Abbey Road Engineer Ken Scott: Beatles' White Album Sessions Were a Blast

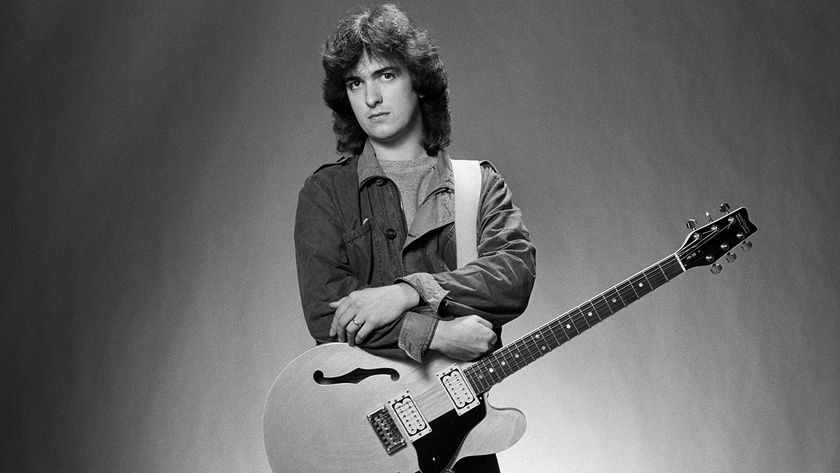

Ken Scott—one of only a handful of recording engineers to have worked side by side with the Beatles—has stories to tell. Good stories.

And lucky for us, he loves telling them.

To emphasize the point, Scott will be publishing a 500-page memoir, Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust: Off The Record with The Beatles, Bowie, Elton & So Much More, on June 6 through Alfred Music Publishing.

The book, which was co-written by Bobby Owsinski, recounts the many events of what Scott calls his "blessed life" working with innumerable rock legends. Scott began working in the tape library at London's Abbey Road Studios in 1963 at age 16. Abbey Road was a place where the Shadows, the Hollies and, most famously, the Beatles had already started making history.

Scott quickly segued into sound engineering at Abbey Road, eventually manning the board for several of the Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour sessions and creating mono and stereo mixes for the band.

But a pivotal moment came when he replaced Geoff Emerick in the engineer's seat during the 1968 sessions for The Beatles, better known as the White Album. Besides witnessing the band at their post-psychedelic creative high point, Scott was instrumental in helping the Beatles shift from four-track to eight-track recording. Scott also debunks the myth that the White Album sessions were miserable.

"We had a blast," he says. "Those other stories are bullshit." Scott went on to engineer and produce (often at the same time) singles and albums by scores of other artists, including George Harrison, John Lennon, Ringo Starr, David Bowie, Jeff Beck, Stanley Clarke, Dixie Dregs, Lou Reed, Elton John, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Devo, Kansas, Supertramp, Elton John and others.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

For a selected discography, see the photo gallery below. This is part three of our interview with Scott. Scott discusses working with David Bowie and Mick Ronson here and recording Jeff Beck here.

Below, Scott discusses recording sessions for the White Album and mixing sessions for George Harrison's All Things Must Pass album. He also offers advice to new bands that haven't quite reached the Beatles' status just yet.

So many people cling to the image of the Beatles constantly being at each other's throats during the recording of the White Album in 1968. How much of that is true?

It’s very heavily disputed in the book—the myth about how bad the feelings were during the White Album. We had a blast doing it. This was a six-month project, almost. And I haven’t done a project, even a two-week one, where someone hasn’t lost their temper at some point. They’re artists; they’re touchy at times. Obviously, if it happens during a two-week project, it’s gonna happen more frequently during an almost-six-month project. But it wasn’t like that the entire time. It was fun, we had a blast.

I did an interview for the book with Chris Thomas, George Martin’s assistant, and at the end, I used the same question I’ve been asked every time I’m interviewed: "Is there anything you’d like to say that I haven’t asked you?" Chris said, “Yes, please let everyone know we had a blast. It was fun. They were great to work with.” I’ve spoken to other people from the sessions, and we all agreed. We had a blast. So those other stories are all bullshit.

How about the mood when you were working on George Harrison's All Things Must Pass album in 1970? That's perceived as a very liberating time for Harrison.

Well, the basic tracks had already been cut by Phil Spector and [engineer] Phil McDonald. Then George decided he needed 16 tracks, which Abbey Road Studio didn’t have at the time, so George came to Trident [Studios in London] and worked with me for the overdubs.

During the overdubs, Phil Spector wasn’t around. It was George and I—and it was great. Once again, we got along like a house on fire. He was always in great spirits. When mixing, generally, it was very good spirits. That’s when Phil Spector came by again. George and I would start 2:30-ish in the afternoon and get the mix to where we were relatively happy with it, and then Phil would come in around 7 p.m., pass along his comments, we’d change some stuff, not change others. There were times when Phil came in when it could get a little edgy. Maybe George wouldn’t like his ideas or something, but it never got out of hand.

