“Malcolm said, ‘I've got this riff, it's driving me nuts.’ It's three o'clock in the morning and I'm trying to sleep. I said, ‘It sounds fine to me.’ That was Back in Black”: Through 50 years of triumph and tragedy, they remain hard rock's greatest titans

AC/DC's Angus Young traces the lineage of one of rock's greatest bands – from his air-tight six-string chemistry with his brother Malcolm, that time he tried one of Malcolm's guitars, and why he avoided Strats at all costs

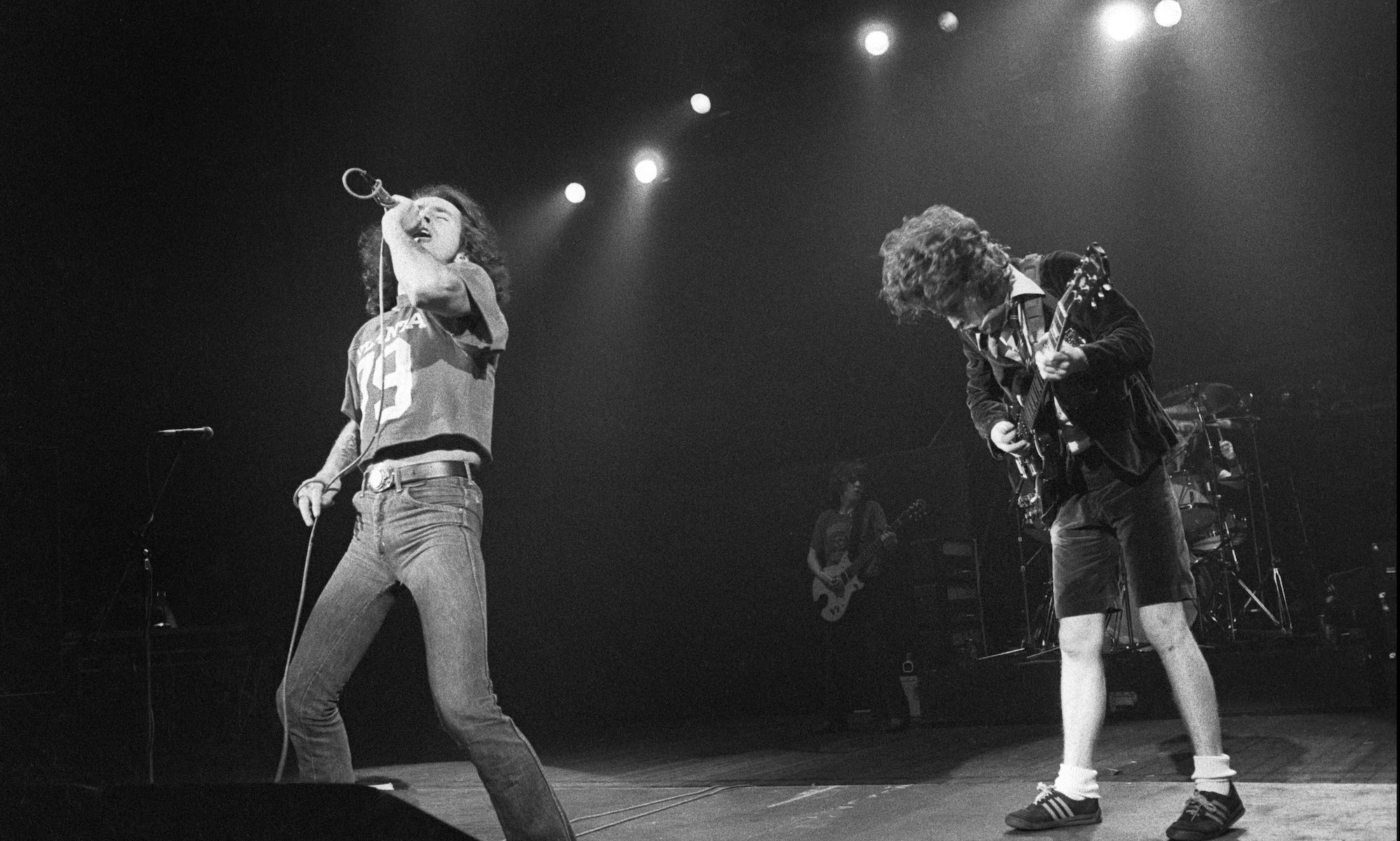

Great rock and roll needs no explanation; it hits you so squarely in the chest that you start feeling good long before your brain has had time to figure out what happened. AC/DC know this. For 16 years they've been making powerful, masterful rock and roll – without pretense, self-analysis, or the slightest regard for the never-ending parade of fashion.

