AC/DC: Young At Heart

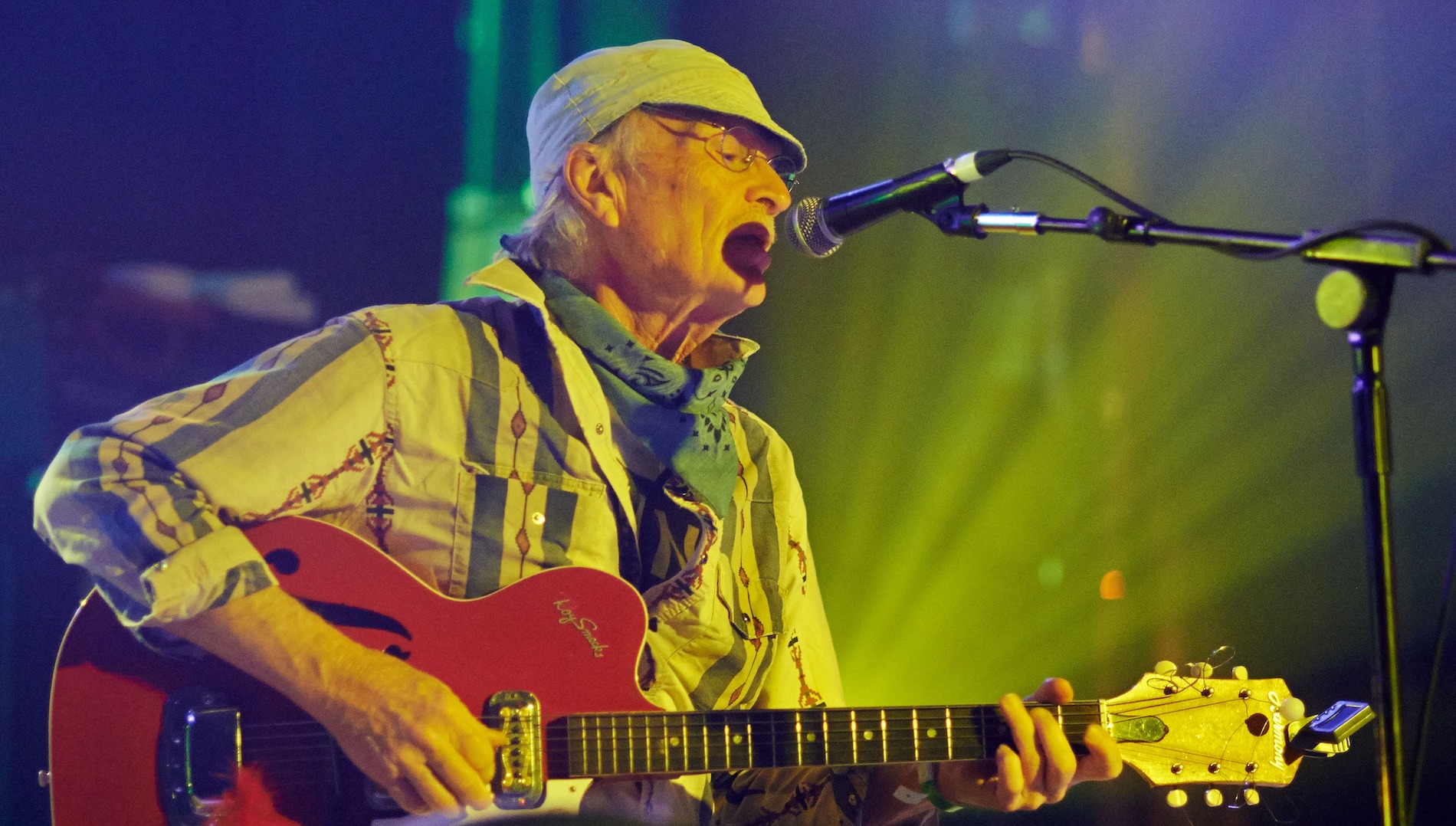

In Guitar World’s first-ever interview with Angus Young, the guitarist revealed the dirty secrets behind his legendary sound.

In an industry gone mad with detail, where every guitarist knows to the nth degree not only the gauges of his strings but the alloys which made them up, where every player has a rack of pedals, gadgets and gizmos which would befuddle most any NASA representative, Angus Young stands apart as a guitar player who’s uninterested and unamused. When referring to his variously dated Gibson SGs, Young calls them “This guitar” or “This thing.” Rarely “This SG.” He admits to not knowing the names of chords; and only upon joining AC/DC did he develop any sense whatsoever of chord names and descriptions. But for all his lack of technical knowledge, Angus Young is one of the rare players who has been able to propel the normally monolithic properties of hard rock out the window and replace them with intriguing overlays of rhythmic instruments.

