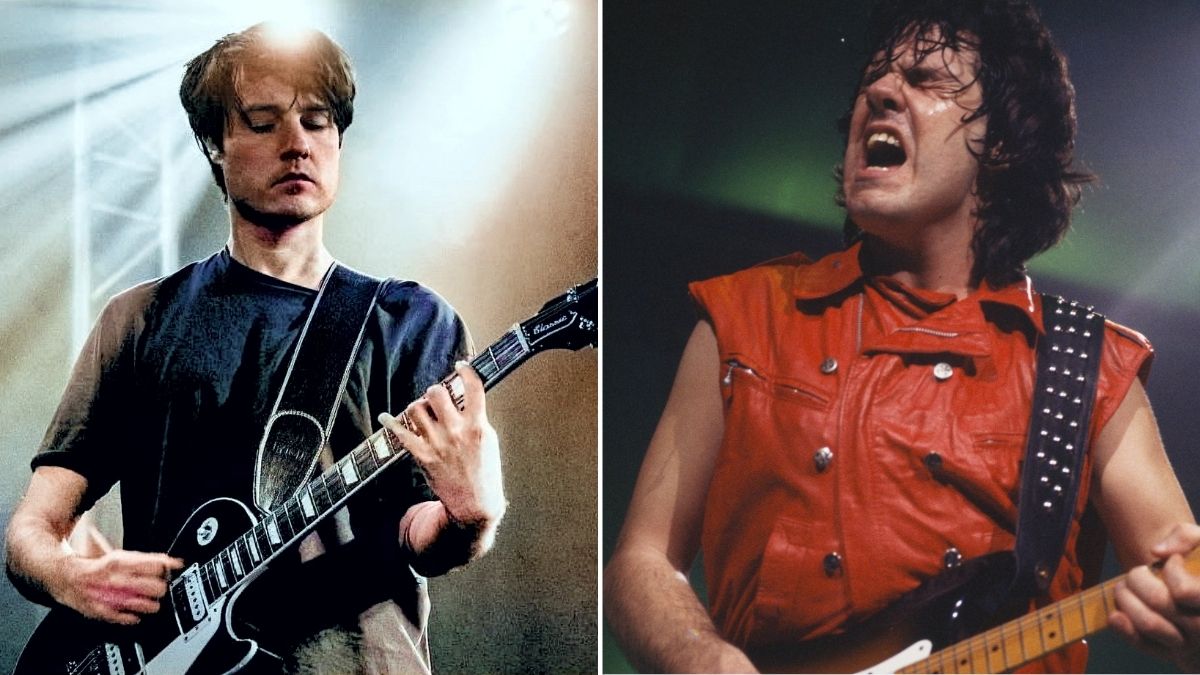

“It dishonors that brand to say, ‘Now we’re King Crimson.’ But we do have the ability to say, ‘Look, this is legitimate – half of the band is onstage here”: Adrian Belew, Steve Vai and Tony Levin on how they made Beat – with Robert Fripp’s blessing

“I’ve had guitar partners in my life,” says Adrian Belew, simultaneously looking backward and forward.

It’s an interesting thought. Given the glorious absurdity and rainbow-like color of his parts – the frenetic samurai-chop rhythms; the effects-heavy solos that can sound like car horns and elephant growls and frazzled dial-up modems, depending on what the song requests – it’s almost shocking that any band could accommodate both his playing and someone else’s.

But then again, he’s built a career out of team-player malleability: supporting Frank Zappa’s comedic rock experiments in the late Seventies, then David Bowie’s artful avant-pop, then the warped post-funk grooves of Talking Heads, then the gleaming New Wave prog of Eighties King Crimson. And that’s just the first few years of a wild and winding career.