Those 16 years are summed up beautifully on AC/DC's new live album, Live – a collection of classic after classic from the quintessential live hard-rock band. Through it all, Angus Young's lead guitar rages like a forest afire.

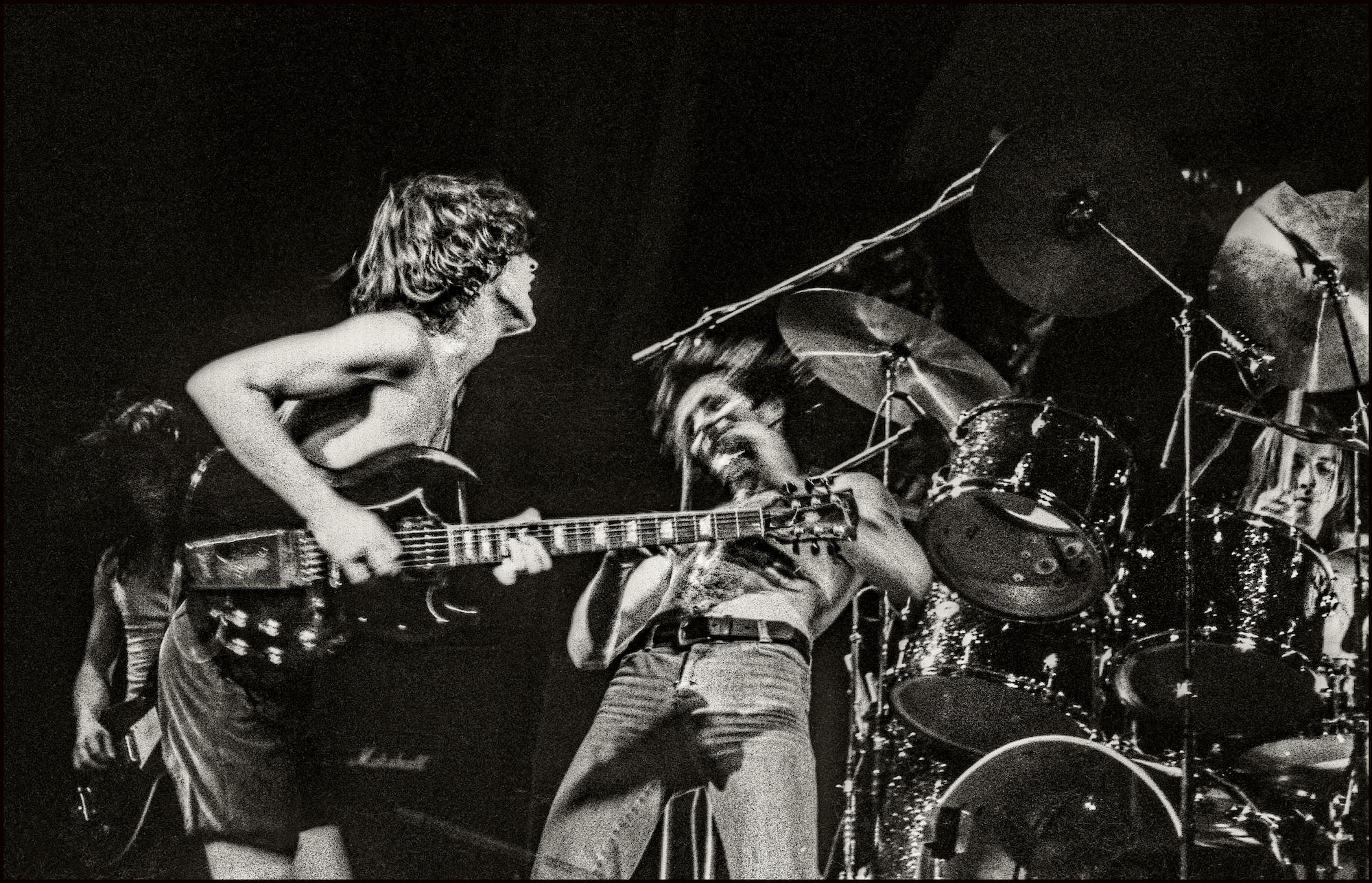

He stands no taller than five feet, but he throws every ounce of his compact frame into each power chord and stinging lead, playing with brutal conviction. As singer Brian Johnson says, “You cannot bullshit the kids.” AC/DC wouldn't know how to try.

