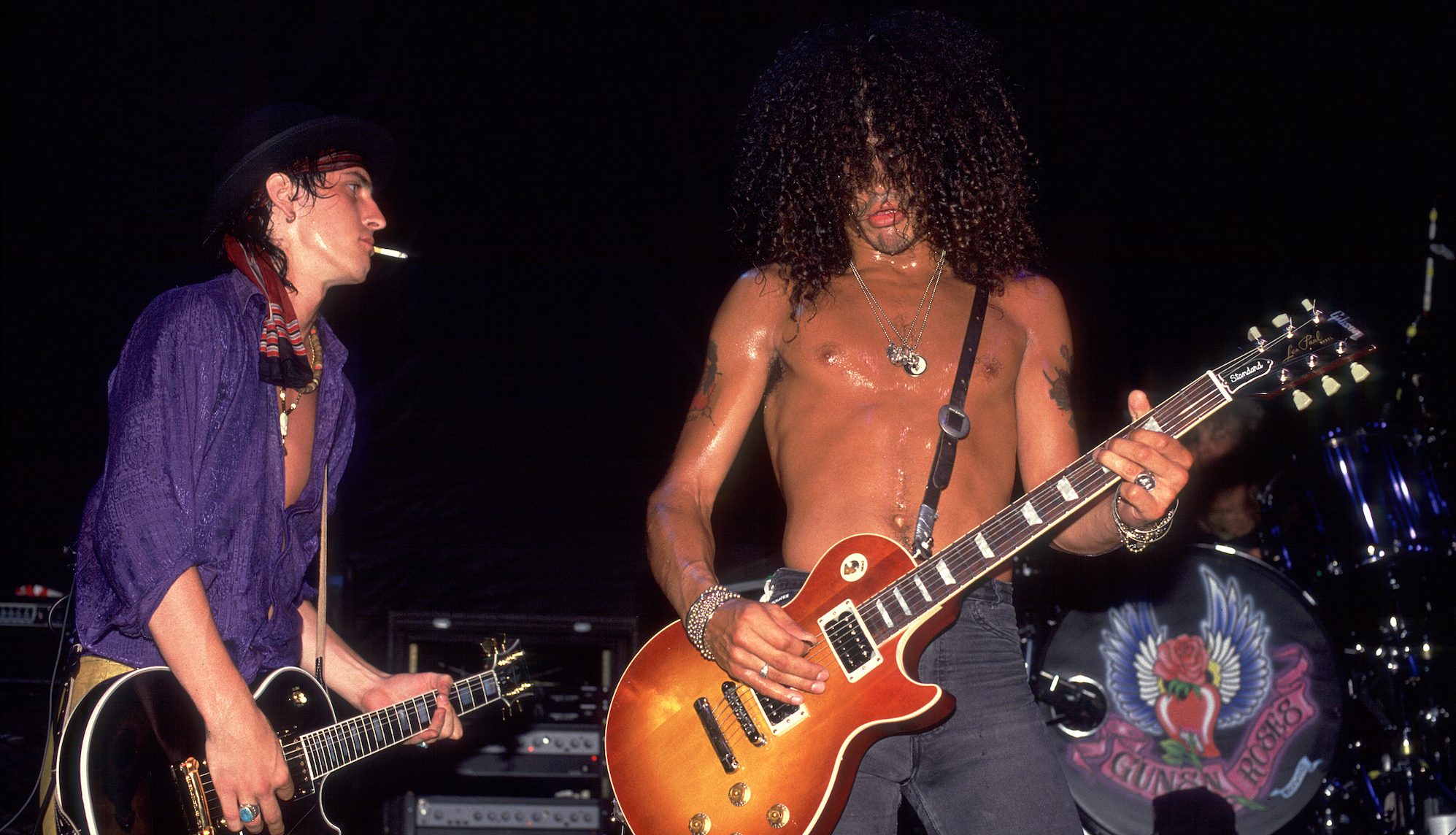

Guns N' Roses' Slash and Izzy Stradlin: "We wanted the necessary studio polish, but with the live, raw feeling intact"

Here's our interview with Slash and Izzy Stradlin of Guns N' Roses from the March 1989 issue of Guitar World. The original story, which started on page 50, ran with the headline, 'Raunchy Guitars and Reckless Reps.'

It's another perfect wreck of a Sunday afternoon in downtown Los Angeles. While thousands of dazed denizens attempt to piece together fragments of the previous night's misadventures for either themselves or some like-minded compatriots, the very object of many of their fantasies is polishing off his morning cocktail.

For the man known as Slash, Guns N' Roses' volatile, rakish lead guitarist, living the crude values extolled on the band's debut, Appetite For Destruction, has become something of a full-time occupation.

Sleep – an increasingly rare indulgence for Slash – is a welcome but impractical notion. In just a few hours, Guns N' Roses are due to convene their first rehearsal in a month, in preparation for their maiden voyage to Japan. New Zealand will quickly follow.