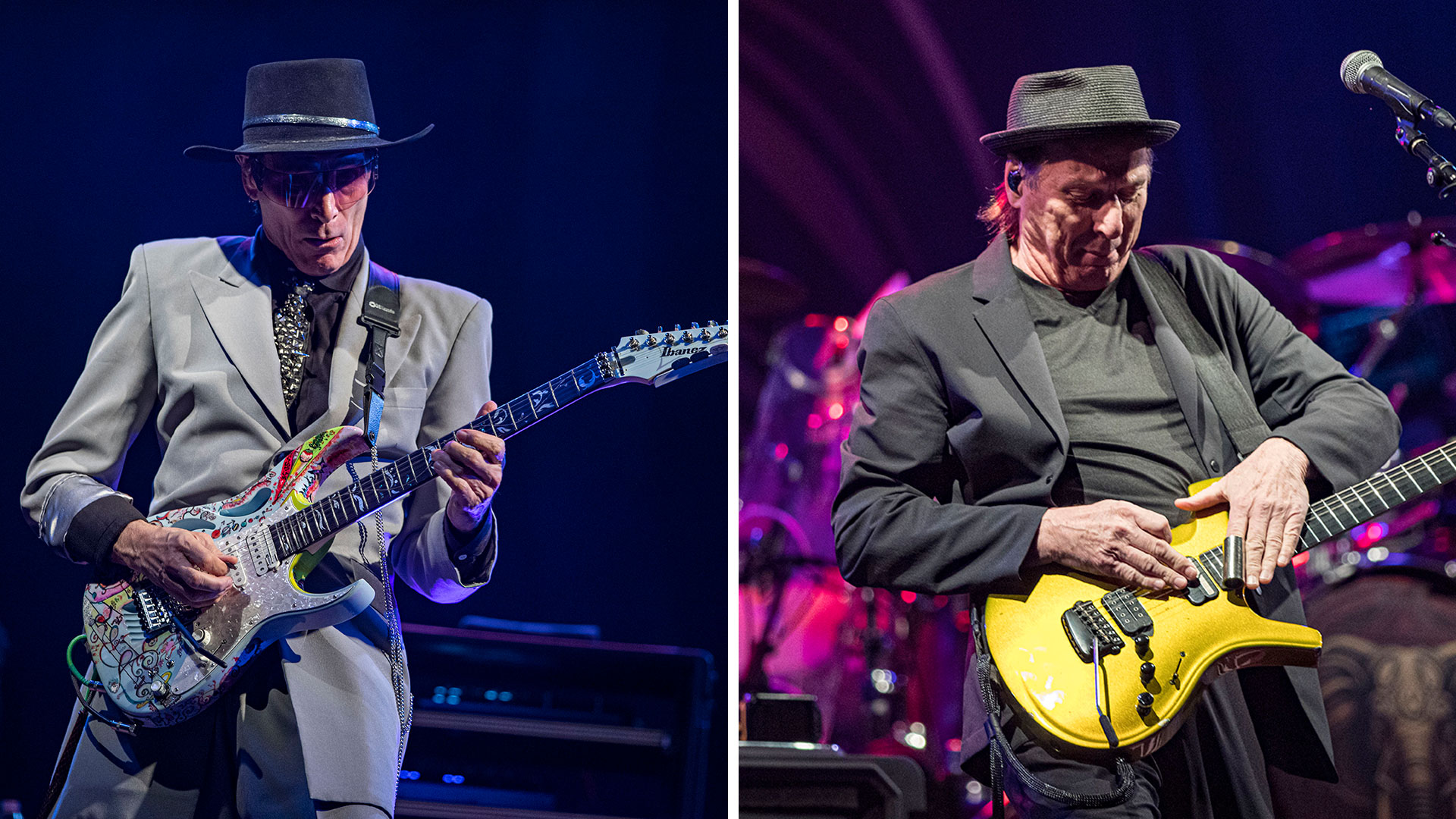

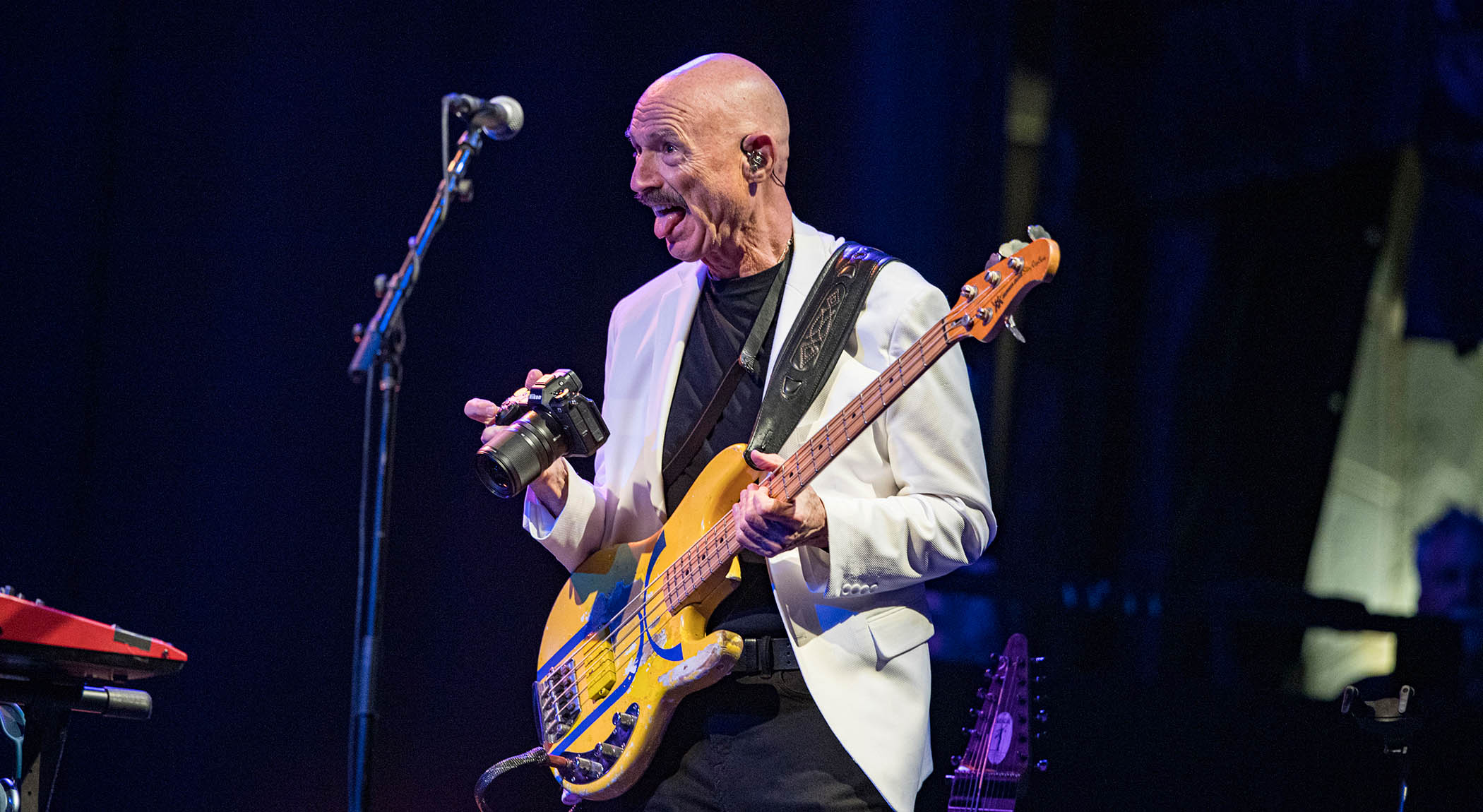

Belew has always had impeccable intuition for knowing how – and when – to partner up. And that’s an obvious prerequisite for his latest venture, Beat: a heavyweight live celebration of the Eighties Crimson catalog co-starring former bandmate Tony Levin (bass guitar), Tool’s Danny Carey (drums) and famed virtuoso Steve Vai (guitar). Which brings us back to those “guitar partners.”

“I won’t count Frank [Zappa] because I just played his parts,” Belew says with a laugh. “I spent years with Rob Fetters developing all the stuff that we did with the Bears. Then Robert [Fripp in King Crimson]. And I think Steve and I will be the same.” It’s a bold statement for a band that, at the time of his quote, hadn’t played one of their scheduled 65 dates.

These are also some enormous shoes to fill: After all, the Eighties Crimson lineup (Belew; Levin; drummer Bill Bruford; and Fripp, the band’s co-founder and lone consistent member since 1968) crafted three of the era’s most distinctive albums – 1981’s Discipline, 1982’s Beat and 1984’s Three of a Perfect Pair – from a tool box of interlocking gamelan guitars, low end often supplied by the extended-range Chapman Stick, acoustic-electronic drumming, Frippertronic ambience and cutting-edge guitar-synthesizers.

In other words, no other band – not even Crimson – has sounded quite like these three albums.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

And no matter how much star power they have at their disposal, Beat have found themselves with a lofty task: honoring the past while also making it feel like the future.

