You might not know the names Kenny Greenberg, Russ Pahl and Derek Wells, but if you’ve been anywhere near a radio - particularly one tuned to a country music station - sometime during the past 30 years, you’re probably familiar with their work.

The three are considered among the upper-crust of Nashville’s first-call session guitarists, and even a cursory view at their combined (and sometimes shared) credits is nothing short of breathtaking: Taylor Swift, Kacey Musgraves, Blake Shelton, Toby Keith, Jewel, Kenny Chesney, Garth Brooks, Faith Hill, Tim McGraw, Eric Church, Miranda Lambert, Florida Georgia Line. And that’s just to name but a few people.

“It would be an understatement to say Nashville is the place to be if you make music,” Greenberg says.

It’s kind of funny how a lot of rock guitarists have moved here and found work in the country market. Country is so diverse these days

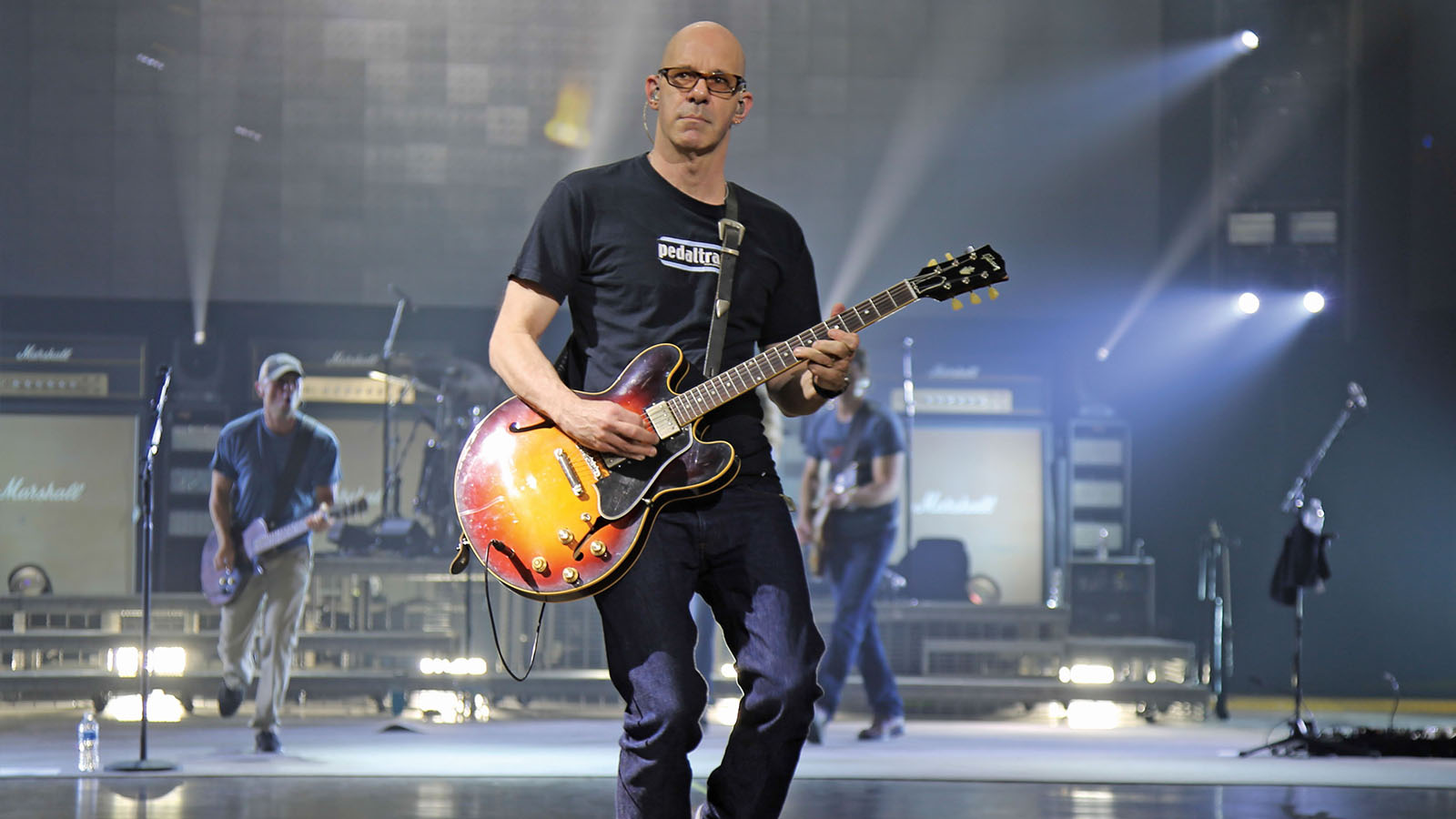

Kenny Greenberg

Originally from Ohio, Greenberg cut his teeth playing in high school rock bands in Louisville, Kentucky (“I was way into Hendrix and the Stones”), before moving to Nashville and entering the studio scene at 21.

“It’s kind of funny how a lot of rock guitarists have moved here and found work in the country market. Country is so diverse these days; there’s still traditional country, but there’s underground country, outlaw country, alternative country, the East Nashville Americana scene, the Christian music scene. It’s pretty wide open.”

Hailing from Minneapolis, Pahl is a 30-year veteran of the Nashville scene. His non-traditional - and now signature - approach to the pedal steel guitar (heavy on effects and atmospherics) has been featured on numerous Number 1 country hits, and over the past few years he’s enjoyed a steady collaboration with one of the town’s recent transplants, Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys.

“It’s always exciting when somebody new comes here and shakes things up a bit,” he says, “and I’m always looking to get in a room with them to see what we can do.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Noting that Nashville hasn’t been inured to the changing economics that have affected the entire music business, Pahl says, “Things have tightened up a bit. Fifteen years ago, labels were throwing crazy money around and there were huge budgets. Now people tend to be a little more thoughtful in how they make records. People do remote recording when they’re not in the big studios.”

