AC/DC: Young Lust

On Ballbreaker, AC/DC’s Angus and Malcolm Young demonstrate yet again that they are randy as a pair of billygoats, and ready to rock.

Like Divine Brown (Hugh Grant’s hooker consort), AC/DC are a guilty pleasure best enjoyed in the car. College professors, doctors, men and women from the finest families…they’ve all done it. At some time or another, all have experienced the thrill of cranking the car stereo to 10, mashing down the accelerator and bellowing along to the choruses of “Highway to Hell” or “You Shook Me All Night Long.” AC/DC have the power to bring out the randy, socially irresponsible adolescent male in everyone, regardless of age, gender or IQ. (Actually randy, socially irresponsible adolescent males think they’re pretty cool too.)

AC/DC are that which no one can really argue with: a fucking great rock band. Their new record is called Ballbreaker. (What else?) The first AC/DC studio album in five years, it’s a nasty piece of work. With the band’s original drummer, Phil Rudd, back on the throne, the grooves have never been drier or grittier. Angus Young’s lead guitar work is remarkably concise and prickly, chafing like a tight dog collar made of cracked leather and dirty blues barbs. His older brother Malcolm— AC/DC’s “secret weapon”—kicks in with walls of rhythm and guitar hooks bigger than Bo Diddley’s Cadillac. And, as song titles like “Hard As a Rock,” “Cover You in Oil,” “Caught with Your Pants Down” and “Whiskey on the Rocks” should make clear, AC/DC have hardly retooled their lyrical stance for the politically correct Nineties.

“People can go out and hear R.E.M. if they want deep lyrics,” smirks Malcolm Young. “But at the end of the night, they want to go home and get fucked. And that’s where AC/DC comes into it. I think that’s what’s kept us around so long. Because people want more fuckin’.”

Only the most hopeless prude could be offended by AC/DC. They do “bad taste” with such panache it amounts to sheer poetry. They are the Coleridges of cock rock. The Tennysons of testosterone. The Shakespeares of salacious, schoolboy smut.

“Salacious…I like that word.” AC/DC vocalist Brian Johnson leers approvingly at my description of the band’s lyrics. Although he sings said lyrics in the tonal range of a sadistically trussed magpie, Johnson’s speaking voice is deep and thick with the sooty vowels of working-class Northern England. Johnson also approves of the acoustics in the cavernous corporate conference room that Time Warner’s New York headquarters has kindly allotted for my encounter with AC/DC. The pseudo-industrial faux-marble walls make the singer’s whiskey-besotted, cutthroat croak of a voice sound truly ominous.

“Aye, this is a greeat ruhom for a bad temper. It’s like the headmaster’s room when you were at school. That’s why they never had wallpaper. So the sound would carry when he’d fookin’ bollock ya.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Curled into an ugly chrome chair, way down at the other end of the ovoid conference table, Angus Young’s compact frame convulses with laughter. It’s the first sign of life AC/DC’s lead guitarist has shown this morning. Brian brings out the mischief in Angus. At most other times when he’s not onstage, AC/DC’s rampaging hellion schoolboy is a quiet man—one who tends to hide behind a perpetual curtain of cigarette smoke, an expressive repertoire of shrugs and winces and a steady stream of Aussie wisecracks. Though he’s legendarily short—under five feet—Angus is elegantly proportioned, with slender, graceful hands.

“We wanted more of a tough sound than we’ve had in the past,” says Angus of Ballbreaker’s bone-dry sound and stark, stripped down arrangements. “With guitars, we wanted to hear the plectrum hit the strings. We didn’t want all the compression and the clipping and the digital sheen.”

Malcolm concurs, crediting producer Rick Rubin with letting the band have their way with the record, rather than urging them to “pretty it up” the way another producer might have: “We just wanted to get back to the old feel of the rhythm. The feel dominated this time. And really the best feels are the simplest, I guess.”