Young, a feverish and manic performer, embodies a raucous guitar style which has made him and AC/DC the dirty darlings of Australia and catapulted the quintet into international status. Angus combines rapid lead phrases with chunk rhythms (the main tempo is created by brother Malcolm on rhythm guitar) and an outlandish yet forceful stage persona has elevated Angus’ name to the upper echelons of rock players.

Offstage, however, he is somewhat more subdued, sipping hot tea, forever joking, and continually moving various parts of his anatomy including head, hands and feet (not to mention the constant rolling of eyes).

What is not constant, though, is the approach and direction of AC/DC’s music. Granted, the Australian quintet could hardly be labeled middle-of-the-road or pop rock (they would be more than likely to extract the labeler’s teeth with a pair of needle-nose pliers if such an event occurred) but to brand them strictly as mutant heavy metal is a false appraisal. Young, who began playing at age five on a banjo restrung with six strings, has an actual disdain for most power rock ensembles. The interplay between Angus and elder brother Malcolm (whom the younger Young cites as a far more accomplished player than himself) is the prime reason for taking AC/DC more seriously than the deluge of other monster rock bands. The thinking man’s heavy metal group? Hardly. But certainly they inject more in their music than might be heard in one listening.

“We try to do everything with a fresh approach,” offers Young. “We try and get an idea of what we basically want from the album. We don’t like to leave people dry or have them say, ‘These guys have left us and gone off to something else.’ That self-indulgent thing. So we try and keep it basic. A lot of people say we work a formula, but we don’t. We try a fresh approach all the time. “I saw Deep Purple live once and I paid money for it and I thought, Geez, this is ridiculous. You just see through all that sort of stuff. I never liked those Deep Purples or those sort of things. I always hated it. I always thought it was a poor man’s Led Zeppelin.”

Tracks like “Back in Black” and “You Shook Me All Night Long” (both from Back in Black) and virtually all of Flick of the Switch (their newest) are strong examples of this weaving of guitar parts and textures. Angus, who received his first real electric guitar (a Hofner) when sibling Malcolm acquired a Gretsch, is at odds in explaining how these guitar parts are created.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“He’ll get something and I’ll play along,” claims the guitarist whose only lessons were in the form of watching his brother play. “It’s a natural thing. I suppose it’s just something we do well together. He seems to have a great command of rhythm and he likes doing that. That, to me, is more important because if we’re playing live and something goes wrong with my gear and my guitar drops out, you can still hear him and it’s not empty. He’s probably got the best right hand in the world. I’ve never heard anyone do it like that. Even Keith Richards or any of those people. As soon as the other guitar drops out, it’s empty. But with Malcolm it’s so full. Besides, Malcolm always said that playing lead interfered with his drinkin’ and so he said I should do it.”

A self-proclaimed “illiterate” on the instrument, Young never really took the guitar seriously until age 14, nearly 10 years after he transformed that banjo into a makeshift guitar. At the time he received the Hofner he began a more serious evaluation of his stance and even managed to obtain a $60 amplifier which would turn the tubes blue when a push/pull treble pot was activated.

“I remember one of the first gigs I played with that amp was at a local church. They wanted someone to fill in with the guitar and my friend says, ‘Ah, he can play.’ And so I dragged the amplifier down and started playing and everyone started yelling ‘turn it down!’ ”

Not to be undone, he continued playing and listening (mainly to old rock and roll records like Chuck Berry) and in a twisted sort of fashion became adept at lead work prior to a command of rhythm. While he does nurture a pure distaste for the solo artist (he is a company man) and for that matter soloing itself, it was a technique acquired with little problem.

“Soloing was pretty easy for me because it was probably the first thing I’ve ever done,” says Young. “I just used to make up leads. I never even knew any names of chords until Malcolm told me and then I picked it up from there.”

Encouraged by improvements, Young outgrew the Hofner and bought a second-hand Gibson SG. Approximately a 1967 model, the instrument was played until just a few years ago when wood rot (due to excessive moisture from sweat) and neck warp forced him to look for a replacement.