Even so, he observes that there’s still enough work to go around for the established pros, and there are always a few slots available for newbies - provided they possess the right skill set.

“It’s just a given that you’ve got to be able to play,” he says. “And when I say ‘play,’ I mean you’ve got to be able to come up with the right parts that work on songs. Time is money, so you have to listen to the music and what the other people are doing. You have to be malleable and be a people-pleaser.”

Being a people-pleaser is second nature to Nashville-native Wells, the relative “new kid on the block”. While his versatile chops have pushed him toward the front of the line of Music City guitarists, he credits his parents with instilling in him the sensibilities to navigate the business and social aspects of the music-making community.

Nashville is a big town, but it’s also a small town that’s built on relationships. The bottom line is, you have to have the proper attitude

Derek Wells

“I knew early on that this is a competitive town and that you had to conduct yourself a certain way to be able to make it,” he says.

“Nashville is a big town, but it’s also a small town that’s built on relationships. The bottom line is, you have to have the proper attitude. This is a service industry, and you have to strive to meet the needs of your clients. Guitarists by nature can be a little egotistical, but that just doesn’t work here.”

As part of that proper attitude, Pahl stresses that any guitarist looking to find employment as a Nashville session player should also pack another essential attribute: an extra-thick skin.

“Nobody makes it right away,” he says. “You might be the best guitarist in the world - and yeah, we’ve got ’em - but you’re going to hear ‘no’ a lot. You need to get yourself out there and be seen. Play anywhere you can. All it takes is one break to get your foot in the door, but it’ll never come when you want it. It’ll come when somebody wants you.”

I’m sure your stories are all pretty different. How exactly did you get started playing sessions in town?

Kenny Greenberg: "For me, it was through mainly songwriting demos. I was playing in bands and was outside of the whole scene.

I started producing bands and artists, and people would be like, 'Who’s that playing guitar?' So in a way, I didn’t go out and find the work; it found me

Kenny Greenberg

"One day, a songwriter asked me to play on his demos, and after that I started getting calls from other people who had heard what I’d done. They wanted me to play on their stuff, too.