Not that the album was born easily. AC/DC spent months foundering in a New York recording studio before moving out to L.A.’s Ocean Way studios and finding their groove. With characteristic AC/DC luck, they arrived in L.A. right after the big earthquake.

Angus recalls: “My brother phoned up the management office and said, ‘Is Ang on his way to L.A. yet? You’d better stop him. There isn’t an L.A. at the moment.’ ”

There’s something genuinely touching in the way the Young brothers look out for each other. Rock and roll brothers are supposed to fight all the time—like the Kinks’ Ray and Dave Davies or Oasis’ Liam and Noel Gallagher. But AC/DC are fueled by a kinder fraternal dynamic—a yin/yang thing. Angus is the more intuitive brother while Malcolm is more analytical. Angus is the more public brother—AC/DC’s lead guitarist and wearer of the celebrated Schoolboy Suit. But Malcolm is generally held to be the brains behind the operation—the man who stands at the rear and keeps AC/DC’s bruising juggernaut barreling relentlessly down the highway to Hell. Of course, it’s hard to prove generalizations like these. Get either of the brothers alone and all he wants to do is praise the other.

“I think Malcolm underestimates his own talents as a guitar player,” says Angus. “You see someone like Hendrix play and you think, He makes the difficult look simple. That’s the magic of it. And Malcolm’s like that. You pick up his guitar and try to do what he does and you’re in amazement. He’s got an incredible ear, too. He can zero in on things in the studio—pick out a frequency where two notes collide. At first you think, He’s talking shit; there’s nothing there. But you listen back a week later and go, Fuck, those two notes are canceling out there.”

For his part, elder brother Malcolm tends to downplay his role in fine-tuning Angus’ guitar sounds in the studio: “Angus knows when it’s right. He does it himself, really. He maybe needs a bit of support here and there. But I’m the same. If it takes a long time and a bit of a struggle to get your sound, you can lose your perspective. If I’m in the studio, I can run over and tweak his amp for him if I seem a bit frustrated. But other than that, he can get what he wants. He plays the instrument. He knows what he’s doing. If he didn’t, he wouldn’t be up there.”

Malcolm doesn’t do many interviews, but he’s consented to talk to Guitar World. Reputed to be painfully shy, he turns out to be anything but—a cheerful, chummy voice phoning in from a remote locale. Meanwhile, back at the Time Warner conference room, Angus, Brian and I have discovered that the ugly chrome chairs make pretty good go-karts and that the faux-modern power conference table makes a damned convenient center meridian for a racetrack. But finally the boys are convinced to behave and we all settle down to examine both the myth and the reality of the rock and roll institution known as AC/DC.

GUITAR WORLD What do you make of the fact that the young alternative band Veruca Salt named their debut album American Thighs—a quote from AC/DC’s “You Shook Me”?

MALCOLM YOUNG Is that a girl band?

GW It’s two girls, two guys…

MALCOLM Ah, two girls, two guys…

GW Nice-looking girls, at that.

MALCOLM [approvingly] Yeah. Well, if that’s what they… “American Thighs.” Hmmm, great. I haven’t heard their stuff, but anything like that is always a compliment to the band. Although if Barry Manilow got up and did an AC/DC song, that might be a different story. But it’s nice to know that, after 20 years, there are young bands who are aware of us.

ANGUS YOUNG Of course it’s a compliment. And I like American thighs, too. If you look at it, America has dominated the world market for very good thighs. I grew up in admiration of America. You’d pick up a comic book and in the back they’d be selling all these things that I always thought of as really American—like X-ray glasses.

GW X-ray specs! The ads promised you could see through ladies’ dresses.

ANGUS I sent away for them. But I never got ’em.

GW And you still like America—even after that?

ANGUS I love it. And believe you me, America is the land of rock and roll. It started here. Whenever I come here I’m in amazement.

GW Where does the salacious humor in AC/DC’s lyrics come from?