Then Phil would go and we’d continue to get the mix the way we ended up liking it. George would leave, I’d strip it all down and set it up for the next day, then we'd start all over again. Once again, it was a lot of fun, just with a couple of testy moments.

While making the White Album, had George developed into more of a leader and decision maker in the studio, like John Lennon and Paul McCartney?

Absolutely—but they all were. When laying down basic tracks, there was that whole collaborative effort. They were the old band—having fun in the studio. They kept on playing and playing and enjoying themselves altogether. But then when it moved to overdubs, a song became more of the songwriter's song, and often you wouldn't see any other member of the band besides the writer of the song you were working on at that time.

So different sessions were going on at the same time, like when Paul and Ringo went off to record "Why Don't We Do It In the Road" by themselves?

Yes, because there was so much material, and, for almost the first time since they'd stopped touring, they were under time pressure because the White Album was the first release on their own label [Apple Records]. Everything was set up for a very precise date; we had to be finished by this date to get the album out. So we tended to use different studios. I would be in, say, Number Two with George mixing "Savoy Truffle," and "Why Don't We Do It In the Road" was recorded in Number Three by Ken Townsend, one of the maintenance engineers. The last 24 hours when working on that album—we were using every room we possibly could. It was very strange [Laughs].

What can you tell me about the session for "While My Guitar Gently Weeps," when Eric Clapton came in to play the guitar solo?

That's a question I'm asked so frequently, and I have absolutely no recollection of it whatsoever. For the book, I wanted to try and get back to that session because I know it's a very important session and a lot of people are interested in it. I actually tried regression therapy to take me back, and, unfortunately, it didn't work [laughs]. I still have no memory of that session.

Given the song's heaviness, was there anything special about the “Helter Skelter” session?

Not much different—they just played a lot louder than usual.

What about “Yer Blues”?

That was different. We were doing a vocal with George Harrison on a track that turned up not being used on the album, a track called “Not Guilty” [which surfaced on Harrison's self-titled 1979 album]. George was having difficulty getting into doing the vocal, so we were trying various things, some of which were fairly madcap. At one point during the playback, I stood up, and I was standing next to John, and there was this little room outside of Number Two control room where one of the Telefunken four-track machines was. Originally with EMI they only had two four-tracks.

These particular four-tracks were really large, so they kept them in two small rooms, both next door to Number Two control room. And they could be plugged into any of the studios. By now we’d moved to Studer four-tracks, which were in the control rooms, so these two rooms were empty. So I stood up next to John, and as a joke, I said, “God, the way you guys are going, you’re gonna want to record in there now," pointing to one of these two rooms. John just sort of looked over there and didn’t say anything. A little later on we were gonna start a new song called “Yer Blues,” and John turns around and says, “I wanna record it in there,” and he points to the room I’d been joking about.

We had to fit them into this ridiculously small room. If one of them had suddenly swung his guitar around, he would’ve hit someone in the head. It was all so close to each other. But for me, I think the drum sound on that is the best on the album. I love that drum sound. And just the whole thing. There was no separation between anyone, really. So you had to just sort of get the mix as best you could—because everything was on everything. You had to meld it all together. I think John even did the vocal live. We had to; somehow we screwed up on the second half and there was leakage.

So redoing the vocal immediately changed the sound. But John being how he was, said, "Well, if we’re going to change the sound, we might was well completely change the sound"—and you can hear in the middle of it—the sound on the vocal completely changes. That was part necessity and part John saying, "Well, let’s go mad on it."

Did you do the mono mixes for Magical Mystery Tour and the White Album? And why are the mono and stereo mixes so different?

Absolutely. Normally we went to mono first. Up until the White Album, they had never been interested in stereo. But they became interested around that time. Paul told me they wanted to make the stereo mixes different from the mono mixes because they’d started to get fan mail about how people were buying both the mono and stereo mixes.

Fans were sending The Beatles letters, telling them how the mixes were different. So they realized this was a good way of selling double the amount of albums. So we had to actually make stereo mixes that were different. Up until the White Album, the stereo mixes were throwaways. England just wasn’t interested in stereo mixes. So they were done a little later, and we didn’t take massive amounts of notes. So if something was sped up, no one actually kept a note on how much it was sped up. It was just, “Oh, just speed it up a bit.” They were just thrown together, really.

How were Ringo’s drums recorded?

There really wasn’t a standard way. They were so experimental, they wanted to try different things all the time. There were a number of occasions when I’d go into the microphone room with Paul, and he’d just be looking around and say, “That one looks good. Let’s try it.” It didn’t matter what it sounded like. It looked cool, so he wanted to try it. But there were some fairly standard things. I think it was a [AKG] D20 on the bass drum and generally [AKG] D19Cs on the toms. The overheads would tend to change from ribbon to condenser. The snare was a Neumann KM56. That would be how we’d start, but we’d change mid-session.

And what's your go-to microphone choice for guitars?