"After that, I started producing bands and artists, and the same thing happened: People would be like, 'Who’s that playing guitar?' So in a way, I didn’t go out and find the work; it found me."

Derek Wells: "Although my parents were in the business, they didn’t fling doors open for me. It doesn’t work like that; you’ve got to prove yourself.

"I did an audition for Josh Turner and got the gig. I toured with him for five years, which was cool, but I really wanted to be a session guy. Like Kenny, I came into it by playing on song demos. Once you start playing on people’s songs, things kind of fan out from there. People go, 'Hey, I like that guitar playing. Who is that?'"

Russ Pahl: "Same as Kenny and Derek, it was the songwriters who got me going. I came down here in the mid-'80s from Minneapolis. I dragged my stuff from club to club, sitting in wherever I could. Sometimes I got to play my own set; I’d do that for an hour, and then I’d move to the next club.

"Finally, I got a couple of road jobs, and that was OK till I started a family. I wanted to stay home more. That’s when I really started to get to know songwriters. Once I began to play on publishing demos, things really took off for me."

What were some of the hardest lessons you had to learn on your own way up the ladder?

Greenberg: "Learning how to play rhythm on an acoustic. I was busy doing solos all the time, but I didn’t have my rhythm and acoustic chops together. Once a producer told me to leave a lesson and not come back until I could play rhythm on an acoustic. So I had to sit down and teach myself. It was embarrassing at first, but I’m glad I did it."

Pahl: "For me, the mistake was trying to play like other people. I was playing steel guitar among the best players in the world. They did what they did better than anybody, but they were playing 'normal' steel guitar. So I had to stand out. The only way I could do that was to create my own language, learning how to use delays and make up new sounds.

"At first, I got my hands slapped - “That’s too different! That’s so weird!” Pretty soon, people started calling me up: “Hey, we kind of like that thing you’re doing. Can you do that on our record?”

Wells: "The hardest lesson was one I had to teach myself: how to be patient. At first, I was really eager to prove myself. Being the new guy, I would go to sessions all amped up: 'Don’t mess up. Do a good job.' It took me a while to calm down and enjoy the process. Once I did that, when I realized I had earned my spot, I had more fun just making music - and my playing improved. So I had to get out of the way of myself a bit."

In the 1960s, Los Angeles had the famed Wrecking Crew group of studio players. Does anything like that exist in Nashville?

Most of the music on the radio is played by the same 30 guys. There’s three or four drummers, two or three bass players, three or four keyboard guys, and the rest are guitarists

Derek Wells

Wells: "It’s kind of that same thing here in that most of the music on the radio is played by the same 30 guys. In that group of 30, I’d say there’s three or four drummers, two or three bass players, three or four keyboard guys, and the rest are guitarists and other players.

"While we don’t necessarily see the same guys five days a week, or it’s not just one crew that gets booked as a band, the number of guys at the top of the heap, so to speak, is small enough that if I go two weeks without seeing one of the same four drummers it’s pretty shocking."

Pahl: "It kind of revolves around the producers. Different producers have different groups of people they like to use. I’ve sort of had a Wrecking Crew thing with Dan Auerbach. He’s put together a group of seasoned older fellas. We cut whole records with him every five or six weeks. It’s great. We have a lot of fun."

In your opinion, what are some of the leading studios to work at these days?

Greenberg: "If you’re playing with a band, then Sound Emporium is great. There’s also Blackbird and Ocean Way. Those are the big three - there used to be 10. There are rooms at Sound Stage that are really good… Nick Raskulinecz moved into Ronnie Millsap’s old room there."

Wells: "Blackbird is incredible on every level. The facility itself is great, the staff are great, and the gear and rental department are unmatched. Ocean Way is an amazing facility. It’s one of the few rooms where you feel like the room itself has a sound. Sound Emporium is super, and so is Sound Stage."