MALCOLM From the whole band, really. That is the band! Your tour bus talk and things—it’s all about that. All the boys, you know? After the night in the club, it’s always the same thing, you know, you talk about… filth. [Malcolm pronounces this word ‘fiwth’] All the jokes and the laughs. It’s easy to be inspired to write lyrics for this band.

ANGUS I think it’s a bit like stand-up comedy. Any guy can get onstage and say “fuck.” But I always think the really funny guys are the ones who can get onstage and not use one dirty word, and yet you think they have. You think it’s a blue joke, but it’s not. That, to me, is clever. And that’s what we try to do with our lyrics.

GW Where did you get the idea to do a song called “Cover You in Oil”?

ANGUS Well, I always liked that double-meaning thing. And I do like to do a bit of painting when I get some free time. I just thought it would be a good play on words. It does sound a bit blatant. When you say “cover you in oil” people think, “Oh, we know what he means.” A lot of times on AC/DC records, it really doesn’t matter what we’re saying. People think the worst just because of who’s saying it. They say, “Uh, oh, these guys are out to cover everyone in hot oil. It’s gonna be Sodom and Gomorrah!”

GW But really the guy in the song wants to paint a picture of the girl—an oil painting. That’s what you’re saying?

ANGUS Well…a bit of that. But as soon as somebody hears something like that, they conjure up all these other images. [pause] If you’re lucky, maybe they’ll even buy the record. [laughs]

GW I had no idea that was a song about fine art.

MALCOLM Neither did I! One of our artistic pieces.

GW Who wrote the line, “I’ll make her wet, I’ll make her mine”?

MALCOLM Now that’s Angus. You’re trying to find out who the deviant is, aren’t you?

GW I just really admire some of your lyrics. You could get a roomful of the best poets and rock critics and they could never come up with some of those lines.

MALCOLM Or even a roomful of psychiatrists.

GW So, Brian, what’s it like when these guys hand you some racy lyric to sing?

BRIAN JOHNSON Oh, they’re great fun to sing and all. You can get the jokes straight away. The words make you want to laugh and giggle, and sometimes you can hear me doing that at the end of a song, as it fades out. Their lyrics are like a little script when you look at them on paper. Malcolm would come into the room when I was singing and he’d create a little scenario—just saying what the song was talking about. Like when we were doing “Boogie Man” he said, “Put yourself in the place of being a nasty little shit…”

ANGUS Which wasn’t much of a stretch for Brian!

BRIAN We did all the vocals right in the control room, just sitting around like we’re sitting here now. Malcolm was sitting on one side of me with [engineer] Mike Frasier on the other. ’Cause I don’t like going into the vocal booth to sing. I like it to be more like when I’m onstage with the others. To have them around me like that.

GW Is that the way you cut the tracks too—all together, live in the room?

ANGUS Yes. Making a record, you’re trying to capture as much atmosphere as possible. And if you’re huddled in a room together, it mightn’t make for the best friendships, but it sure helps for a vibe on a record.

GW Did having your old drummer Phil Rudd back in the group contribute to Ballbreaker’s raw sound?

ANGUS Yeah. Phil’s more the rock and roll style. As a band, that’s what we really prefer.

MALCOLM Phil is an original member of AC/DC, from when the band first kicked off. That’s the feel we wanted to get back to. We figured we’re getting on a bit in years in this band. We just wanted to get tougher again. Ram it down their throats.

ANGUS We just met up with Phil when we were touring last in New Zealand. He said, “When am I gonna get a shot at having a play with you guys again?” Since leaving the band, I think he’d just been working in a small studio he put together.

GW What happened to Chris Slade, your last drummer?

MALCOLM Chris did a grand job with the band. There wasn’t any musicianship problems with him. Or a personality problem or anything. I mean the man is a great drummer—probably a far better musician than any of us guys. But it just got down to a particular groove that we needed. We just wanted to get things back to where they were in the early days of the band.