The original impetus for Beat was the 40-year marker of Discipline – a tantalizing jumping-off point in our era of widespread anniversary tours. The year was 2019, and Belew had a radical question: While he hadn’t been a member of King Crimson since 2009 (and wasn’t involved in the final, three-drummer lineups), why not shake off the collective cobwebs and get the old band back together?

It wasn’t going to be easy – after all, Fripp had moved Crimson “from sound to silence” in 2021 and Bruford retired from pro drumming in 2009, 12 years after his final stint in the group. His attempt to conquer the impossible proved fruitful, just not in the way he expected.

First, Fripp politely declined, while offering his blessing for Belew to steer the ship as he pleased. He even (later on in our timeline) suggested the moniker: “[Robert said], ‘I have used the name Discipline for lots of things, even my record label. You and Tony and [King Crimson/Stick Men drummer] Pat Mastelotto have, for 13 years now, have used the name Three of a Perfect Pair for the band camp you do every August. How about you call it Beat?’

“My original thought was that if Robert said yes, maybe Bill would think about it,” he continues. “Once Robert declined, I felt I was honor-bound to make sure Bill didn’t want to do it. I felt it was very unlikely.

“But I’ll tell you something that happened a long time ago to me: I was working with [the Police’s] Stewart Copeland, and he told me had stopped playing drums for 10 years and started doing orchestral things.

“I said, ‘How was it when you came back?’ And he said, ‘It’s just like riding a bike – I could play everything right off the bat.’ So I thought Bill would be able to do the same.

“I love Bill personally. I would love to be hanging around with him again. He’s really a funny and super-smart person. But I did understand [him saying no]. He’s happy where he is and loves being retired. I’m happy for him.”

Two asks, two “no’s” – but it didn’t deflate Belew’s spirits. “I didn’t give up on the idea,” he says, “because I thought it’s worthy to play this music again.” He even held out hope through the pandemic, which derailed any chances of making the 40th anniversary date.

Eventually the stars aligned: Levin, fresh off touring the world with Peter Gabriel, agreed to take part – giving them half of the original lineup. With the other half, they went in a more surprising direction.

Prog-god-on-drums Danny Carey, long an admirer of the Eighties band and even known to sport a Crim T-shirt on occasion (Google it), became the next man up – and with Tool finishing their own massive jaunt, the timing seemed perfect.

(“I’ve known Danny for a long time now, and I know he reveres Bill,” Belew says. “If he wants to be, he’s the closest thing to Bill of any drummer I know of. He’s very invested in – and was very moved by – the three records. He told me many times that those records changed his life, kind of like for my generation how the Beatles did.”)

