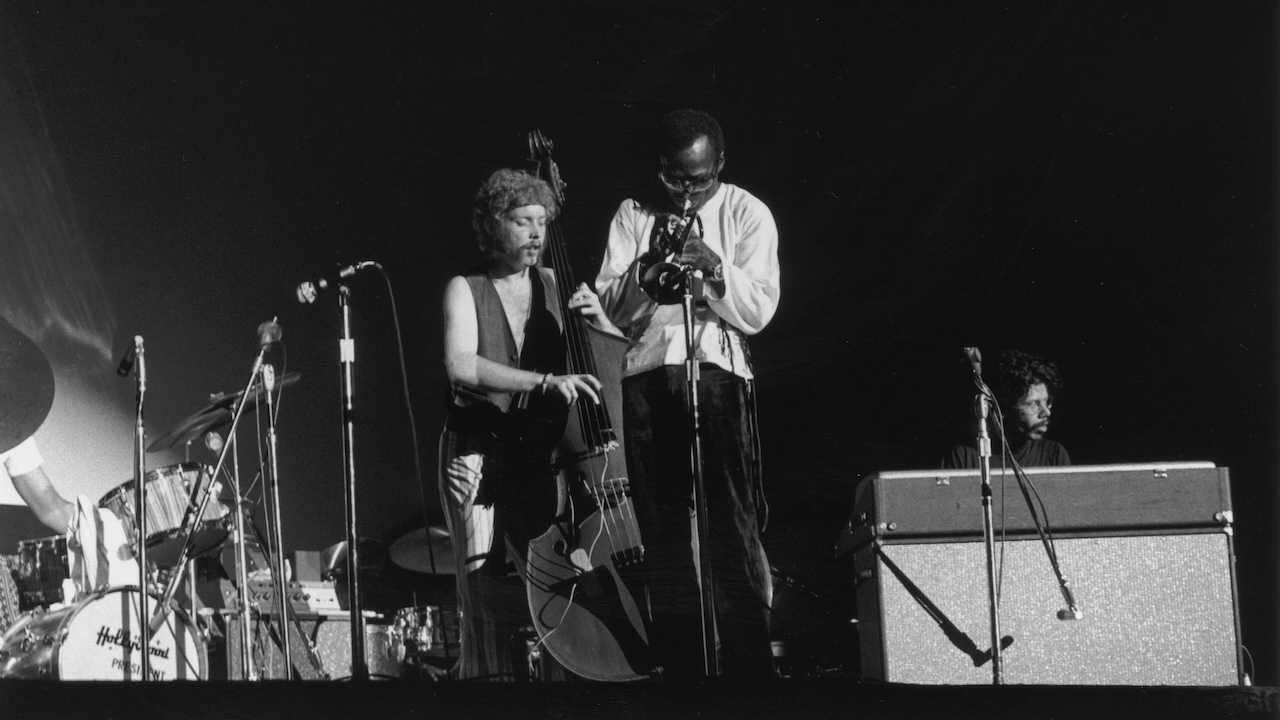

“I sold all my stuff. I even left my car out on the street!” When asked by Miles Davis to move to New York and play some shows, bass great Dave Holland didn’t blink

Dave Holland’s arrival in New York coincided with one of the most transformative periods for Miles Davis and his Lost Quintet

By building on the tradition of great bass-playing composers like Charles Mingus and Oscar Pettiford, while pushing the instrumental envelope as far as any modern great, Dave Holland ranks as a true living legend of jazz.

Born in Wolverhampton, England, he spent his adolescence playing bass guitar in local pop groups. At 17, he heard bassists Ray Brown and Leroy Vinegar for the first time, and it was a watershed moment in his development.

“They blew me away,” Holland told Bass Player. “I bought a cheap plywood upright and started learning lines off all the records I could find.”

As his local star grew, Holland left home for London and found an excellent teacher in London Philharmonic Principal Bassist James Merrit. Recognizing his potential, Merrit recommended him to the Guildhall School of Music.

One evening in 1968, Miles Davis, in London on tour, stopped by Ronnie Scott's jazz club, where he happened upon Holland playing in a piano trio. Liking what he heard, Miles called a few days later and asked him to move to New York. Holland didn't blink. “I sold all my stuff. I even left my car out on the street!”

Holland's arrival in New York coincided with one of Miles' most transformative periods, and it would prove to be a turning point in his career. Over the course of three years Holland played on many of Davis's best regarded albums of the period, including Bitches Brew, In a Silent Way and Live at the Fillmore East.

