing was making sure that my notes and rhythms complemented the drums,” Jones told Bass Player in 2013. “For us, it was all about how good the band sounded, and we always worked to make the other members sound as good as they could.”

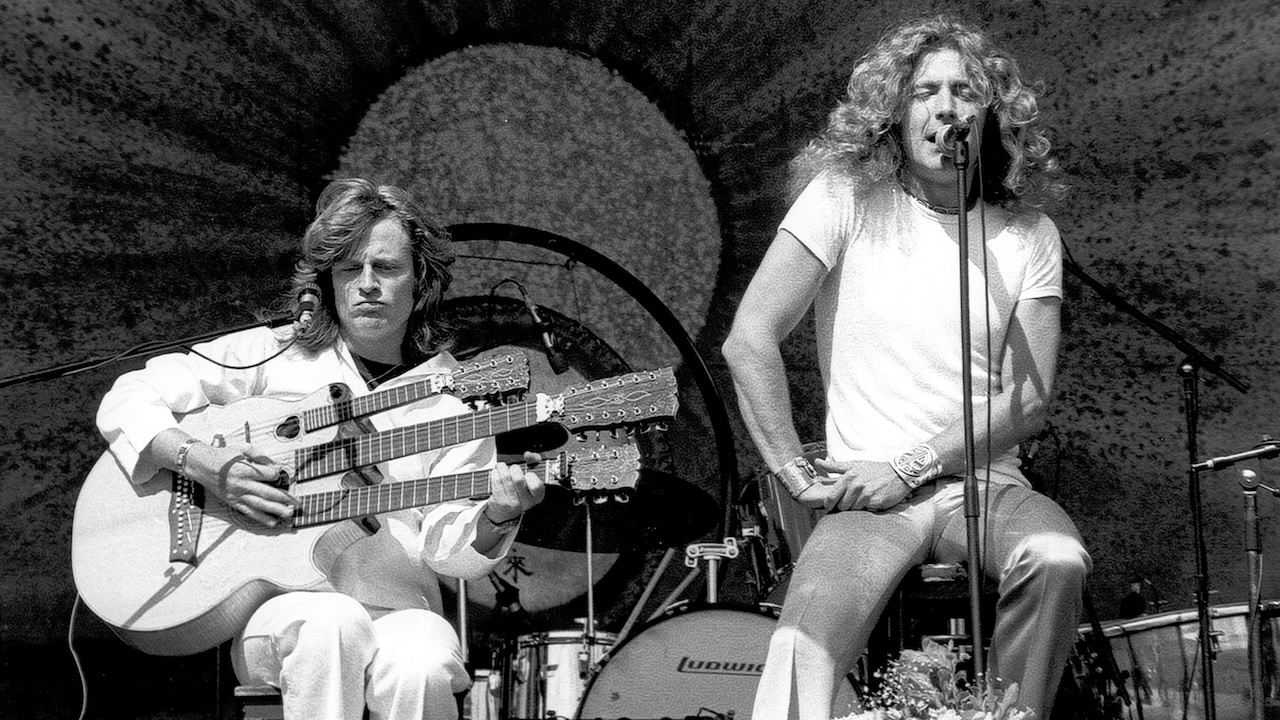

“If Jimmy was soloing on guitar, we'd make sure he had the proper backing to solo over. But it wasn't a plan we'd write out on a piece of paper. It was a total commitment to the band that made it what it was.”

Armed with years of experience as a session bassist and arranger – having worked with the Yardbirds, the Rolling Stones, and Jeff Beck – Jones brought an ear for experimentation to Led Zeppelin, folding keyboards, mandolin, and much more into his band's potent brew of blues, folk, rockabilly, and hard rock.

“My strong roots are from rhythm & blues and soul music, and jazz, but with Led Zeppelin, anyone could go anywhere musically, and we always knew we'd be followed. It was almost like a flock of birds, where one bird flies in a different direction and suddenly the whole flock changes direction.

“Jimmy and Robert had more of the Delta blues and a bit of Chicago blues sound, but I wasn’t afraid of bringing something new into the mix. There was also blues coming through soul music, and blues coming through jazz. So with all of that, we were able to make a unique approach to blues-based music.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Did you ever go through a period when you'd transcribe other players' basslines and analyze what they were doing?

“Not at all. That might work for some people, but not for me. When you listen to a certain kind of music a lot, you begin to think that way – you understand why they play what they play, not just what they're playing, which is the case when you're simply copying something.