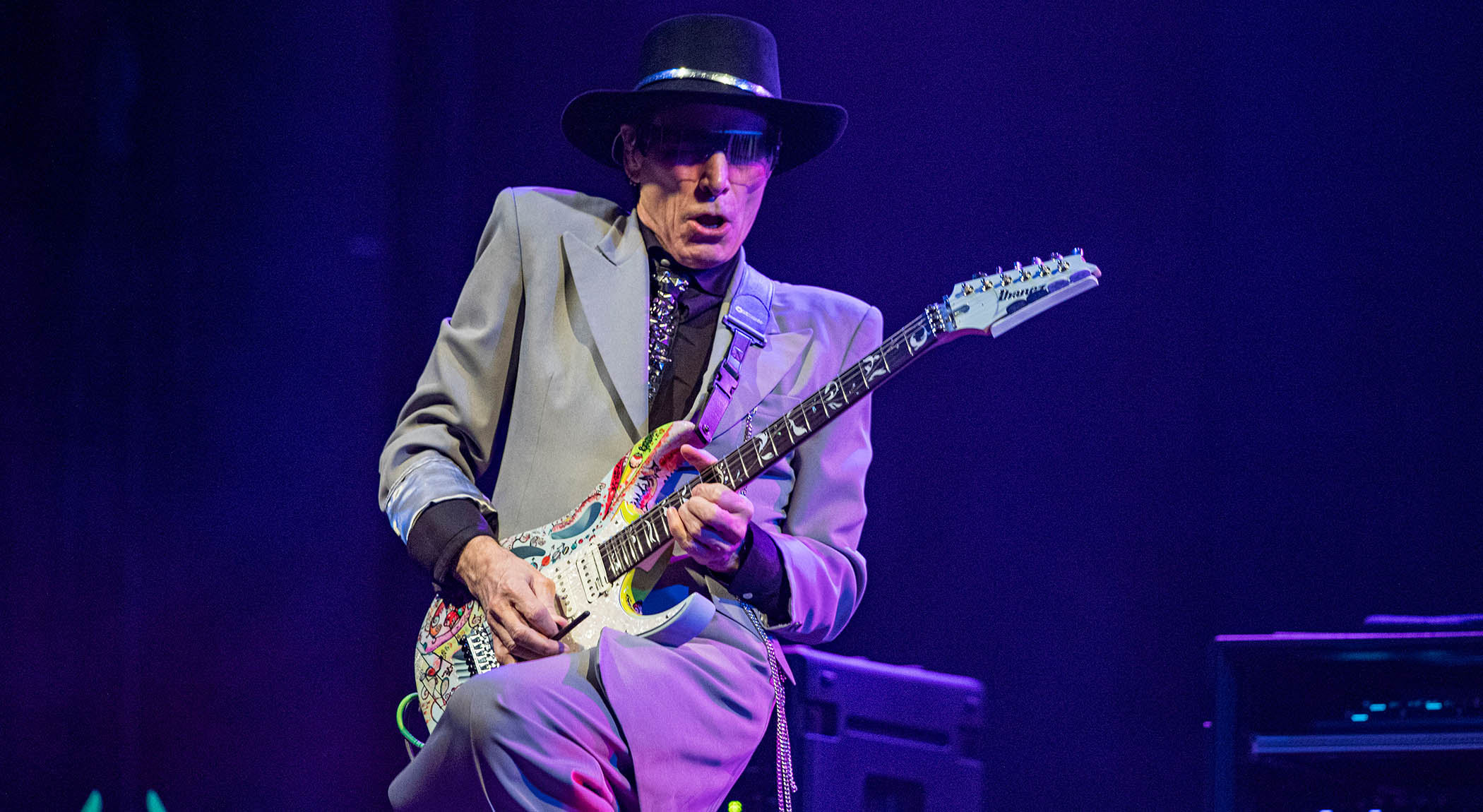

And Vai, who’d previously toured with Fripp as part of G3, had the obvious technical skill to fill the guitar role – but also, just as crucially, a taste for the unexpected, giving Belew an ideal sparring partner. To the latter’s delight, Vai (eventually) leaped at the opportunity – in some ways, it felt weird that these two Zappa alumni hadn’t made it happen sooner.

As an early teenager, Vai was obsessed with the era’s biggest rock bands: Led Zeppelin, Queen, Aerosmith, Kiss. But he later ventured into more progressive music via his friend John Sergio, who turned him on to Jethro Tull, ELP, Yes and early Crim.

“We’d sit in his room and listen to In the Court of the Crimson King. It took a little getting used to for me because it’s so different from something like Led Zeppelin. But I enjoyed it. I was very into high-information music, but I was too young to understand what was really going on.

“It wasn’t until [the 1979 solo album] Exposure that Robert Fripp came onto my radar in a bigger way. I remember when that record came out, and I knew there was something going on in that guy’s head.”

At that point, prog was only “part of a steady musical diet” for Vai – it was the kind of stuff his band couldn’t play because “we just didn’t have the skills for it.” But in the Eighties, “those three monolithic [Crimson] albums really rocked my world.”