“The experience with Miles was a chance to see how he developed music: what elements he discarded and what elements he used in a piece, and how he related to the musicians – his way of encouraging you to really look inside yourself to figure out what your creative contributions could be.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in January 2005, following a short tour with Herbie Hancock on piano, Wayne Shorter on saxophone, and Brian Blade on drums.

How was your recent tour with Herbie Hancock?

“That band was interesting because we had only three days of rehearsal. We did five or six hours a day, but we spent most of the time talking. It wasn't always about music, either; we discussed politics, books, imagery, but what it all added up to was an empathy, which I think is crucial.

“I don't think we really saw where the music could go until the first concert. And it sort of stayed that way for the whole tour. It was all the things I love about music, in terms of the human element: people giving and taking and sharing, being willing to take the lead or step back and let somebody else speak.”

What would you say to someone trying to develop a musical vision?

“Sometimes musicians are waiting for some big intuitive leap of creativity where a light is going to go off, but a lot of it is in the trenches. Go to the bass; work some stuff out. Go to the piano; write a song. Try to refine your compositions. Focus on the journeyman aspects of being a musician. I think that helps you make consistent progress in your development.

“I remember reading an interview with Coltrane where he said that if he could play only one new idea every day, then at the end of the year he'd have 365 new ideas. And that would be progress. When I read that, I thought, ‘Yeah – that's what progress is.’ It's not about huge leaps.”

How has your practice regimen changed over the years?

“As a young musician I focused on learning about the basics of music. I was practicing with records and trying to understand how to play a certain feel, or understanding how to create a good bassline and be supportive – learning how to solo and so on. Those are the things I'm still learning.”

“Now, a big part of my practice is about keeping my physical side prepared. It's pretty boring in some ways. Usually the first thing I do is play through all the scales, the 12 major and minor keys and all the arpeggios. Then I have some pizzicato exercises I practice. It's like calisthenics.

“The other part of practicing, which I think becomes more important as you get older and have got the mechanics of music behind you, is mental preparation – the conceptual practice.

“For me, the conceptual preparation deals with playing the keyboard and analyzing aspects of music from that perspective. The keyboard is the central instrument to the music. You can realize the whole orchestra on a piano.”

What non-musical things inspire you?

“One of the first impressions I had when I played with Miles was standing behind him and being amazed by his presence, and his focus. It's something I've seen in great players: the ability to be totally in the moment, totally immersed in the world of what they're creating. It's like a boxer: You've got to be mentally prepared for what you're about to do. And it's not like you've got to meditate.”

“Sometimes it's about sitting around with the other musicians and having some good conversation. But once you hit the stage, it's about being focused on what's happening, where the music is at, where it's going, and where it's coming from using your full emotional resources on bringing the music to bear.”

It sounds like listening is essential to this focus.

“Listening is at least as important as playing. All the great players were great listeners as well. Music is about entering into a communion with the other musicians and being connected – having a dialogue with one another.

“A real important part of a good performance is how connected we are – how much we're able to share in creating the music. When you have that kind of feeling in a band, it gives you freedom. You have trust; you have support.”

Can you point to experiences in your musical past that were essential to your development as a bandleader?

“It goes back a long way. As a young musician, I was watching and trying to learn from the people I worked with. I dug Kenny Wheeler's approach to composition. Chris McGregor, a South African bandleader, had a multi-racial band that ended up in London. Chris’s band was a wonderful mixture of South African styles with Ellington and Cecil Taylor. He was a mentor in some ways, and an inspiration.

“Sometimes a person is inspiring because of their dedication and intensity. Miles had a way of really refining a composition down to its absolute minimal essentials, and discarding everything else. He could do that when he played, too. He had a way of using space and playing the notes that really mattered.

“Working with Anthony Braxton and Sam Rivers was also important. Anthony was inspiring because of his dedication and his commitment to finding his own voice and to being his own person in the music. During that period he encouraged me a lot to do the same thing. He d say to me, ‘Holland, you just got to insist on your music!’ We'd laugh about it, but it was a crucial thing.”

How did you become so fluid in odd meters?

“It's an ongoing process. We come out of a culture that very rarely moves outside 4/4. But if we were Turkish or Greek or Arabic, odd meters would be part of our daily experience. So it's something you have to work on and train yourself to do.

“A lot of my composing comes out of wanting to write a song that is both interesting to play and that will help me develop my ideas about playing.

“You see the same process with Coltrane: he wrote songs that were connected with the concepts that he was developing as a player. The two worlds feed each other. And it's all about one foot in front of the other – learning about yourself, the music, and the possibilities that come out of what you're working on.”

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)