Pahl: "I would name the same studios as the other guys, but I’ll also mention Dan Auerbach’s studio, Easy Eye. It’s a really nice place, and he’s got a bunch of cool gear."

Tighter budgets are now the norm throughout the music business. How has that affected the amount of work that’s available?

Greenberg: "I do less stuff in big studios and more tracks in people’s houses. It would be ridiculous to say that’s a good thing, but at the same time I enjoy taking one amp and a few essentials in my car.

"I’ll go over to somebody’s place and lay stuff down in their home studio. I pared down my gear, and now I find that I take less stuff with me when I go to work at big studios."

Pahl: "Sadly, what got us all started - working on song demos - has kind of crumbled. So now I’m doing a lot of custom records and vanity projects. You have to kind of spread yourself out more. There’s less work, but it’s enough to keep us going. The big guys who made their names get the calls."

In general, how many sessions do you play in a week? Is there a minimum/maximum you try to shoot for?

Wells: "Sessions are booked in three-hour blocks, starting at 10 in the morning till 9 at night. Some days you might work on an album and all three sessions are at the same studio. Some days you might have three sessions in three different locations.

"When I was hitting it really hard, I was doing three sessions a day, six days a week. That was clearly not sustainable, but that period of going hard made me a better session musician at an exponential rate. These days, I’m a little more selective about when and who I work with."

Pahl: "If you can get five to 10 sessions a week, you’re rockin’. Ideally, I would like to work two three-hour sessions five days a week, but it’s usually more lopsided than that."

Greenberg: "It changes every week for me. I don’t shoot for a minimum or maximum; it can be anywhere from two or three sessions, but sometimes it’s 10. Probably half of my sideman work is doing overdubs for people at my place, and the other half is going to studios in town."

Speaking of remote recording, is there a different way you approach tracks when working on them at home versus recording with a producer in a studio?

When you’re in a big studio and the clock is running, you try to nail things quickly because you have to. At home you can waste a lot of time screwing around

Kenny Greenberg

Greenberg: "You have more freedom when you’re working on stuff at home. I usually give people a bunch of different passes, and they can choose what they want. Sometimes people are very specific about what they want, but other times you can do what you like till you see what works.

"It’s kind of funny, though. When you’re in a big studio and the clock is running, you try to nail things quickly because you have to. At home you can waste a lot of time screwing around."

Pahl: "I did remote recording intensely for about 20 years; I was one of the pioneers in that area. But I quit doing it two or three years ago. I just got tired of wrestling with computers, and I was bored with playing by myself. I like to be in a room with other musicians."

In terms of getting hired, is it better to be a specialist or a jack of all trades?

Greenberg: "I think it’s good to be a jack of all trades. There are exceptions, but in general what people look for is someone who is versatile. Russ is kind of in a league all his own because he reinvented steel guitar. He came up with his own language for it, and now it’s something everybody speaks."

Wells: "I’ll say the same about Russ: He’s his own guy and he’s created his own world. If you want what Russ does, you call him; you don’t call anybody else.

"In terms of specialist or jack of all trades, there’s merits to both: for me, I try to be a chameleon. I’m going to show up and I’m going to do what’s right for this record, no matter what. I pride myself on the idea of being able to be thrown into just about any kind of musical situation and not be the wrong guy in the band."

Pahl: "OK, now I’ll throw some compliments back at them - I remember seeing Kenny 30 years ago playing in a blues band, and he scared me. He looked like a tough guy, but then I found out that he’s a gentle soul and very sensitive musically. He really listens to music and searches for that right part. He’s a beautiful musician who gets very involved in what he’s doing.

"And young Derek is a second-generation session guy who grew up in it. I’ve known him since he was young, and I’m just amazed at his depth of knowledge and skill. He’s the consummate pro guitar player, so it’s no wonder everybody’s calling him.

"As for myself, like they said, I do a specialty thing, but I also have other unique aspects to my playing. I can do a thing on gut strings that no one else does. I have a whole vocabulary of wah-wah things and delay sounds that I pull out. I also like to work with 12-string guitars. There are thousands of things you can do if you put in the time."