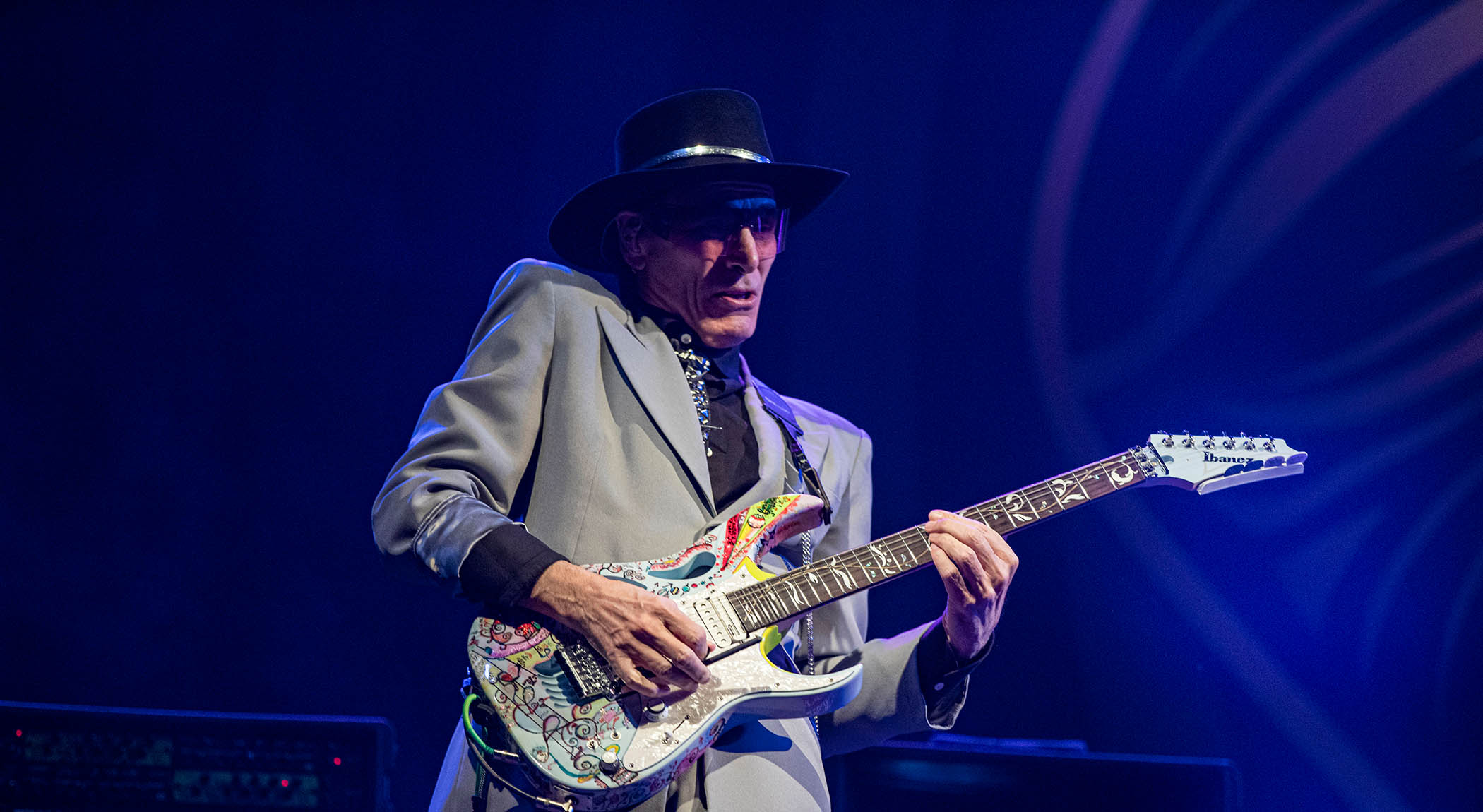

![Beat [L-R]: Tony Levine, Steve Vai, Adrian Belew and Danny Carey](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FCA4Fdi7px4je2hYxfGJCi.jpg)

“At first, you could hear them on the radio,” he says with a laugh. “And in listening to them, I just fell in love with them for the melodies and the seamless complexity. Some things sounded complex, like Larks Tongues in Aspic (Part III) or Discipline, but it was just beautiful. I didn’t lift up the hood at that time to see what was actually going on in the parts.

“My ears could tell there was polymetric stuff – there were juxtaposed eighth notes, and there were formulas for lines that repeat where they come around. I admired how they were doing it so beautifully.”

So when Belew called all those decades later, Vai was eager for the challenge. He just needed the scheduling to make sense.

“When things started opening up, I had a solo record, Inviolate, and I did a full world tour on that,” he says. “We did 194 shows in 51 countries, and Adrian waited patiently. [Laughs]

“Then we spoke, and it started to become more of a serious consideration for everybody. When I heard that Danny Carey was in, obviously with Tony, I just thought, ‘Wow, that is some band.’”