In New York to promote Live, Johnson and Young come on like a duo from a Charles Dickens novel: a boisterous highwayman from the chilly north of England and a diminutive, wise-cracking Artful Dodger.

Though Angus has not lived there for years, his speech is still peppered with the sharp cadences of Australia, where he and his brother, Malcolm, started AC/DC all those years ago.

With each wry observation, Angus squints one eye behind a perpetual cloud of cigarette smoke that trails up and gets lost in his fine, auburn hair. He and Johnson throw themselves wholeheartedly into the business of talking barre chords, bared bottoms, and other rock essentials along the Highway to Hell.

Your performance style is so strenuous, Angus. Have you ever hurt yourself onstage?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Angus Young: “Sure. I've lost teeth. I mean I don't go out there to do myself a deliberate injury. But when you're on the road for that length of time, you're bound to twist an ankle or something. I once had splints on my fingers. I soon learned how to play slide with them on! I've jumped off amps and fallen ass over tit – made a complete fool of myself.”

What was your most embarrassing moment onstage?

Young: “Well, I've had my pants fall off. All of a sudden my wedding tackle was out there for all to see. You know, I've even had my shorts stolen a couple of times.”

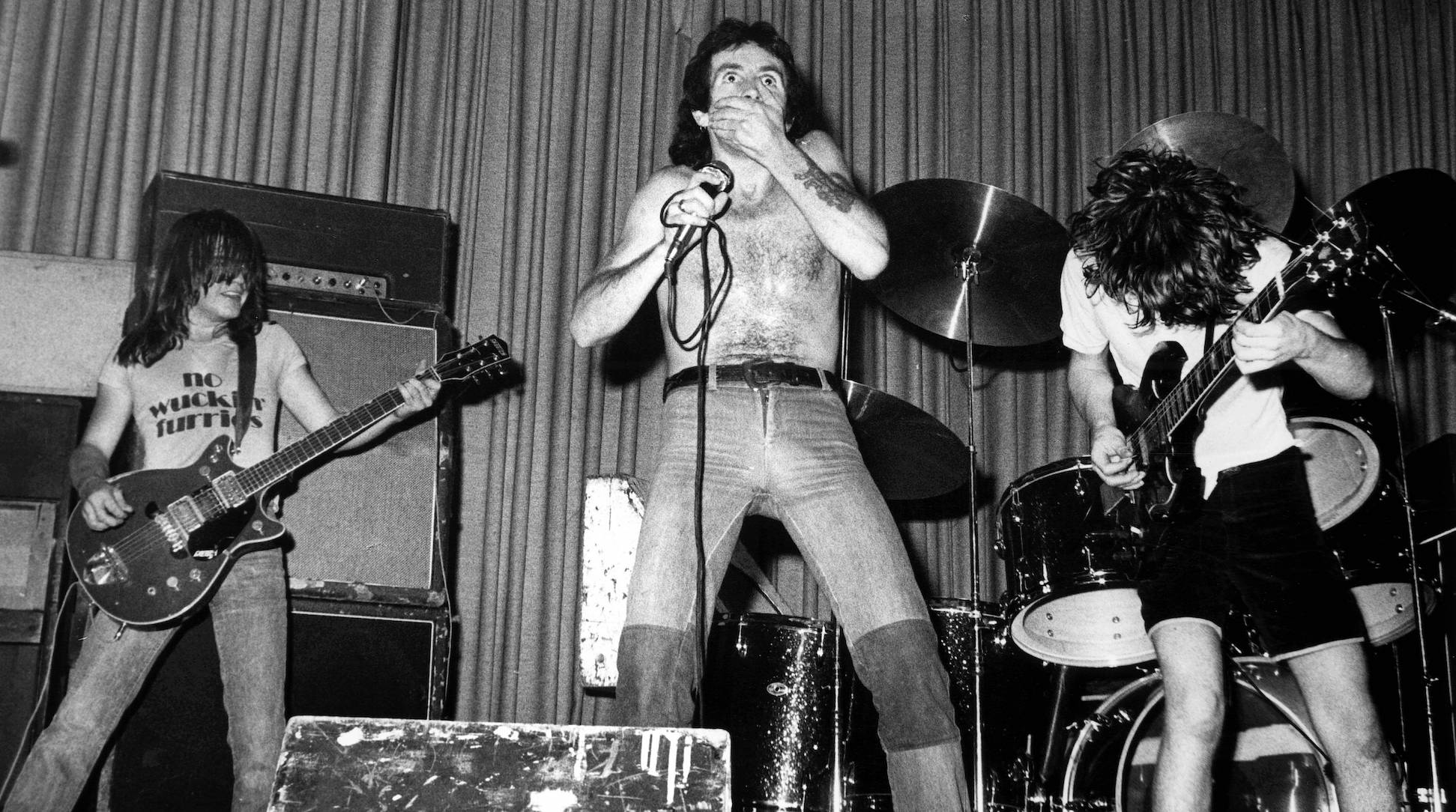

What's the origin of that time-honored part of your show where you strip off and moon the audience?