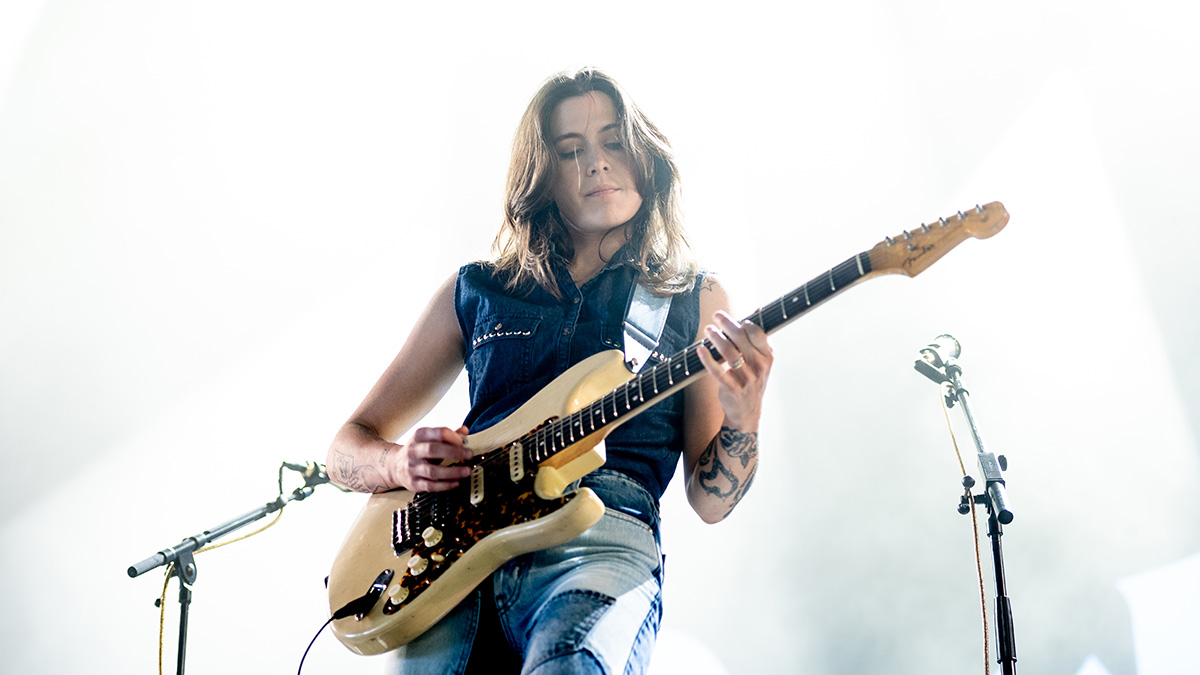

“It had a really thin neck, almost like a custom neck,” describes Young, whose pixie-sized hands would find such a neck to his liking. “I liked the SGs because they were light. I tried Fenders but they were too heavy and they just didn’t have the balls. And I didn’t want to put DiMarzios on them because then everyone sounds the same. It’s like you’re listening to the guy down the street. And I liked the hard sound of the Gibson.”

That particular instrument has been difficult for Young to replace. It had a remarkably thin neck (Gibson made 1 1/2” and 1 1/4” necks and this was one of the latter) and after searching virtually every major guitar shop in the world has yet to find an equally playable instrument.

He used this guitar from 1970 (when he bought it) until 1978 (he did replace the original pickups after one year of use with another set of Gibson Humbuckers) when it was set aside for another SG he purchased at a pawn shop in New York. A Gibson reject due to flaws in the finish, it is similarly a circa 1967 model with that same thin neck featured on his original piece. It is the shape of the instrument as well which has attracted Young, the two horns allowing for easy access to the higher frets.

“And you can do a lot of tricks on it, too,” he chides.

Just as he has been faithful to the Gibson SG, so has Young been a stalwart of the Marshall amplifier. Toying with other amps (Ampeg in particular) led him to the conclusion that the Marshall 100-watt stack is “the best rock amp” and while his stage setup does vary, it is basically an arrangement of four stacks hooked in series via splitter boxes. The tone controls represent little more than gibberish to him—performing with the English units for over a decade has directed him to rely upon certain settings. All four stacks are set virtually the same and read: volume at full; treble and bass at half; midrange at half; and presence at zero. If there is a lack of top end depending on the configuration of a hall, he will kick on the presence as compensation.

“Just over the years and fooling around with them you find something that sounds right. I’ve found with Marshalls if you’re using a fair bit of volume, you should put the bass and treble at half because they’re working at that point.”

Angus makes special visits to the Marshall factory outside of London to play through a series of amps before selecting the proper one(s). He says the units are then doctored to resemble the old-style amps which were very clean and had no master or preamp settings.

Young’s live sound is a blistering combination of awesome volume tempered with the cut of treble and made full by the wash of bass. The quartet of stacks is engaged more for the spread of sound than for the sheer loudness. Angus runs about the stage like some schoolboy on meth (his costume is the Little Lord Fauntleroy white frilled shirt and matching jacket and shorts) and he must be able to hear his guitar at any position on the stage.