“With Steve, I feel the same kind of chemistry already that I had with Robert,” Belew says. “What I always said with Robert is that we’re like two sides of the same coin – there’s a middle ground that we have in common, but each of us has taken the guitar and our approach in a completely different direction.

“It was pretty easy with Robert because I knew, ‘If I’m gonna do this, he’s gonna do that’ and vice versa. We complemented each other. There’s a lot of being together, sitting together, playing together, talking – the chemistry comes over time, but I automatically feel it now with Steve.”

The Vai/Belew pairing, indeed, seems perfect. With another fret-gymnast on hand, the latter can sing without carrying so much of the guitar burden – and not be forced to rely on looping those interwoven parts himself, as he often does for his solo runs and with his rock-solid Power Trio.

“[Vai] can do his own thing, and he’s got stuff he can do that I wouldn’t even attempt,” Belew says. “Then there are my specialties that I do, and I’ve got the job of being the frontman and singer too. So I can rely on him doing things when I’m not available. [Laughs]

“In the other bands I’ve had in the recent past, it’s mostly been by myself, and I do looping and things. I really like that, but with the King Crimson material, it’s pretty laid out – here it is, and you need to play this much of it perfectly in sync.

“But there’s also a great deal of music in there that you can kinda take and make it your own. And that’s what I’m hoping all of us will do – especially Steve and Danny. We’re not trying to be a cover band. We’re not aiming for that at all. We’re honoring the music, and you can do that in multiple ways.

“Some of this stuff will have to be played as-is – more of the songs, I think. But some of the instrumental stuff, I think me and Steve can fly together or in opposite directions or do whatever we choose.”

That versatility – and that supergroup-level of marquee talent – makes Beat feel like a brand-new venture. But when you survey the lineups of so many long-running prog bands (Yes, for example, now have zero original members), it’s interesting that they didn’t lobby for the King Crimson banner.

“I don’t think I even thought about trying to [use the name],” Belew says. “I know Robert very, very well, and he thinks of King Crimson as being his, and rightly so. And it took me years to realize that, no, it truly is not King Crimson without Robert involved.

“If you think about all of the things he brought to the picture in terms of his leadership and his vision, along with what he added musically with the soundscapes and the fast picking and the gamelan guitar and all the explosive solo sounds… He’s such a big part of it. I wouldn’t even attempt to do that.

“I would think it dishonors that brand a little bit to say, ‘Now we’re King Crimson.’ But we have the ability to say, ‘Look, this is legitimate because half of the band is onstage here.’”

Levin doesn’t even allow himself to ponder labels. “First of all, I don’t think about what King Crimson is, even when I’m in King Crimson,” he says, smiling widely. “I leave that to other people. In the last incarnation of King Crimson, I had to face a new challenge for me, even though I’ve played in a lot of situations.

“When we played the classic material from the Seventies, before I was in the band, it was a top priority to stay true to what’s special about the wonderful John Wetton bass parts, for example. I had the challenge of loving those iconic parts but trying to make them my own.”

“What there wasn’t much of in that incarnation was bass parts that I had written,” he adds. “In this case [with Beat], we’re gonna hit that in spades, and that’s a related challenge but different. There are a few songs where every note has to be what it is – where if I play one note different the whole band might fall apart.

“But mostly, I feel if it’s a good piece of music, there’s room to grow and see where it goes live. In the case of the Beat tour, I’ll be reacting strongly to not only what Adrian plays, but also what Steve plays and what Danny plays. It’s kind of a triple challenge, and I like challenges.

“In a way, it’ll be Crimson-like in that I’ll be able to further refine my part, even on the old pieces where it was pretty darn good but could be better. I’m fine with anything, but if things get changed, that’s great with me. And with Danny, I know they’ll get changed. He’s not gonna literally play the exact drum parts, and that’s why I’m excited about the tour. I’m like a fan – I’m looking forward to going along for the ride.”

It will be fascinating to see Carey – perhaps the most accomplished prog-metal drummer in history, a polyrhythm master who plays with the thunder of 10 men – put his own spin on the Crimson songbook, from melodic staples like Frame by Frame and Three of a Perfect Pair to elliptical instrumentals like “Discipline.” (During our conversation, Belew was reluctant to spoil the set list surprises, though he did share my enthusiasm for dusting off the funky Beat deep cut “Sartori in Tangier.”)