Young: “A lot of that came from the days when we'd be playing clubs and it'd be hot inside. So I'd take off my jacket, and half the audience would go ‘whooooooo.’ Especially with my physique – I'm not exactly Mr. Arnold Schwarzenegger. So it's all built off that. I'd take off my shirt and the drummer would go ta-dump. A bit of cheap cabaret, really.

“And the mooning thing... well, it's a great way to shut up a heckler. Or to get attention back up on the stage.

“One time we were playing this big festival in England and there was this woman photographer with a real Dolly Parton physique, you know? She gets up and walks across the front of the stage. And of course more than half the audience are hotblooded males; so they're all following her like this. [rolls his eyeballs to the right] And my brother says, ‘You better do something quick to get their attention back.’ So I mooned 'em. That certainly jolted them back quick. Very popular with the law, too.”

I'll bet!

Young: “Oh, yes. On one of the early tours of Britain we had the vice squad on tour with us the whole time. 'Cause Bon... [the late Bon Scott, AC/DC's first singer]... he took the French language, you know. Well, he had a colorful language anyway.

“I remember there was many a time in Australia, playing in these outback places, where we'd have to put up bail money. And if we did anything wrong – like me pulling my pants off or Bon swearing or anything – we'd lose the bail money.

“The mayor and the councilmen would come along to the show to monitor us. They thought it was a great thing. They invented it. Not us. It was their way of trying to stamp us out.

“I remember once Bon getting up there and saying, ‘I've been told we can't say ‘fuck.’ Okay, we won't say ‘fuck.’ I've been told we can't say ‘shit.’ Okay, we won't say ‘shit.’ They left out ‘suck.’ But we won't say that either...’ You know? Our bankbook didn't grow, but our popularity did.”

You've said somewhere that you can't play guitar well unless you're jumping around like a lunatic.

Young: “Yeah, well I go with the guitar, because I'm pretty small. On most people, a Gibson SG looks small – like a violin. On me, it looks like a big guitar. I've got small fingers, too.

“Now, when most people bend a string up, their finger bends the note. With me, my whole body's got to go. [He falls into Angus stage move number 1, miming how he uses his entire forearm to bend a string.] I hug the guitar, if you want to get technical about it. Now for vibrato... [he convulses with laughter as he illustrates]... I've got to shake me leg a little. When you're a little guy, there's not much pull on the strings – especially with the heavier gauges.

“The most important thing for me onstage is playing the guitar. The whole epileptic routine – whatever I do up there – comes out of that. I do become a little... possessed, as Malcolm says. But there's nothing Satanic in it. I do become another person. But that other person comes from me concentrating really hard on playing the guitar.”

Do you feel that AC/DC are essentially a live band?

Young: “I think that all good bands are essentially live bands. The great ones – the ones that last – are the ones that had that approach. Your Stones, Who, whatever. Your only real gauge for AC/DC is if we play someplace and people come to see us the next time we play there. That's the only way we know if we were good the last time. You can't trust the hype side of it.”

Do you see a lot of fans from the beginnings of your career – 1976?

Young: “Sure we do. There's a lot. You can tell. The older ones are in the back.”

We weren't a punk band, but they'd put us on the same bill as punk bands. And they sure got a shock when they started spitting at us and we spat back

Angus Young

Brian Johnson: “We're just about on first-name terms with some of them. Some guys have got a standard pass to get in. They know the crews and all.”

Young: “Europe accepted us before America did. So when we went through Europe last time it was like an army following us. Kids with tents coming out and stuff. You walk in and they give you the set list they want you to play.”

Johnson: “We feed 'em, too. There's always a lot of food backstage – more than we can eat. So as we're leaving the venue, we say, ‘Okay guys!’ And the kids come in with haversacks and fill them up – so they can get to the next gig.”

Young: “They've got great networks, the fans. They can tell you what happened the night before. Like if you played a few different songs or did a song a bit faster the previous night, they know all about it.”

Is it kind of like the Grateful Dead phenomenon?

