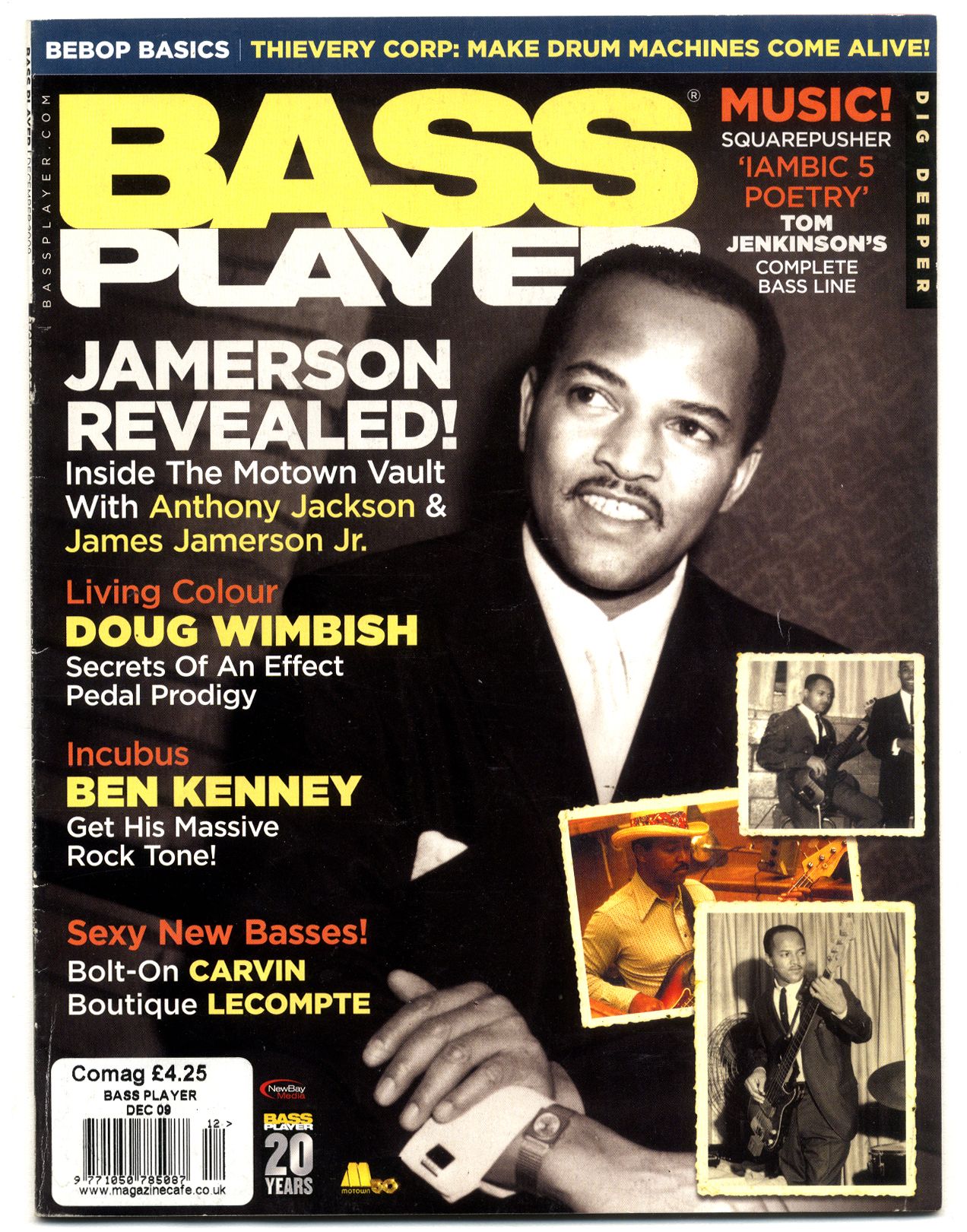

“l’d been listening to Jamerson for some time, but this was staggering”: Inside James Jamerson’s 10 seminal “B-Sides”

Anthony Jackson and James Jamerson Jr reveal the hidden secrets of Motown’s multi-track recordings

The setting is Studio A at Universal Mastering Studios East, in midtown Manhattan. Sitting at opposite ends of the board are Anthony Jackson and James Jamerson Jr., the world's foremost authorities on the style and substance of Motown master James Jamerson.