I like to use a Neumann UM87 about a foot away from the cabinet. For distant microphones, it’s whatever happens to be there.

Would you say the Beatles were underrated as musicians?

That's so hard because you have to define what you mean by a great musician. There’s the technical kind, for instance, and they weren’t, in the slightest, technically minded. They learned by playing things and didn’t have the rules that someone who’s been schooled has. And that’s what led to a lot of their greatness, because they had no fear of doing strange things—putting certain chords after other chords, for instance. There were no rules for them. So in that respect, they were great musicians and probably were underestimated. But as technical players, no, they were OK. They were good. Certainly not the greatest.

What advice do you have for young, up-and-coming bands entering the studio for the first time? Is there any sort of checklist they can use?

Have good songs, have talent [laughs]. Oh, you mean other than those things? For the drummer, know your instrument. Know how to tune it. As far as guitars, I’m not a fan of modern guitars and modern pickups. There’s too much these days with pickups, everyone’s trying to get them as quiet as possible. In doing that, I think a lot of the tone is being lost. I’d rather have an old guitar that hums like mad or gives a lot of hiss or something, but you get great tone out of it. Because once you put the guitar in with the rest of the instruments, you don’t notice the hum or the hiss. You notice the guitar part.

So if you have the opportunity to use older guitars, do it. Also, know what you’re going for and don’t let others push you in directions you’re not prepared to go in. There’s a tendency with labels and A&R guys, especially with the speed with which they change labels where you sign with one A&R guy and halfway through a project, they leave and someone else comes in, and they have totally different ideas. You have to sink or swim by your own artistic temperament. Try not to be swayed, because it will become a mess.

Do you prefer analog or digital?

I like both. Whenever possible, I will use both. I will record basic tracks on analog, put it over onto digital. They both have their good points, they both have their bad points. I’m not a fan of the digital sound, I much prefer analog, but there are things you can do in digital that you can’t do in analog. But in using digital, be careful of plug-ins. I’ve seen so many mixes where every track will have 10 different plug-ins. If you have a great sound in the studio, you don’t need all of those plug-ins. It really bothers me hearing stories about, “Yeah, it’s good enough, we can mess with it in the control room.” Get the sound and the performance in the studio. That’s where it all starts.

For more about Ken Scott's new book, Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust: Off The Record with The Beatles, Bowie, Elton & So Much More, click here or check it out at Amazon.com.

Damian is Editor-in-Chief of Guitar World magazine. In past lives, he was GW’s managing editor and online managing editor. He's written liner notes for major-label releases, including Stevie Ray Vaughan's 'The Complete Epic Recordings Collection' (Sony Legacy) and has interviewed everyone from Yngwie Malmsteen to Kevin Bacon (with a few memorable Eric Clapton chats thrown into the mix). Damian, a former member of Brooklyn's The Gas House Gorillas, was the sole guitarist in Mister Neutron, a trio that toured the U.S. and released three albums. He now plays in two NYC-area bands.

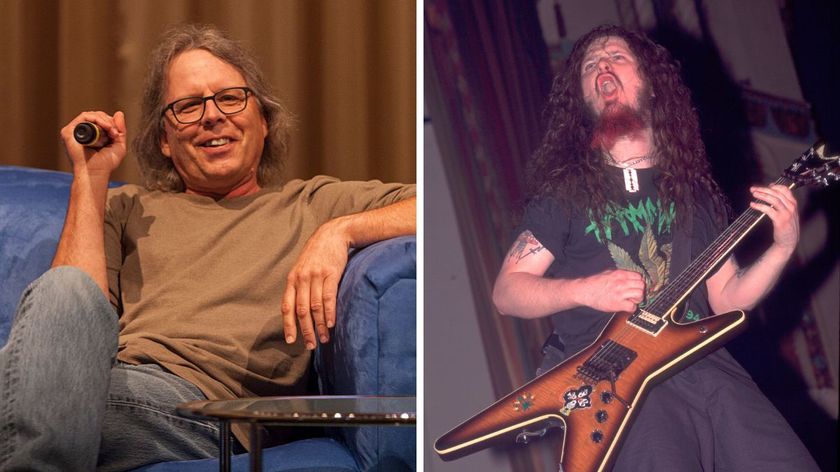

![[Left] Acclaimed producer Terry Date reclines on a blue couch as he speaks at an industry convention; [right] The late Pantera guitarist Dimebag Darrell, holds a note and feels it. He is wearing a white Garth Brooks T-shirt and plays his blue lightning finish Dean ML electric guitar.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nCqZukJJJMwpDY4ZeZhtsL-840-80.jpg)

“Around Vulgar, he would get frustrated with me because I couldn’t keep up with what he was doing, guitar-wise – Dime was so far beyond me musically”: Pantera producer Terry Date on how he captured Dimebag Darrell’s lightning in a bottle in the studio

“He ran home and came back with a grocery sack full of old, rusty pedals he had lying around his mom’s house”: Terry Date recalls Dimebag Darrell’s unconventional approach to tone in the studio