“I used my P-Bass in the studio and my Jazz Bass live, because it projected a little louder”: Originally recorded as a B-side, this riff-driven blues became a Jimi Hendrix classic – and bassist Billy Cox played a pivotal role

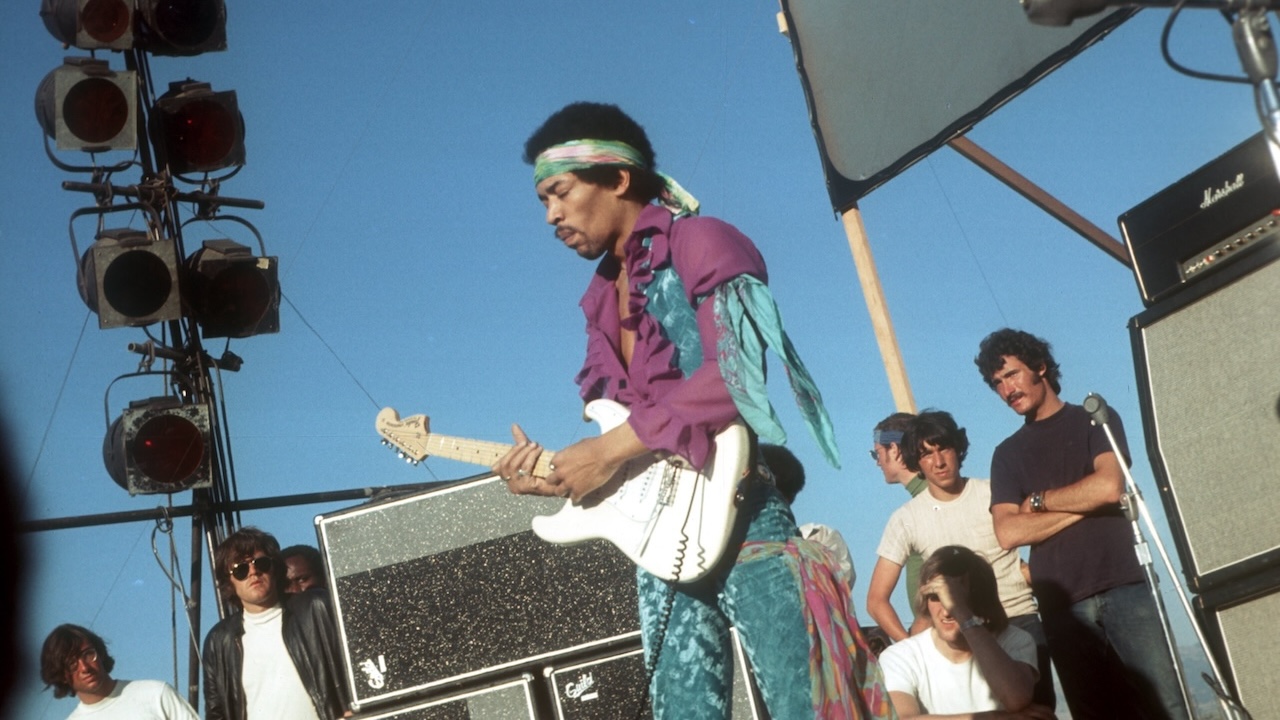

Hendrix named the track after the Olympic White Fender Stratocaster he wielded during his iconic Woodstock set

It’s difficult to imagine, but if Jimi Hendrix were alive today, he'd be pushing 85. But like many other notables who have departed the stage early, the world's archetypal guitar hero is frozen in time in our collective consciousness: forever young, forever groovy.

After dissolving the Jimi Hendrix Experience in 1969 amid a messy tangle of musical frustrations, legal issues, and a soured relationship with bassist Noel Redding, Jimi turned to former bandmate Billy Cox for low-end support.