Young: “Naaooowww. I mean, the last four letters of the Grateful Dead say it all, don't they?”

Brian, you joined AC/DC in 1980, after the band had enjoyed a bit of success. Did the band live up to your preconceptions of what they were like?

Johnson: “Well, I hadn't known about AC/DC long enough to have a preconception of them. I was up in Northern England. And it was just six months before I auditioned for them that I first heard them.

“A couple of me buddies... Malcolm Waley, I'll never forget... he brought back an album, 'cause he'd seen them at the Newcastle Mayfair. And he said [his voice drops even lower than usual], ‘You gotta fookin' hear these! Fook!’ [To Angus] You know Mal.

“At the audition, we started doin' Whole Lotta Rosie; I knew it 'cause there was a big buzz in England on that song.

“Europe and England were the first places where the boys were really gettin' red hot. It was great 'cause it was right in the middle of the big punk thing. Now, I heard punk and I said, ‘I fuckin' don't get it. I know everybody's raving about it...’ But I didn't like it at all. So with the boys, at least there was something out there that was decent. Ya could tap ya foot to it – know what I mean?”

Young: “At that time he's talking about – the middle Seventies – we were giving punk music a good name. Because that was the word they used to describe us – punk band. They'd get a wrong idea. We weren't a punk band, but they'd put us on the same bill as punk bands. And they sure got a shock when they started spitting at us and we spat back.

“We were never ones for getting slumped under a tag or filed under A, B, or C. We started as a rock and roll band. That's what we play – what we do best. We never claimed to be anything else. And then in the Eighties, they'd slump us in as a heavy metal band. Even before that they had other things: power pop. Crap.”

Johnson: “You put all the names together and it spells bullshit.”

Young: “It's true. I mean, okay, the word ‘blues’ conjures up something definite. You know where you're going. It says it right. But the heavy metal thing? I immediately think of men in armor. And then that split leg routine. You know what I mean?

It ~was~ a highway to hell. It really was. When you're sleeping with the singer's socks two inches from your nose, that's pretty close to hell

Angus Young

“There's more to playing the guitar than being able to do a leg split and wearin' a pair of tights. The heavy metal tag offended me more than the punk thing. 'Cause I thought, ‘Jesus, what have they conjured up now?’ Then just because you call an album Highway to Hell you get all kinds of grief. And all we'd done is describe what it's like to be on the road for four years, like we'd been.

“A lot of it was bus and car touring, with no real break. You crawl off the bus at four o'clock in the morning, and some journalist's doing a story and he says, ‘What would you call an AC/DC tour?’ Well, it was a highway to hell. It really was. When you're sleeping with the singer's socks two inches from your nose, that's pretty close to hell.”

Presumably it's gotten a little better now.

Young: “It has. He can do his laundry now.”

Johnson: “I've got two pair of socks now.”

So Angus, did you listen to a lot of blues early on?

Young: “Sure. That was my diet. Other kids would come to school with the latest Top 40 thing. I was always buying a lot of imports: Muddy Waters. That music.

“When I was young, one of the earliest records I heard was Little Richard's You Keep a Knockin'. I think I nearly invented rap with that record: I'd take the needle and keep putting it back to the same spot, to the blues bit, over and over again; 'cause that was the best part of the song. My mother said, ‘You touch that needle one more time and you're going to have a very sore fist.’ But I couldn't help it. I just loved that one bit.

“I was never a lover of the harmony-type stuff. For some reason that seemed too... eeuuuewww... it brought in that sweetness. When I heard the Beach Boys, I just thought it was an older version of the Chipmunks.”

Johnson: “Hah – at the real speed!”

Young: “You know what I mean. 'Cause it was like [sings in a hilariously nasal California accent], ‘We're suurrfun Yew Ess Ayyy.’ Then when my family immigrated to Australia [from Scotland, in the mid Sixties], you'd see these kids that had nothing to do with the real thing, but they all looked like they came out of Hawaii Five-O. Standing there with these great wooden lumps of board.

“I'd never seen a surfboard in my life. But they've all got these bits of wood, and they're all going, ‘Surrrfun Yew Ess Ayy.’ I went home to my mother and said, ‘Mum, I think they put us on another planet.’”

Johnson: “In Newcastle [England] we didn't know what water was.”

Young: “It was oil.”

Johnson: “The only water we had was what you put in your whiskey.”

Young: “That's right, Newcastle invented the word pollution.”

As soon as I saw the SG, I knew that was the one I wanted

Angus Young

So you weren't impressed by the ‘American-ness’ of it all?