Whatever Carey brings, it will be worthy. And he’ll also offer, personality-wise, lightness and warmth – qualities Belew recognized back when Tool brought along King Crimson, one of their major inspirations, as tour openers in 2001.

“I thought the whole thing was special in the sense that they said to their audience, ‘Here. This is what we like, and this is what helped us get where we are,’” Belew says. “When does a band do that for another band? [Laughs] It really endeared me to them, and their shows were phenomenal. I do remember one crazy thing; we played in Red Rocks, a very amazing 10,000-seat place – and you don’t get to play there very often, and you’ve got to be a pretty big band.

“King Crimson on its own couldn’t have played there, but they allowed us to be their opener. We played, and there were maybe 1,500 people there. That was fine – these were Tool fans who came to see what all the excitement was about.

“Then we stopped and the place filled up to 10,000. I was standing at the mixing board, looking around at all of these people, thinking, ‘They have no idea what I’ve done.’ [Laughs] I really felt like, ‘Wow, I’ve got to start over!’ ” [Laughs]

With Beat, Carey is giving his props in a more overt way – but again, nothing about this project seems nostalgic or rote. For one, these guys are putting in the hours to make this thing electric: mixing new and vintage gear (Belew mentions both the Roland Jazz Chorus amp and a bonkers Electro-Harmonix Echoflanger pedal), workshopping tons of songs, and, for the newbies at least, figuring out where to pay homage and where to forge ahead.

“Robert has been so generous and so kind and so communicative,” Vai says. “We’ve been going back and forth on all sorts of interesting things. For instance, I said, ‘In Neurotica, in various versions… sometimes you’re doing this, and sometimes you’re doing that. Could you tell me a little about that?’ Boy, he was just so generous and explained it all, but at the end he said, ‘Don’t do any of it. Do you!’ It’s just marvelous.”

“We do email, and we met up several times,” he adds. “There were a couple of days I went out to see him. I just love his musical mind so much – and his whole self, his whole personality. We’re both a little quirky. He just did something so beautiful the other day; we were talking about the splendors of the altered scale, and he sent me this beautiful one that he uses.

“Altered scales allow you to do certain things with chords that conventional scales don’t. He was explaining his approach to these very Fripp-type altered chords with all of the theory behind it.

“The man is a wizard. I have my own private little video from Robert giving me a demonstration. Those are the chords I’m going to use in Neurotica, but I’m going to smooth them in a very Vai-istic way. He really wants to see this music being reimagined, blendered and done with joy. And who wouldn’t? What musician wouldn’t?”

And though he won’t be on stage, Fripp’s enthusiasm – and even active assistance – is essential to this whole endeavor.

People can believe whatever they want to believe, but Robert and I have been close friends for 33 years

Adrian Belew

“It means a lot,” Belew says. “I don’t know how it got started years ago, but there were rumors that me and Robert didn’t get along and this and that. I could go back, point by point, and dispute everything that was said. People can believe whatever they want to believe, but Robert and I have been close friends for 33 years. He used to live in my house. One year he lived here 109 days. I keep a calendar of everything that happens every day. The closeness between the two of us is something that goes beyond what most people experience.”

Meanwhile, Belew says his newest “guitar partner” just wants to approach the gig “honorably.”

“One of the first things Steve said to me was, ‘Is Robert good with this? I just want to be able to honor Robert’s playing.’ Because it means a lot to him. When you have people with that kind of attitude, great things can happen.”

Ryan Reed is a Knoxville, Tennessee-based writer, editor, musician, record collector, prog junkie, and former college professor. In addition to Guitar World, he's a contributor at SPIN (current title: senior editor), Rolling Stone, TIDAL, Relix, Ultimate Classic Rock, Revolver, and many other outlets. He's also the author of 2018’s Fleetwood Mac FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About the Iconic Rock Survivors.

“We hadn’t really rehearsed. As we were walking to the stage, he said, ‘Hang on, boys!’ And he went in the corner and vomited”: Assembled on 24 hours' notice, this John Lennon-led, motley crew supergroup marked the beginning of the end of the Beatles

“I pushed myself to down-pick faster and make the riffs more aggressive. Maybe it’s the old man in me struggling to feel young and fighting back against aging”: How Killswitch Engage went to thrash metal bootcamp to deliver their face-ripping return