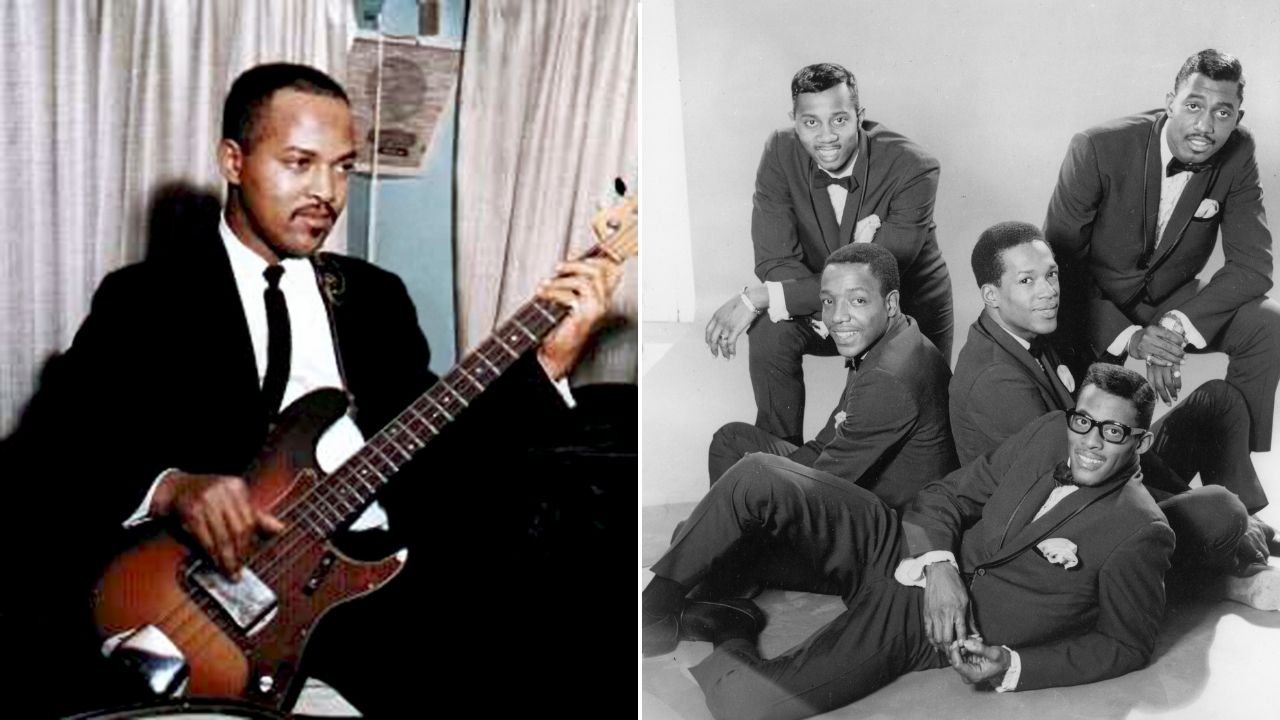

The pair first met in the U.S. Army in 1961 while stationed in Kentucky; they struck up a musical friendship that continued after they left the service, in the form of a Nashville-based R&B outfit called the King Kasuals.

When Hendrix eventually left Nashville to seek his fortune elsewhere, Cox opted to stay put, concentrating on live, studio, and TV work.

In August 1969, Cox appeared with Hendrix at the Woodstock Festival and was part of the trio that cut the live album Band Of Gypsys, which showcased Hendrix's more bluesy, riff-driven R&B sound. Unlike guitarist-turned-bassist Noel Redding, Cox was steeped in the same R&B tradition as Hendrix and was fully hip to the bass styles and trends of the day.

![Jimi Hendrix - Purple Haze - Live Woodstock - 4K Remaster - (Colour Corrected) - [UHD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/liG349SoF_U/maxresdefault.jpg)

Following the breakup of the Band Of Gypsys in early 1970, Hendrix and Cox drafted Experience drummer Mitch Mitchell to replace Buddy Miles and began recording a series of tracks intended for Hendrix's fourth studio album.

Though these songs were made available over the course of three posthumously released albums in the early ‘70s – Hendrix died in September 1970 at age 27 – it wasn't until 1997 that the Hendrix estate assembled the fruits of these final sessions into a single entity titled First Rays of the New Rising Sun.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Izabella, the second song on the album, was originally tracked in January 1970 with Cox on bass and Buddy Miles on drums. It was named after the 1968 Olympic White Stratocaster that Hendrix wielded during his iconic Woodstock set. However, Hendrix was dissatisfied with the recording, and later he added some extra guitar work and had Mitch Mitchell lay down a new drum part.