Young: “Oh, no, no, no, don't get me wrong. I love what's come from America, musically. But I don't think the people here see it for what it is a lot of times.

“For me, the culture is blues music. That's what I grew up on, and I have great respect for Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Chuck Berry, Willie Dixon... If those people weren't there, you wouldn't have your Stones, your Zeppelins, the Who... all the big blues-based bands. The Beatles – same thing.

“I mean, if Paul McCartney played in Boston tomorrow, he would finish off the night with seven or eight Little Richard songs. That, to me, is rock music. The other things are really the housewife, ‘cry in the tea towel’ shit. That ain't rock music.”

When did you start up with that SG, Angus?

Young: “Just as I came out of school. I saved up my pesos and went to the guitar shop. I always wanted an SG.

“I had a friend, an American guy, who had a Gibson catalog. As soon as I saw the SG, I knew that was the one I wanted; I think it was because the horn things [i.e., the sharp cutaways] reminded me a bit of myself. And the other thing, when I saw the Beach Boys with a Stratocaster, I think that also swayed me the other way. It didn't look right. And that surfin' thing was popular at the time.”

That Fender sound.

Young: “I'm not condemning it. You've got your Hendrixes and all that. But even he said he didn't like playin' surf music.”

The Who did.

Young: “Well, yeah. They were a strange case.”

So you discovered the guitar of your life pretty early on.

Young: “Well, not right off the bat. I mean, I played other guitars. I had an acoustic guitar first. My mum got it for 10 bucks when I was nine or so. She got both me and Malcolm one, so there'd be no fighting over it. There was always a guitar around the house, always some brother that had some guitar lying about somewhere.”

Were you influenced by your brother George being in the Easybeats? [The Easybeats were a mid Sixties beat group that had a worldwide hit with Friday on My Mind.]

Young: “Not that much, 'cause he formed that band as soon as we arrived from Scotland – formed it from the immigrant camp. So from the moment we arrived, he was out playing a lot. I never really saw him much. And then I had another brother, a saxophone player, who had also taken off. He went to London and then ended up in Hamburg, Germany, during the Beatles' times.

“My father wanted to get us all off the music kick – he thought we should be working. That was his thing. That's why he moved to Australia. So at school, I wasn't allowed to tell anyone that my brother was a member of a band. I remember one headmaster found out and gave me a hard time over it.”