GW What went down in New York during the initial sessions for Ballbreaker?

MALCOLM We spent a lot of time trying to cut tracks in New York, but unfortunately we just weren’t happy with the sound we were getting. We were really looking for this thing to sound good. We were very particular. We laid down a lot of tracks in New York, but when we moved to Ocean Way [studios] in L.A., the first few days just sounded twice as good as anything we’d done in New York. So we decided to go right through and record all the tracks again. Not an easy task! But we felt that it was worth it. We’ve never done anything like that in the past. We’ve never been extravagant with recording. But we just felt these were good, tough songs and they should get their due. We went on a mission to find the right sound.

GW What did Rick Rubin bring to the party?

ANGUS Well, a big beard…

GW When did Rick first enter the picture?

MALCOLM Rick sat through the New York sessions with us. That’s when he entered the picture. But we’d worked before with Rick on a single [ “Big Gun” ] we did a few years back, for Arnold Schwarzenegger’s big flop movie [The Last Action Hero]. And Rick was basically just talking the same language as us, saying how he wanted to get back to more of the rock and roll feel we had in the earlier days. We felt, This could be good. Rick had been trying to produce the band for years. He’d written 20 times to our management, saying if there was ever a chance for him to produce us that he would love to do it. So we took him up on it.

GW It was reported that Rubin left the project before it was completed. That there was some kind of falling out between him and the band. What really went on?

MALCOLM I don’t think there was any falling out at all. Rick was there till the end. We all finished the album—we all put our pieces together in there. But, as I say, we were really on a mission to get the right sound. And you’ve got to wait for your moment in the studio—for the energy to be right. Especially when you’re in the same place every day. It can be like going to work. So there were a lot of low points. A lot of waiting around, I guess, and fiddling around with the sounds. So Rick wasn’t in the studio as often as you’d see a regular producer. But when he came, he did his thing.

GW Did he play an active role in getting the sounds?

MALCOLM Yeah, he knew what he wanted. He put his pitch in. He likes his snare sounds a certain way. Also, Rick helped keep things on the right track. Because sometimes you tend to settle for second best when you’ve been working on something for a very long time. Rick wouldn’t let us get away with that. You gotta hand it to the guy and give credit where credit is due.

GW What kind of guitar sound did you have in mind for Ballbreaker?

ANGUS We used a lot of older Marshalls. We’ve got a lot of them, we’ve had them for years. We actually spent a bit of time going through them all. We’d done a bit of that back in England, before we went to New York. We went through storage and pulled out the ones that we knew cooked and those we used on other records. Plus a whole bunch more that we bought in other places.

MALCOLM We tried to go back and find the old vintage tubes—all that sort of thing. Even down to the guitar strings that I use. I used to use Gibson Sonomatics 20 years ago. You can’t buy them any more, but our guitar technician, Alan Rogan, tracked down things like that for us. It all helps for that old analog sound, you know.

GW You’re noted for using fairly heavy strings.

MALCOLM Yeah. That came about by accident, really. Just to keep the band in tune! With two guitars—thumpin’ the Christ out of them at the same time—nothing ever sounded like it was in tune. But the thick strings came with a sound of their own. And once they’re on there, you get used to them. I can’t play without thick strings now. If I pick up Angus’ guitar, I’m throttling the thing. My guitar is like another instrument. I think of it more like piano playing sometimes. Because you can’t really bend the strings. Not that I’m supposed to, but you know what I mean. It’s not like a regular guitar player’s guitar, nor is it set up like one. It’s just set up for beating, really.