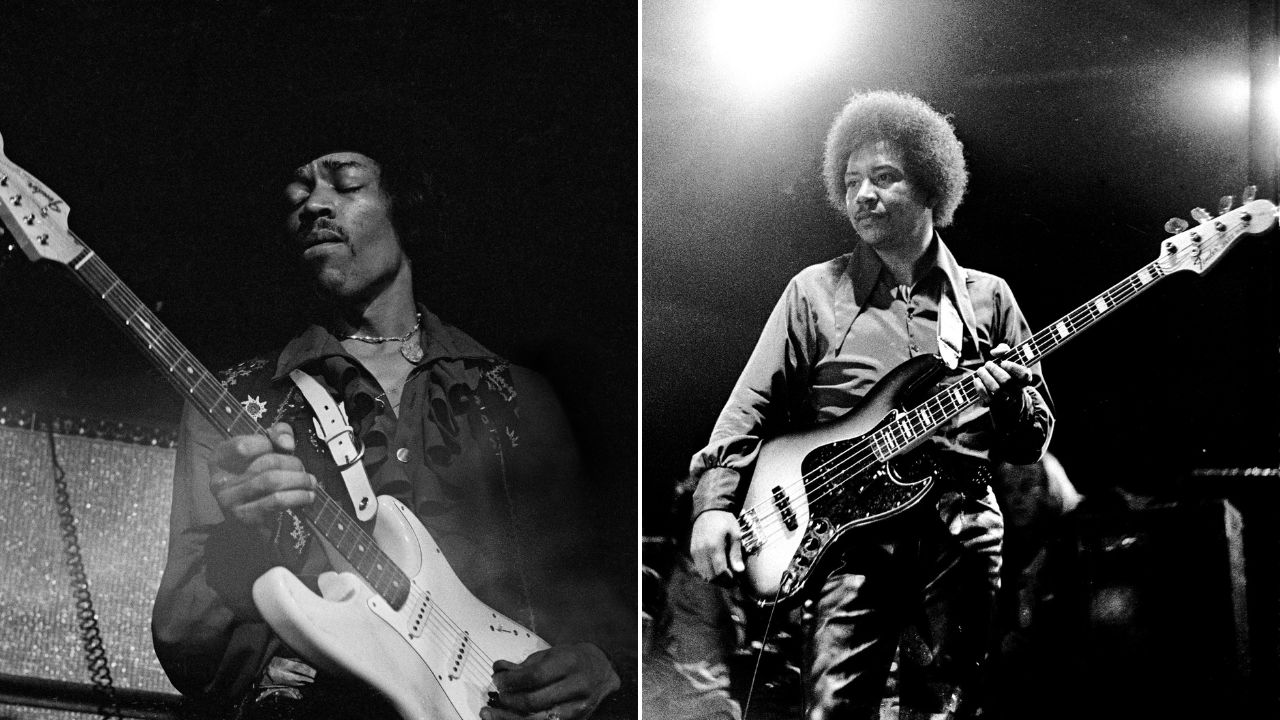

To record his bassline, Cox played fingerstyle and likely used a Fender Precision Bass. In a 2007 interview with Bass Player, he recalled the instruments he played: “I used my P-Bass in the studio and my Jazz Bass live, because it projected a little louder.”

Though Cox's bass playing on Izabella is bereft of needless flash – the track contains no extraneous fills – it's no walk in the park to play. Plucking-hand stamina and careful coordination between the hands are both necessary.

Structurally, the song is a 12-bar blues with one deviation: In the ninth bar of each 12-bar cycle, rather than landing on the dominant 7 chord (in this case, D7 in the home key of G), Hendrix unexpectedly sidesteps down a tone to F before returning in the tenth bar to the anticipated IV chord, or subdominant (C), which is clearly outlined by the syncopated bass/guitar unison line.

After an eight-bar intro, the band gets down to business, introducing the two-bar riff that shapes the song. Cox and Hendrix play this riff throughout the I-IV-I progression in bars 9-16; they subtly alter in bar 17 to suggest a 3-3-2 eighth-note grouping, briefly toss it aside in favor of the syncopated line in bar 18, and pick it up again for the last two bars of the 12-bar cycle.

Harmonically, Izabella is characterized by the sound of the dominant 7#9 chord. Although Hendrix never actually plays this chord per se, the interaction of the multiple guitar tracks and Cox's bassline clearly imply it, transforming the workaday chords of a standard blues into an extended harmony.

This 7#9 flavor is perhaps most apparent where the second guitar track parallels the unison riff over the G7 and C7 tonalities of bars 21-28 and 31-32, emphasizing the major 3rd of each chord, while the riff continues to insist on the sound of the minor 3rds, generating a ballsy harmonic mash in the process.

Also worthy of note is the way Hendrix and Cox tweak the second bar of the main riff throughout this B section, adding in a potent cross-rhythm by grouping the 16ths of beats two through four into units of three.

Coinciding with the guitar solo at 01:10, Cox and Hendrix introduce a new variant: a rising eighth-note arpeggio idea that helps provide contrast between the first part of the song and the return to the main riff at 01:37.

This next section sees the second bar of the main riff altered again to produce a series of offbeat chromatic ascents, which lead into the extended tonic pedal section. Here Cox and Hendrix drive the main riff to its logical conclusion, targeting ever-higher notes at the end of each two-beat phrase (Bb, C, and F, respectively), before spilling down the octave every second bar and repeating the whole idea through to the end of the song.

After 1968's Electric Ladyland, the last of the three seminal studio albums Hendrix completed during his lifetime, his music became more focused, and in many cases, funky. This was due in no small part to the authoritative groove laid down by Cox, who was inducted into the Musician's Hall of Fame in 2009.

And while Noel Redding may garner the lion's share of the low-end glory in the Hendrix annals, Cox nevertheless played a pivotal role in both the beginning and the end of Hendrix's story, neatly bookending the legendary guitarist's short but spectacular career.