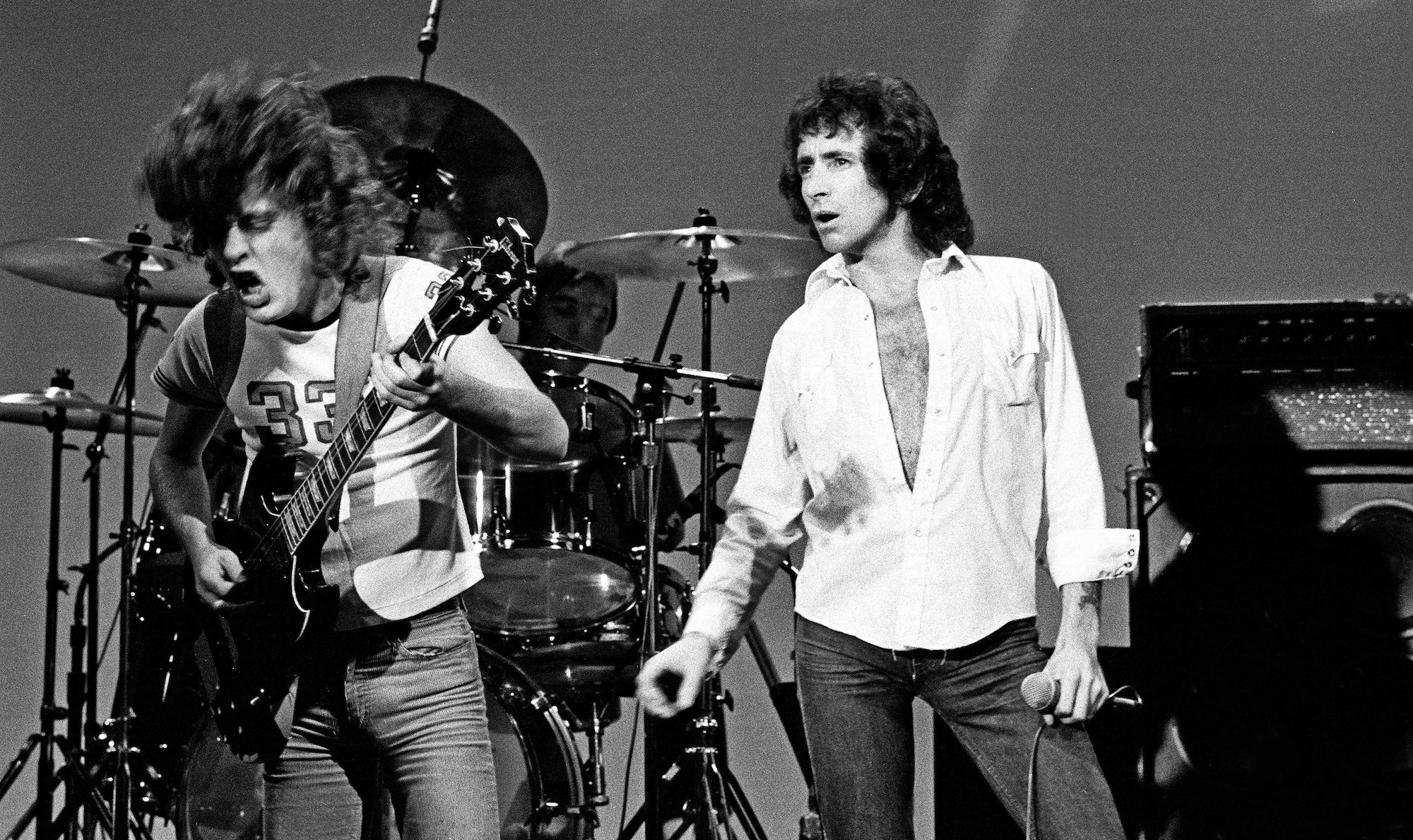

Did you and Malcolm start your thing together?

Young: “Not really. We just used to play away. George would say to Malcolm sometimes, ‘Here Mal, pick up the guitar.’ Like if he was working out an idea or something. 'Cause Mal was very competent. He's a great all-around guitarist. I know it says ‘rhythm guitar’ on the albums. But for me, if he sits and plays a solo, he can do it better than me.”

Does he ever play solos on records?

Young: “In fact, there's a couple of solos from him on our first album. But even then it's the way he plays rhythm – it's got that distinct sound, especially with that Gretsch. I've tried to emulate his rhythm style myself, at home, with one of his guitars, and it's no easy task. He's got those .32 guitar legends big thick strings on it, like tram tracks, you know? It's all in his little wrist.”

![AC/DC - It's A Long Way To The Top [Official Music Video], Full HD (Remaster, Resync and Upscale) - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/g-qkY2yj4_A/maxresdefault.jpg)

You guys have an amazingly tight thing together.

Young: “I think that's part of the brother thing, too. It used to be a game, sort of. It becomes instinct with you. And my other brother George was so quick that you learned a lot when you were with him. Especially when you were 14 or something.

“He'd pick up a bass and hand you the guitar. And you'd think you were incompetent, but before you knew it you were playing with him. He'd go ‘G... A...’ And you were away.

“He also taught me... like, say you play a song five nights in one key, but on the sixth night the singer's throat ain't makin' it. You might have to go down a tone or so. George was really used to that, and he got me used to that.”

Instant transposition!

Young: “Right. And he was into some crazy things too, you know. Like he'd tell me the D string annoyed him. The G string too. ‘Too sweet for rock and roll,’ he'd say – so off went the G string! When I last saw him in the Easybeats, he had like four strings on that guitar. He was never a fan of light strings either – especially when those slinky strings came out. He'd say, ‘You can't tune 'em.’”

So now Malcolm uses real heavy gauge strings and you use lighter ones.

Young: “Well, Malcolm just seems to get heavier and heavier with his strings. Now he's at the point where they're not making that gauge any more, since the youth want them lighter and lighter. These days, you see, they all want to run from one end of the fretboard to the other. They want to practice their scales. I mean, that's all very good, so long as they do it at home.”

Why should we have to hear it?

Young: “Right.”

A lot of your greatest hooks are single-string riffs where you alternate between fretted notes and playing the string open – like Thunderstruck, for example.

Young: “Yeah, I was just fiddling with my left hand when I came up with that riff; I played it more by accident than anything. I thought, ‘Not bad,’ and put it on a tape. That's how me and Malcolm generally work. We put our ideas on a tape and play them for one another.

“Malcolm came in to see me once when we were on the Highway to Hell tour and said, ‘I've got this riff and it's driving me nuts.’ It's three o'clock in the morning and I'm trying to sleep, and he's saying, ‘Well, what do you think of this?’ I said, ‘It sounds fine to me.’ And that was Back in Black. Bang.”