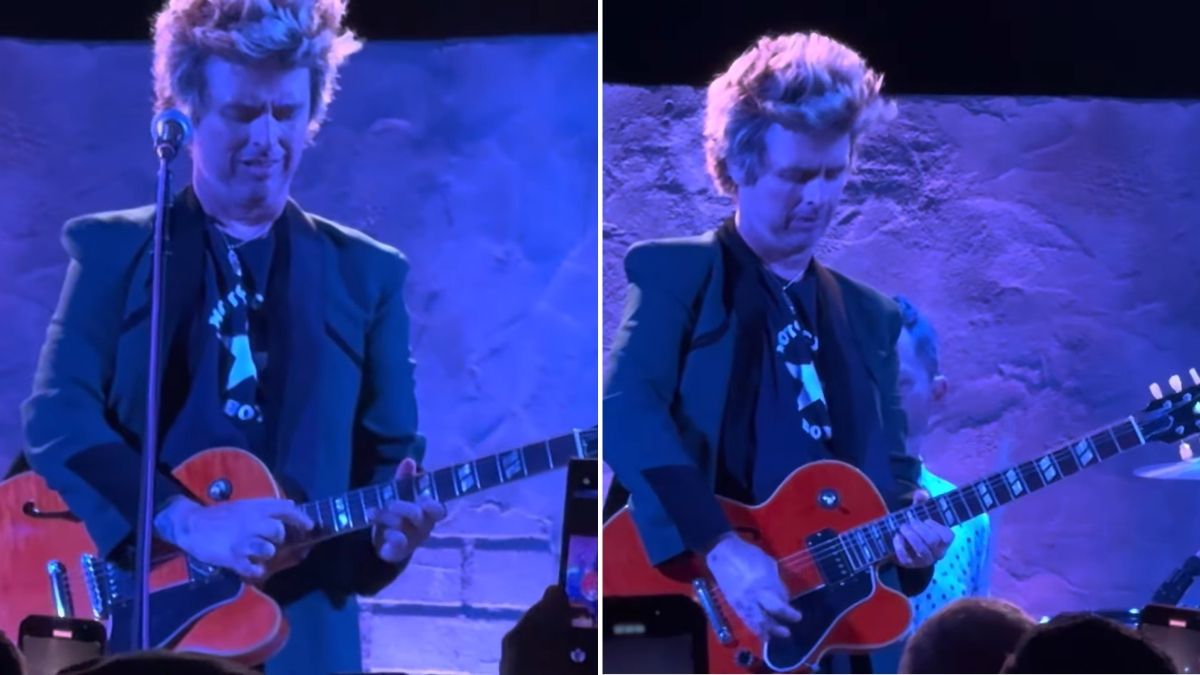

GW Did you use your Gretsch Jet Firebird for everything?

MALCOLM I did. It’s got its own sound, the original Firebird. I haven’t got another that could replace it, to be honest.

GW How and when did you first discover that guitar?

MALCOLM It was given to me. My brother, George Young, was in a band called the Easybeats [best known for their 1966 hit, “Friday on My Mind” ]. Him and his partner George [Vanda] produced the first five albums AC/DC did. And George gave me that Gretsch when I was 14, as a gift. It was his guitar—he’d used it and moved on to Gibsons. He knew I was keen on it and threw it my way.

GW Was that guitar used on any Easybeats recordings?

MALCOLM No, he couldn’t work with it. He’s more a solo player. He couldn’t get much out of it. He knew I had time to play around with it. He said, “Rip it apart. Do what you like. It’s got a nice feel, but it doesn’t sound the best. Maybe you can put a humbucking on it or something.” So I experimented with it. But the Gretsch pickups always sounded unique to me, so I stuck with them. [According to Alan Rogan, Malcolm installed a humbucker between the Firebird’s two Gretsch Filter’Tron pickups long ago. He didn’t care for the humbucker, but liked how the guitar sounded with the empty hole that was left once he’d removed the pickup. So he also removed the guitar’s original neck pickup, leaving just one Filter’Tron in the neck position. This is the configuration he employs today.] The Firebirds were only a cheap issue from Gretsch; they weren’t a wellmade guitar or anything. There was no quality control on those.

GW When you were first starting out, how did you work it out that you would play rhythm and Angus would play lead?