“When I started playing bass, I would switch on the radio and just play to it. That's great training. To start, back then, not everything was in exactly the same tuning; there were no electronic tuners, so unless there was a keyboard instrument, tuning on records was fairly arbitrary. So I'd hear something, I might have to retune quickly, and I'd just have to start playing and make sense of it.

“After a while I began to anticipate how sequences were going to go. I grew to know what was going to happen in the music and then be ready for it. The only thing you can't busk to like that is salsa music, because the bass hits the beat before anyone else does – so if you don't know the tune, you're fucked!”

Who were your most important bass influences?

“I had always listened to Duck Dunn, and later, to Motown and James Jamerson, and Willie Weeks. The groove was very important to me and to the band. Bonzo and I were great groovers – we really were. In those days, we'd play concerts and people would dance to our music. There aren't many hard rock bands these days that people dance to.

“I liked the simplicity of soul records in those days. It was just straight down the line, you know – nice phrasing and tasteful, melodic playing, but with a groove you wouldn't believe.”

You were also heavily into jazz. How did that affect your style?

“Charles Mingus was a huge influence – his power, the melodic aspects of his playing, and also his compositional approach appealed to me. I also would listen to Sonny Rollins, Bill Evans, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, and Miles Davis. Miles's arranger, Gil Evans, was another huge influence.

“I like sparse harmonies – just a few notes to suggest quite a large harmonic range. I used that on the Zeppelin song No Quarter.”

It's hard to imagine a lot of metal players today going home and listening to Ornette Coleman records.

“It's their loss if they don't. But that was also true of a lot of bands back then; their music sounded like slower and faster versions of the same song, and I often thought it was because they listen only to one kind of music. But we had this great range of musical influences, and I always said Led Zeppelin was where all of those influences met.”

One of the striking things about Led Zeppelin is how flexible and organic the grooves were.

“Bonzo and I were pretty adept at putting the beat wherever we wanted. A lot of younger musicians don't understand that you can move the beat around against a pulse, but we used to do it all the time and that would change the tune's dynamic. We didn't think about it, though; we'd just do it.

“Sometimes we knew we were doing it, and we'd have fun seeing exactly how far we could lay back – but generally it was instinctive. We'd know there was a song section that needed a bit more urgency, but didn't want to go any faster, so we'd get just get a little more on top of the beat and push it, but without speeding it up.

“Then again, sometimes we would speed up; there's nothing in the rulebook that says thou shalt stay at the same tempo forever.”

“That was a problem with a lot of the programmed drums in the '80s: People would say, ‘Why isn't this getting more exciting?’ Because you're stuck at this tempo! I mean, Stairway to Heaven has a natural acceleration, and it's part of the tune's dynamic. There's nothing wrong with that at all.”

Weren't you largely responsible for the odd-time riffs on songs like The Ocean and The Crunge?

“Page was into the odd-time stuff, too. My riffs tended to be more melodic, and his were more harmonic, I suppose, with jagged chords. I always liked it when odd times were suggested by the melody; if the melody needs to go around another beat, you just stick in the extra beat.

“They used to do that in Delta blues as well. Country blues was rarely 12 bars; if they needed to say another line, it would be 13 bars! It didn't matter, because it was all organic. I prefer it when an odd time is suggested by the melody or rhythm rather than thinking, ‘I should be clever here and put in a 9/8 bar.’ If you do it that way, it often ends up sounding contrived.”

What did you bring to Zeppelin from your career as a studio session player?

“Apart from a fairly wide knowledge of all types of music, the discipline of sessions was really useful – being able to produce music on time, at a certain place, and to turn up for rehearsals. I know that sounds kind of obvious, but you'd be surprised how many bands today just can't make a rehearsal.

“You've got to show up and be dedicated; if you have a rehearsal, you can't stay home and watch TV just because your girlfriend is washing her hair. As a session player you can't be a minute late. You have to be ready to play when the clock strikes the hour, and you've got to be in top form.”

Nick Wells was the Editor of Bass Guitar magazine from 2009 to 2011, before making strides into the world of Artist Relations with Sheldon Dingwall and Dingwall Guitars. He's also the producer of bass-centric documentaries, Walking the Changes and Beneath the Bassline, as well as Production Manager and Artist Liaison for ScottsBassLessons. In his free time, you'll find him jumping around his bedroom to Kool & The Gang while hammering the life out of his P-Bass.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands

![Led Zeppelin - Stairway To Heaven (Live at Earls Court 1975) [Official Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/Ly6ZhQVnVow/maxresdefault.jpg)