And then there's the business of writing and recording the follow-up to Appetite For Destruction, the raging slab of backstreet howls and disillusionment that came from nowhere and managed to sell over six million copies in the United States alone (ranking it behind Whitney Houston and Boston as the third largest-selling debut of all time).

"Yep, the pressure's kind of on," Slash admits sheepishly. "Still, it's nothing we can't handle. What I try and do is act as if nothing has really happened. So we sold a lot of records – big deal. It's not going to change the way we live or the way we try to make our music. Surface things will take a different course, sure, but the important thing for us is to just ignore it."

Slash's humble assertions notwithstanding, the fact is that indifference is something none of the members of Guns N' Roses appear particularly adept at. Pain and outrage have inspired some of rock 'n' roll's finest moments, from Elvis Presley right on through to the Sex Pistols.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In that spirit, Guns N' Roses' memory of a more squalid existence – at one point, the band shared guitarist Izzy Stradlin's ratty studio apartment, the band's members relegated to floor space – served as fuel for the dozen compositions that became Appetite For Destruction. Taken as a whole, the album is a beautiful mess: noisy, nasty and, at times, overtly brutal.

The roar of Les Pauls screaming through Marshalls (Slash's much-praised trademark sound) is nothing new, but the absolute conviction of execution, coupled with Izzy Stradlin's churning, Neil Young-style rhythm guitar, constitute a whole far greater than its parts.

All too often, the efforts of guitarists in search of "the big sound" result in nothing more than forced, croaking rumbles. Stradlin's and Slash's sound is authentically vicious – a reverent nod to the past and a watchful eye to the future.

There are some flabby spots. Some songs – You're Crazy and It's So Easy – seem dashed off and ready to collapse, while others – Out ta Get Me and Anything Goes – promise much but, ultimately, spin their wheels. But the core of the album – Welcome to the Jungle, Nightrain, Mr. Brownstone and Sweet Child o' Mine – are fully realized evocations of late-'80s excess and despair.

Not since the glory days of the Eagles (whose message, sadly; was lost on most party-hardy fans) have the woes of the modern-day desperado been so palpably rendered. The songs set a high standard for future band efforts.

Guns N' Roses' impact is manifest on the dozens of L.A. stages brimming with chest-pounding, bandana-wrapped posers who parade their "streetwise" selves. Ironically, the more these wanna-be's huff and puff, the more the public seems to respond to the band they perceive as the real thing.

"It could be said that we have a pretty nasty history," admits Stradlin. "The thing is, I don't give a fuck about the image that everyone buys. It's all been blown out of proportion, the 'bad-boy' thing, how much we drink, how much drugs we do or don't do. It's boring. While everyone's talkin' about what we did or supposedly did yesterday, we're already working today on the music they're gonna hear tomorrow.”

Slash, for his part, sees the humorous side: "The image tag is an easy thing to finger us on. None of us are model citizens, I guess. But the musical end of it can get funny. Why, I'm already hearing people pulling out those wah-wah pedals, slipping 'em onto tracks and subliminally sounding a lot like us. That's a compliment, but it's kind of missing the point, isn't it?"

Strap a guitar around Slash and an unbroken ribbon of riffs will inevitably flow. Not the phoney-baloney kind that routinely kick off most generic heavy rock excursions; but the classic, iron-fisted variety that assumes a front-and-center role in a song.

Born in England in 1965 and raised in California, Slash developed a keen musical ear early on. Since both his parents worked in the business, at-home listening was readily encouraged.

"This predates CDs or even cassettes," Slash recalls, "but we had something like a thousand records at home, all kinds of stuff. So, by the time I became interested in playing the guitar, I had a pretty acute sense of what I liked and why I liked it.

“That can be very important. I remember Jimmy Page saying once in an interview that the most essential element to being a good musician is being able to hear music in your head. If you can hear it, then you'll show yourself how to play it!"

A good theory, but rather difficult to test on the one-stringed Spanish guitar Slash started on. "Yeah, a lot of jumping around was required!" he laughs. "It wasn't a real bad guitar or anything, but it did have just one string – the low E string. I was real determined to learn, so just having a guitar was a start. I taught myself a bunch of songs on just that one string.

“Then, when I finally went for lessons, the teacher just sort of looked at me and asked if I had another guitar. I guess I was kinda naive back then. So, there was a long period before I had a real guitar."

By the time he owned his first authentic instrument, a Les Paul copy bestowed on him by a thoughtful grandmother, Slash was doggedly teaching himself licks off of records.

"It was," he remembers, "the only way that could have worked for me. I wasn't real good with the lessons, though the guy I did study with, Robert Wolin, was a big help. He was an inspiration, in a way, because he had a band, one of those really good Top Forty bands, the kind that played all the classics, night after night.

“He was literally the most amazing player I'd ever seen. He turned me on to what the difference was between lead and rhythm, showed me how to recognize and play the different things I was hearing on records. It was a lot of fun, really, because I'd bring him a record, he'd put it on, and he'd learn it right there, all the leads, everything note-for-note.