We were on site to hear tracks that for the most part were B-sides, but are seminal within the Jamerson lexicon. Harry Weinger, VP of A&R for Universal Music's catalog division, with a menu of original session tapes at his fingertips, starts the Supremes' 1968 single, Reflections.

With several instruments turned off in our custom mix, and the bass boosted, Jamerson's bassline is more than just ghost-in-the-machine groove. Standing in the Shadows of Motown author Allan Slutsky described the isolated bass tone as “reeking of bad breath, cheap booze, and body odor.”

Our noses twitch at that very accurate notion while our ears marvel at the warm, round, slightly overdriven sound of the '62 P-Bass captured direct to console.

It was at the suggestion of Slutsky, and with the aid of Weinger and his crack staff, that we decided to visit “the vault” to commemorate the label that launched the legendary career of the father of the bass guitar.

As Jamerson Jr. told Bass Player, “When you say, the Motown sound; you might as well say my dad. Take his bass off all of those tracks and then see what you have.”

Indeed, for countless bassists, whether they knew his name or not, James Jamerson forged the rudimentary template for the instrument. One teen disciple was Anthony Jackson. “He was my greatest teacher. In my formative years on the bass guitar it's astounding to think of how prolific he was; there was a new masterful performance hitting the airwaves every week.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the next four hours we would experience some of Jamerson’s basslines up close, enhanced with the secrets contained in the masters. The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in 2009.

1. Reflections, Diana Ross & The Supremes, 1968

Suitably trippy for the time, this brooding classic rides Jamerson's bouncing groove rife with his singular brand of syncopation and chromaticism.

Anthony Jackson: “This is a class-one, outstanding Jamerson performance. His use of open strings work more as a melodic line than notes that strictly follow the harmony. He knew taking a consonant set of changes and using chromatics for a melody creates great contrast; it moves by quickly and doesn't linger, so there's no sense of wrong-sounding notes.”

James Jamerson Jr: “Given the limited amount of tracks Hitsville had, it's fascinating to hear what instruments they would bounce to one track, like say, bongo, tambourine, and vibes. But they always kept Dad alone on his own track.”

2. The Happening, Diana Ross & The Supremes, 1967

What is essentially a show tune with a near-corny ‘two feel’ co-written by L.A. film composer Frank De Vol becomes a laboratory for Jamerson. His between-the-beat ghost-notes, drops, and climbs single-handedly provide the feel.

Anthony Jackson: “This track really shows Jamerson's first-rank musicianship. The chord changes move around, alluding to different key centers, and there's even some doubling of the melody in what was no doubt a written part. You can hear the effect of the passing tones he uses.

“Most remarkable is that when the tune goes up a half step, from G to Ab, most players would change their part, or at least where they play it. Jamerson doesn't. He uses the same open strings to preserve the integrity of his bassline.”

James Jamerson Jr: “The key here is this track was cut in Los Angeles with another bass player, but then they sent it back to Detroit to re-record the track; they felt it needed my Dad.

“The same thing happened later with the Temptations' Papa Was a Rolling Stone. The producers at Motown in L.A. began to think that way: ‘What would this song sound like if we put Jamerson on it?’”

3. Mutiny, Junior Walker & The All-Stars, 1966

A swinging blues jam, with solos by Walker on alto sax, Victor Thomas on organ, and Jamerson. His intense, upright-founded walking lines build to a breathtaking crescendo by the track's end and his solo is melodic and well paced.

James Jamerson Jr: “When I first put this on the record player at home I was completely blown away. Dad came down the steps with a little smirk and was like, ‘Uh-huh; okay, let's see you play this.’

“Although he rarely talked about or wanted to hear Motown music at home, he would occasionally let me know when he liked something he played on, like What's Going On, Shorty Long's Here Comes the Judge and Houston Person's The Real Thing. He came home with Houston's album one night and said, ‘Your daddy did the thing on here.’”

4. I'm Wondering, Stevie Wonder, 1968

A feel-good track packed with textbook Jamerson licks. Note the numerous open-string and fretted passing tones and the delay in getting to the Ab root in bar 4 (with the Db on the downbeat, momentarily reharmonizing the chord).

Anthony Jackson: “This is a very bold, busy, improvised part loaded with notes outside the chord that are as important as the consonant notes; as such it almost functions as percussion accompaniment – it even sounds more heavily-muted, like he might have had more foam onboard that day.

“Because all the inside and outside notes are played in a repeated pattern the part sounds well thought out and not random. Still, by itself it doesn't really suggest a lot. But in the context of the track it works splendidly.”