MALCOLM Well, Angus just always played lead. He never bothered with chords—he just wanted to solo. And I used to sit there and figure out tunes—the chords and all. I was playing guitar ever since I was about four, strumming along to Elvis or whatever. And, of course, when the Beatles came out, I was around 10 or 12. So I was trying to learn their tunes, with the chords. Angus played at an early age as well, but by the time he got to 10 or 11, it was Hendrix and things like that. So he was already hearing the guitar in a different way. There’s no doubt that when Angus is playing lead, he’s got the sound. He had it all there. But he’d say, “Mal, you should play some leads as well.” But I just felt so uncomfortable with it, you know? So I said, “The band’s rockin’. Let’s just keep things as they are.” All we wanted was to make a noise, to be honest. And it was always when the guys just let go and started ripping it up that the excitement was created. So we just stuck to that…that’s where the band’s essence came out of.

GW You guys lock together so beautifully. It’s uncanny.

MALCOLM Well, if you’ve been jamming together since you were kids, I guess it becomes second nature. We know each other so well, as most brothers do. And that comes out in the guitar playing. People says it’s unique, but we don’t see that.

GW How does it work when you write together?

ANGUS We feed off each other. We just jam away on riff ideas until something sparks. It might not happen on the first day. But maybe a few years later, two parts will just sound natural together. That’s the important thing, playing through the ideas until you find that natural thing. Rather than sticking things together, whether they belong together or not, and saying, “We’ll make ’em fit.”

GW Where does the pop element in AC/DC come from? Things like “Money Talks” or “You Shook Me”? Less heavy riffing, more the big major key hooks?

MALCOLM Well, a lot of that usually comes from the producers. [laughter] You come in with some nice riffs and, all of a sudden, the chorus is sounding poppy, you know? You hear it without backing vocals, but the producer wants to fatten it up: “Come on guys, this’ll be great.” There’s always a little bit of that. We gotta give some credit to Rick Rubin. He never did that with us. The more straight-ahead rock thing is what we always wanted to be. We never wanted to be a singles band. Unfortunately, you have to have a single to kick the album off and keep the record company happy. The marketing thing. But if you talk to us five guys, all we’re interested in is a good album. We try not to be pop at all—we pull right away from that. But there are some great riffs that just sing themselves. You don’t need anything on top. [Former AC/DC producer] Mutt Lange once said to us, “You guys would make a great instrumental band. It’s a shame sometimes to put vocals on these backing tracks.”

GW I really love the main guitar riff in “Hard As a Rock.” It’s so simple yet so effective.

MALCOLM That’s right. That riff can be bigger than any chorus. You’re right. It’s the simplicity sometimes.

GW Did you come up with that riff, Angus?

ANGUS Yeah. We were just jamming away and that came out.

GW But there, too, it’s the chords behind the riff that make it so effective. The way they anticipate the downbeat.

MALCOLM Yeah, you can build around a riff to see what makes for a little anticipation. We play with dynamics a lot in this band. Just being a straight-ahead four-piece band, you’re very limited. So we’ve got to use a lot of dynamics. We’re willing to play loud, soft… anything to achieve a thump at the end of it.

GW It seems like Angus gravitated toward simpler riffs throughout the new album. There’s nothing like “Thunderstruck,” with hammer-ons all over the place.

ANGUS I think you just have to do each thing as it comes to you. Once you’ve done “Thunderstruck,” you sit down and think, Well, what do we want to do for the next record? It helps if you have an idea of where you want to set the pace. The emphasis this time was just on getting a bunch of songs that we could play onstage and have it feel like it did when we were in a club 10 years ago, battling it out. The guitar riffs are just meant to suit that.

GW Were you thinking “blues” in your lead work for this one?

ANGUS I always think “blues.” There’s always blues elements in rock. And I’m a big fan of that sort of thing.

GW For the last two albums, Malcolm and Angus have written all the lyrics.