Except for the arena shows where it is mandatory for the P.A. to disperse the sound, AC/DC will dispense the music strictly through stage volume, thus assuring that what they hear is exactly what the audience is listening to.

“That way, it’s your sound coming out,” explains Young. “A lot of times you’ll hear bands and it’s a different sound coming out than what’s onstage. Because you can clean it up [through a P.A.] and make it sound completely different than what they really sound like. We’ve always been wary of that and that’s why we always tended to have a lot of amps onstage. And also it has a lot better feel to it especially when you’re playing hard rock music.”

Angus’ style is indeed a hard rock approach. He “bashes” his Gibson strings (gauges .009, .011, .016, .024, .032 and .042) with a Fender heavy pick, his crunching right hand technique originating from his early use of the barbed wire–like Black Diamond strings. Like train tracks, they required Young to develop a heavy right hand to derive any sound whatsoever from them. He does employ up/down strokes as well as the middle, ring and small fingers of his right hand to create a more stringy effect. On a given night, he has been known to use his teeth as substitute dental digits, though seven of them are now false from when he failed to execute a Superman leap one evening onstage.

It is a true test for Young to recall the types of picks and strings he uses. While he does know more than he owns up to, his description of himself as a guitar “illiterate” is not far wrong. He learned to solo mainly from watching his elder brother Malcolm play and the idea of scales and figures is as foreign to him as American beer. Most of his solos are approached by “feel” and even his recorded work is for the most part live solos with little overdubbing.

“I don’t regard myself as a soloist. It’s a color, I put it in for excitement. It’s no great loss if a solo has to go. We’ve made songs without solos.”

Uncertain about scales and note names, he has never had difficulty in resisting the lure of the pedal. His sound is uncluttered and pure and one of the true milestones of rock guitar (Def Leppard owes more than a passing glance to Young’s sound). Early on in his career he did fumble with a fuzz-wah but found that his foot “kept going right through it.” The only accoutrement engaged is a Schaffer wireless system he obtained in 1977 and has been using ever since.

“I found that pedals were too much to fool around with. You’d be halfway through a solo and the batteries would go dead and conk out. And if you tread on the lead going to the pedal, something would always go wrong. Or some crazy kid would pull the lead out just at the moment when you’re about to do your big number on it.”

Similarly, Young hooks up no pedals in the studio through he does trade in the four Marshall stacks for an old style 50-watt model. His guitar is basically flat, an approach used from the beginning, and even on the newest album (Flick of the Switch) he went for a very natural sound.

His sound on Flick of the Switch embodies that cleanliness and yet there is an edge and atavistic grace rumbling from below. As on past records, the bulk of his solos are recorded with the track, owing to his lack of interest in working out overdubbed parts (he is more than capable of it but has an aversion to it) and his inability to see himself as a solo-playing musician.

“We wanted this one as raw as possible. We wanted a natural but big sound for the guitars. We didn’t want echoes and reverb going everywhere and noise eliminators and noise extractors. Getting the sound has always been the easiest part of the guitar. Also, if you’re playing it right, it’s going to sound right somehow. I mean, you gladly turn down if it’s going to sound bad. It’s not like, ‘I have to have a wall of amps and a candelabra on top.’ If you hit a chord and it’s distorted, you clean it up. It’s all what you hear. You fiddle around until you get a good sound. For me, I prefer the sound to be clean if I can get it clean. If you can get that natural distortion, fine, because I don’t believe in pushing the hell out of the amps, because they become muddy and whooshy.

“I tend to look at the music as a song; it sounds a bit funny talking about it as someplace to play a solo. My brother would beat me up. People tend to see me as a soloist. Poor people. You’d think they’d have something better to do. I mean there’s a lot of comedy on TV worth watching. Yeah, people see that but I don’t. I look at it as a band. I think Pete Townshend is rotten without Roger Daltrey and the Who. He’s quite boring actually. Or the same with Zeppelin without John Bonham. To me it’s not the same. I mean, there are solo people who just do that sort of thing. I like it as a band, as a unit. You should hear me on my own. It’s horrendous.”

“The main acoustic is a $100 Fender – the strings were super-old and dusty. We hate new strings!” Meet Great Grandpa, the unpredictable indie rockers making epic anthems with cheap acoustics – and recording guitars like a Queens of the Stone Age drummer

“You can almost hear the music in your head when looking at these photos”: How legendary photographer Jim Marshall captured the essence of the Grateful Dead and documented the rise of the ultimate jam band