James Jamerson Jr: “Just incredible; my Dad is dancing on the bass right there. I had to record that part verbatim for guitarist Al McKay; he wanted it exact – it kicked my butt around the room!”

5. My Whole World Ended (The Moment You Left Me), David Ruffin, 1969

A medium pop tune with a bouncy, double time undercurrent that rides a (Four Tops) Bernadette-like ostinato. A key to the line is the ghosted note on the second 16th of beat two, which Jamerson lays back on. While he repeats this figure through the C-B-F-C chord pattern, dig his in-between fills and climbs.

James Jamerson Jr: “This is one of my favorite tracks for the syncopation Dad has going on and the way he's digging in. He rarely finessed the bass, he would pull on the strings like he was playing his upright. As a result, he could make one note sound like a thousand.

“A lot of the younger bassists think he's playing more notes than he is, and they overcompensate. They haven't learned yet how to come with the power – how to make one note sing.”

6. Too Many Fish In The Sea, The Marvelettes, 1966

Jamerson anchors this classic early-'60s groove with just two notes, waiting patiently to make it his own. Think Marvin Gaye's Ain't That Peculiar with a simpler bassline. The second ending contains a typical pickup he adds, starting at 1:58 and continuing in subtly varied forms through the fade.

Note the C on the last eighth-note of the second ending, an anticipation of the C coming on the downbeat of the next measure, without being tied to it, and held over the bar line.

Anthony Jackson: “I first heard this in someone's car when I was 15 and it really made me sit up and take notice. Everyone plays their same parts throughout, until the end, where only Jamerson stretches out. Although under the radar, the impact of his musical decision, whether dictated to him or not, is as powerful and important as his more standout tracks.”

7. How Long Has That Evening Train Been Gone, Diana Ross & The Supremes, 1966

A laid-back, ultra-funky 16th-note feel that brings to mind the kind of New York City grooves Chuck Rainey and Jerry Jemmott were playing at the time (with Jaco on the horizon).

Anthony Jackson: “l’d been listening to Jamerson for some time, but this was staggering. It became the song I'd work on first and last every day. All the key Jamerson elements are here, dissonance as an effect, use of open strings as both a rhythmic and melodic device, powerful groove, and great sound.

“It has been said that Chopin had a touch of the influence of two other pianists of his time, but for the most part he came out of nowhere, much of his music was not as easily digested and was technically demanding. The same can be said of James Jamerson. His genius is just impossible to trace.”

James Jamerson Jr: “Man, this is one funky track. If he could have kept playing like this I often wonder where else he could have taken it to. There might have been a whole other level after that!”

8. Honey Bee, Diana Ross & The Supremes, 1968

A bright, eighth-note-driven track that's deeper than it seems.

Anthony Jackson: “On the surface it sounds almost like a throwaway track that the Funk Brothers just went in and ran down. But it's classic Jamerson: heavily muted, aggressive, not that many notes, and strong.

“The second chorus opens with James playing a rake so powerful it stands as a peak example of him using that particular technique; it's the E on the D string, down to the B on the A string, to the open E – real fast and twice in a row.”

James Jamerson Jr: “It's one of my favorite Motown tracks; it really moves.”

9. It's Wonderful (To Be Loved By You), Jimmy Ruffin, 1969

A well-written, eighth-note-based pop song that cleverly pivots between C major and C minor.

Anthony Jackson: “I first came across this track many years later on the BBC; the single was only released in the U.K. It's just a great song with a terrific, active Jamerson performance.”

James Jamerson Jr: “This is my first time hearing this song and it is wonderful! I probably haven't heard half of my dad's work, they did so much recording. And there are songs I remember listening to while they were being cut that I've never heard on record or radio. Often, after the take I'd ask Dad who it was for he'd say, 'I don't know, whoever.’”

10. Shoe Leather Expressway, Martha Reeves & The Vandellas, 1969

A funky bass riff and open-voiced chords on acoustic piano make for an offbeat but compelling track. The two-bar phrase is always the same in bar 1, with bar 2 serving as an improvised or fill measure.

Anthony Jackson: “This is a stellar example of Jamerson's use of dynamics, which is the key to making his repetitive bass part breathe. The highly original track also reminds that Motown was a collection of people who knew just how far to push, from Berry Gordy on down.

“Especially the Funk Brothers, who always seemed to find a niche – even if their parts were written – and do their own thing, while maintaining the wishes of the composer, producer, arranger, and artist.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)