So you like being in a band with your brother, then?

Young: “Well, it's good and bad. When I play something in the studio and the producer says, ‘Oh, that's great,’ I always look around and say, ‘Yeah, but what does Malcolm think?’ 'Cause Malcolm knows me, and if he says yay or nay, it's the difference between getting to go home or sitting in the studio all night.

“So, sometimes it's like having two producers. But that's good, because it keeps you on your toes. And if I really get disheartened, I can just hand Mal the guitar and say, ‘Here, you try it.’ Then he'll show me up and I'll say, ‘Right, I'll beat him.’”

What can you recall about your first tour of the States?

Young: “When we first came here, we toured around with a station wagon. We got put on with Kiss. This was when they had all the makeup and everything – the whole hype. They had everything behind them, the media, a huge show and stuff. And here we were – five migrants, little micro people.”

Johnson: “Migrant workers – that just about describes it! ‘Where's your green cards?’”

Young: “It was tough to even get into the show with that station wagon. Many a time they wouldn't let us in the venue 'cause they didn't see a limo. [Another nasal Yank accent] ‘Wheeahs duh limo? If yaw duh rock band, wheeahs yaw limo?’”

When was this?

Young: “1977 was the first time we got to America. So this would have been '78. It was pretty strange. I hadn't even heard of a lot of the music here at the time – I thought there would be more rock. But when we got here it was a disco-type thing.”

It was a dismal place in 1977.

Young: “What was real strange was that although the media was pushing this really soft music, you'd get amazing numbers of people turning out to hear the harder stuff. We were playing big stadiums and getting a great reaction.

“We'd be on the bill with a whole heap of acts – like in Oakland, playing a Bill Graham ‘Day on the Green’ event. We were on at 10:30 in the morning – the first act. But at 10:30 in the morning there were 65,000 people. And they knew what we were about when we came on. We were only on for 35 minutes. But in 35 minutes you had to do a lot. It was fun. It was exciting. I'd do it again.”

Johnson: “Yeah, yeah, that was excitin' times, that. Pick yer best and go out. Pow!”

Young: “Sometimes we could be real mercenary. Like if another band was givin' us a bit of stick – the headlining band or something. We get on and just sort of say, ‘Okay, we'll just turn up to 11 here, and let's go.’ Blow 'em away. We were good at that, too.”

Johnson: “Fuck 'em. Hah!”

Were you overwhelmed by the groupie scene here?

Young: “No, no, no, no, no. In those days, girls were only interested in... well, not us. You met more of that when you started in clubs and pubs. Because in that time, you got rich people coming to slum it, and other people coming to see what the fuss was about. So those were your times when you could meet more of the weird and wonderful women. The crazy people. But during those first tours in the States... no. No more than what would be now. Same thing.

“We were never that sort of band, anyway. I never ever saw a girl out there that would faint over me. Maybe she'd look and go, ‘Mmmm, I've never seen something as ugly as this!’ Maybe I'd get some of that. But not a – what would you call it? – a fan sort of thing.”

Johnson: “The Top of the Pops syndrome.”

Young: “But in a way that's always worked for us. You don't see an audience of young little girls screaming for us. So other people say, ‘Now that's a real band. That I like. It's real.’ 'Cause we aren't the prettiest things in the world. With AC/DC, it's not like we're here to steal your wife and your girlfriend and your daughter. We may borrow them, but...”

Johnson: “Only for a while.”

But don't girls like the schoolboy suit?

Young: “Well, they used to come out in England. But then, the English have been known for their craziness in the, um, sexual department.”

Johnson: “The public toilet department. ‘Vicar please, take yer hands off me. It's not yer turn!’”

Young: “I guess there's something a bit sexy in the blues element of what we do. That's probably more what's associated with the old strip club routine. I think that's somewhere in the back of people's heads when they hear that sort of music: the strip club image, you know? The smoke-filled room and the girl onstage. Well, I would like to believe that.”

Johnson: “I was startin' to feel good.”

One last thing: what's the origin of the schoolboy?

Young: “My sister. As a kid, I'd come right home from school and pick up my guitar, without changing out of my school suit. At dinner time, I'd still be in the school suit, playing away. My sister always remembered that. She thought it was cute.

“She was the one who said to Malcolm and me, ‘You know, it would be great if he'd get onstage with that school suit. It'll give people something to look at.’ I suppose she was right. At least it's worked for us.”

This interview was originally published in Guitar World magazine in 1992.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.