MALCOLM We would always write a lot of the lyrics anyway—just to get the phrasing for the vocals. We look on vocals as part of the feel. The words have to sit right with the feel, push it, sort of compliment everything. So we always used to write loose, rough words down anyway. In the end, we said, “We can finish these off. Let’s just do it.” Brian lives on the other side of the world, so we decided it was just easier to do it ourselves. This way when we brought a song to the guys, it was all ready for the band to play. So it’s just completing our operation, really.

BRIAN I prefer it this way myself. I never liked the pressure of having to come up with words. I actually enjoy doing the vocals more now. I can just go in and sing them and not worry about anything else.

GW Have you come under attack from any feminist groups lately for lyrics like “Cover You in Oil” or “The Honey Roll”?

ANGUS I don’t think we’ve ever really worried about that. You’ve got to remember that from Day One, especially when doing the kind of music we do, you’re always open to some kind of attack. If you’re not attacked for your lyrics, you’re attacked for your volume, or the size of your audiences. The last time we were attacked, I think it was someone in Europe crying foul over the cannons or something. [AC/DC fire off real cannons in live performances of “For Those About to Rock.” ] Or explosions. Or—and I really couldn’t work this one out—somewhere they were worried about air pollution. [Spreads his palms in bewilderment] I really didn’t see the connection between air pollution and us. I think that was just their way to give us a problem, you know? Those people have always been around.

GW Would you worry if AC/DC suddenly didn’t offend anyone anymore?

ANGUS As I say, we just take all that in stride. We don’t sit down and say, “Let’s offend.” That kind of thing never dawns on anyone when they pick up a guitar. That’s like saying you really are an instrument of evil, you know? In fact, my mother bought me the first guitar I ever had. She went out and got me a cheap, acoustic, 10-dollar thing and said: “Here’s one for you and Mal. Now behave yourselves.” I think ’cause they were older and we were a big family, they’d seen a lot and they weren’t worried about us playing rock. Whereas I know some of my friends’ parents wouldn’t let them go to a rock show or things like that. My parents never bothered about that. As long as you were home by the time they said you should be home. We never had those sort of rules.

GW I guess they’d been through it with your older brother, George.

ANGUS Yeah, they’d been through it with him. But he wasn’t the only one to play.

GW How many brothers are there?

ANGUS All together, there was seven boys in the family. And one sister. And all of us did get ’round to an instrument, although at different levels of technique. Some of us were well into it, and for others it was just a hobby. We’ve always had some sort of musical instrument around the house, whether it be a piano, a guitar, banjo, clarinet or saxophone. There was always something you could make a racket on.

GW Your brother Stewart became AC/DC’s manager. And it was your sister, you told me last time we spoke, who suggested you wear the schoolboy suit.

ANGUS That’s right.

GW Because of the schoolboy suit, you, and not the singer, are the most instantly recognized member of AC/DC. How has that affected the band’s dynamic?

ANGUS As a band, it’s made us a bit different. It made us stand out. When people ask me to describe AC/DC, I often say it’s four musicians and a gimmick. You don’t think much about things like that when you’re first starting out. But then, after a while, you’re playing in front of people and they want to see that. It’s like Yosemite Sam says in the Bugs Bunny cartoon: “I paid to see the high diving act, and I’m gonna see the high diving act!”

GW Do you ever regret the schoolboy suit? Do you ever wish you could just come out as yourself and say, “Here I am: a grown man, not a cartoon character?”

ANGUS Never. The great thing about the school suit is you can take it off and leave all that behind when you leave the stage. Like if you mess up, you can think, “Oh, it wasn’t me, it was that guy in the suit.”

GW So it’s a way of keeping your public life and your private life separate.

ANGUS Definitely, which I think is a good thing. So many performers get caught up in trying to live the legend 24 hours a day. That can really mess you up.