What were the most challenging or the strangest sessions you’ve ever been a part of?

Greenberg: "I don’t know if I’ve had a really weird session, but I’ve been on some that didn’t go as planned. I mean, we all get replaced - it happens to everybody. You’ll play something and the producer will go, 'We need something different.' So they call up somebody else. I’ve also been the guy replacing somebody. They’ll play me a part and say, 'Can you make it better?' That’s happened a ton of times. It’s just part of making music."

Wells: "I had a weird experience when I was I was flown out to LA to do a session, but it turned out they had the wrong guy. They wanted Eric Walls, who’s played with Beyoncé and other people. So I flew back without playing a note.

"In terms of getting replaced, sure, that happens both ways. Or sometimes they try to squeeze one last track in at the end of the day, but everybody is shot and wanting to get out the door. Or maybe you’re trying to get to your next session and they’re wanting to keep you. Other times you find out that you’re hired because their first choice wasn’t available. You just have to roll with the punches.

I never want to be the wrong guy in the band. You wouldn’t show up for a metal gig with a Tele and a Tweed, and you don’t show up for a country gig with a Les Paul and a Marshall

Derek Wells

Pahl: "Once in a while you do a session where they want you to do stuff that just isn’t you. And no matter how versatile you are, you’re just not the right guy for the job. Sometimes it’s just personalities or how the producers are feeling that day. Sometimes you can’t explain why something isn’t clicking.

"Like Kenny and Derek, I’ve been on both sides of being replaced. You have to develop a thick skin to do this, and you can’t argue with the producers or artists. It’s funny: I’ve played on sessions, and then I’ll hear the track on the radio and I’ll go, 'Hey, that’s not me. They must have gotten somebody else.' At first, it’s painful, but you can’t lose sleep over it, ’cause then you hear your playing on another song and it’s everything you did.

Generally speaking, what kinds of guitars and gear do you always bring with you to a session?

Greenberg: "I always have a Tweed Deluxe and a Mark Sampson-era Matchless. For guitars, I’ll bring a humbucker guitar, like a Les Paul or a 335. And I really like what Russ Pahl does with Strats - he winds his own pickups.

"I might also bring a Tele with a B-bender, an electric 12-string and a baritone guitar. And I’ll bring a big-bodied Gretsch or something similar. I can fit all of that in my car, and I’m good to go."

Wells: I try to cast myself for a session: 'OK, today I’m playing for Kenny Chesney. What does that look like for me?' I never want to be the wrong guy in the band. You wouldn’t show up for a metal gig with a Tele and a Tweed, and you don’t show up for a country gig with a Les Paul and a Marshall.

"So I’ll ask questions beforehand: 'Are we rocking, or it this more traditional country?' That gives me an idea of the gear I need. I’ve got a stable of guitars and amps and cabinets, but I try to find out first what’s required."

Pahl: "I usually bring a Fender Princeton amp. That’s all I really need. I have a custom-made steel guitar that a friend of mine built. It’s called a Show Pro, and we designed it from the ground up. It’s longer scale, and I did all the wiring on it. I’ve got a pedalboard with all of my effects, and I can control them with pots that I have built into the guitar.

"I’ve also got a Telecaster and a 335. Then I’ve got a Strat and a Gretsch, and there’s an old Gibson J-50 acoustic.

"A lot of times, if I’m at a session with Kenny or Derek and I don’t have a particular guitar with me, I just borrow one of theirs. We’re all friends and we help one another out. That’s how it works around here."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“Every tour was the best I could have done. It was only after that I would listen to more Grateful Dead and realize I hadn’t come close”: John Mayer and Bob Weir reflect on 10 years of Dead & Company – and why the Sphere forced them to reassess everything

“Last time we were here, in ’89, we played with Slash on this stage. I don't remember what we did...” Slash makes surprise appearance at former Hanoi Rocks singer Michael Monroe's show at the Whisky a Go Go

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)