BRIAN People always come up to me and say, “Oh that Angus, he must be a wild one. He must take a ton of drugs and booze it up and fuck a million girls.” And I just go like this…[He shrugs, a non-committal smile spreading over his swarthy, haggard features.] I don’t know if I should burst their bubble—if I should tell them, “No, he’s actually a very quiet, nice guy. A teetotaler. All he does is smoke fag after fag.”

ANGUS I don’t really want the focus to be on me when we’re onstage. I’m only part of AC/DC. If they didn’t do what they do, I couldn’t do what I do. That’s how I’ve always looked at it. I suppose sometimes I wish I could just stand in the back and play. Then you really are “in the band.”

GW I don’t think any of us would want you to stand in the back.

ANGUS No. And I really enjoy what I do. But sometimes I look at Malcolm playing— just that solid rhythm thing he does—and I’m awestruck. But you see that with all bands. The Stones are lucky in that they’ve got their Charlie Watts and Keith Richards. You take those away and all you’ve got left is Mick jumping around onstage. That’s okay. But the other two, they’re the real rock force. They’re the ones that do the pushing. Then you can sit back and enjoy the whole thing. You’ve got two guys to keep your ears amused as well as something to catch your eye.

GW Mick’s solo efforts certainly have not had the same character as the Stones.

ANGUS Yeah, but Keith’s have.

GW AC/DC are sometimes compared to the Stones. You’re both archetypal rock bands that seem to soldier on no matter which way the fashions blow.

ANGUS The Stones have been there from the beginning. You have to respect all the things they’ve done. I think they carved the road for us. I sometimes think AC/DC are more like the Three Stooges.

GW But there are five of you.

ANGUS Well, you get two more.

GW What’s your take on alternative rock?

ANGUS I like anything that’s rock. But I’m always skeptical of the media thing. There’s always some new flavor that people are talking about, and I’m wary of that. At the time we started, people didn’t take as much notice of what the media said. We didn’t have this global fucking communications network that we have now. You’d hear something and say, “I like that.” Then you’d go see the group live, and if you were still pleased by what you heard and saw then, okay, you’d found a new group that you thought was cool. But these days, the look is so much more important. And I’m always wary of that. ’Cause something can look nice, but it mightn’t be so nice. [laughs]

GW AC/DC has lasted when a lot of others have come and gone. For example, now people are saying that the Eighties hard rock bands are dead.

ANGUS I think sometimes people tend to count things out too soon. Sometimes those same things come back and smack them in the face. You see that when you’ve been around for a while.

GW How have you seen AC/DC’s audience change over the past five years?

ANGUS You see different generations now. Older people and younger people come to the shows. For me it’s funny, ’cause you meet some of the younger ones and they’re talking to you and you think, Hey, I’m not your father! I’ve got about the same brain as a teenager.

GW This could be said of AC/DC: you’ve maintained your youth.

ANGUS Well, we just like to kick it out. If you know what you do well and stick with it, I think you can appeal to different generations— strike a chord with them.

GW So, there are no plans to retire?

MALCOLM No mate, no mate. No plans yet.

GW A final request. My wife would really like to hear AC/DC do a cover of “Take a Little Piece of My Heart.”

ANGUS By Janis Joplin. Good song, that.

BRIAN A little while ago I got invited down to hear Melissa Etheridge. And she did a cover of “You Shook Me.”

GW How was it?

BRIAN Fookin’ great! That was the first time I ever heard a band play that song right.

ANGUS [looking hurt] What about us?

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

“The rest of the world didn't know that the world's greatest guitarist was playing a weekend gig at this place in Chelmsford”: The Aristocrats' Bryan Beller recalls the moment he met Guthrie Govan and formed a new kind of supergroup

“We hadn’t really rehearsed. As we were walking to the stage, he said, ‘Hang on, boys!’ And he went in the corner and vomited”: Assembled on 24 hours' notice, this John Lennon-led, motley crew supergroup marked the beginning of the end of the Beatles