“When you're a teenager, the most amazing thing is seeing someone play Stairway To Heaven right in front of you. So this teacher gave me the basics in just the right way, which enabled me to take things off of records and learn 'em myself, which is what I did for a long time."

Growing increasingly obsessed with the guitar, Slash, an admitted "fuck-up" in school, practically ditched the entire seventh grade to sit home and practice.

"Your basic '70s rock fare," he recalls. "Zeppelin, Aerosmith, Ted Nugent. The guitar just held this unshakable thing for me. About the only thing that interested me in school was this music harmony course, which I took because it was music and I figured that I'd be interested in it.

"The whole course was based around the keyboard – everything was written on it. The interesting thing is that I got an A in the course, although I never really applied anything to the guitar. It didn't occur to me. The course, to me, was more mathematical.”

Slash's equipment collection then mirrored his somewhat haphazard approach to playing. "The amp I had at the time was a Fender Twin, a black-faced one. I didn't know what I was holding on to, so I traded it for this piece of shit, this Sunn Beta Lead! Can you imagine? It had this solid-state crap head, it was just the worst! Man!"

The Les Paul copy met with a more merciful fate: "I wound up putting it neck-first through a wall. I don't know why. I wasn't able to get instruments I liked until I started working in this music store; because of that job, I was able to get some good deals. I got a B.C. Rich, then a real nice '59 Stratocaster and then a '69 Les Paul Black Beauty, which I really liked."

By the time Slash started gigging, a genre-less void had developed on the Los Angeles club scene. The Knack explosion of 1979 evolved into a brief L.A. punk movement. However, it wasn't until a resurgence of heavy metal – a newer, flashier version, spearheaded by the likes of Mötley Crüe – that the Hollywood club scene finally got back in business.

Around this time, different factions of what eventually became Guns N' Roses started jamming together.

"There was Izzy and [vocalist] Axl," Slash recalls, "and then there was [drummer] Steven [Adler] and I. And then there was us in different combinations. We weren't ready, though, and it didn't last quite long." Dissatisfied with the lack of progress, Slash quit for a time, surprising everyone by joining a funk band.

“A real odd choice," he allows, "but definitely a good move. We didn't play many gigs – I think we played just one – but we jammed all the time. It really helped get my feel together, my sense of rhythm and overall approach. I'm really glad I did it. I feel it helped my attitude for when Guns N' Roses really happened."

"I was seventeen when I came out to California," Izzy Stradlin reminisces wearily. It is another early morning, too early, by most rock-star standards. Any broaching of his personal history elicits hardened, almost pained responses from the guitarist who, despite the early hour, insists on talking; he speaks in hushed, measured bursts, drifting off occasionally, as if at any moment he could lapse into a deep, powerful sleep.

Born in 1962 in Lafayette, Indiana, Izzy moved around as a child. "Family stuff," he snaps, without elaborating. "I grew up in Florida and moved with my mom to Lafayette. I started pissing around with a drum set, met Axl, and we hung out a lot. It was nowhere. We decided to put a band together.

"It was a bad time, being there. The people, the girls, it was so backward. The girls didn't even know how to dress when they went to gigs! So, the prospects were absolutely zilch.

“Axl and I were into anything that had a hard, loud beat. I think that's how we managed with all that was comin' down."

Packing his drums in the back of his Chevy Impala, 17-year-old Izzy decided to try his luck in California. The drums were quickly scrapped for a bass, which, in turn, was promptly exchanged for a guitar.

"It was a natural thing to do," he explains, "though I really can't explain why. The music I was into and wanted to play lent itself better to the guitar. I was always into hard stuff, the Ramones, the raw power that stuff had, the sound of the chords. So I got this Les Paul, which was real good for barre chords – all I could really play at the time, anyway. Then I got my friend's guitar, a Gibson LG5, I think. I'd play that guitar to Ramones records forever.

"Soon after that, I got my hands on a Gibson Black Beauty, which I had for years. Before we went out on tour last year, I had to pay the rent, so I offed it!"

By the time Guns N' Roses re-formed (with new member, bassist Duff McKagan), gigs and notoriety came much easier than before. After debuting their new act at the Troubadour, the band became fixtures on the Hollywood streets, playing any gig that came their way. To all appearances, they were just one more ragged bunch of losers, going nowhere fast. But, as Slash says, there was a method to their madness.

"We basically junked a lot of our lives at that point to work on the band, to work on the music. Sure, it might not have worked, but that was the chance we had to take. We didn't know any other way, nor were we particularly interested in any alternatives. I guess we were sort of... fearless."

Holed up in Izzy's one-room digs, the band eked out songs on whatever equipment they happened to own that week, viewing their desperate situation as necessary fodder for their compositions.

"Some of the best stuff can be written out of dire times," Izzy states matter-of-factly. "Slash and I would throw riffs back and forth, which is certainly one of his major strengths. I write on anything – I did then and I still do. I think I wrote much of the stuff on Appetite on an old Harmony. It was pretty hilarious.

"Stevie would set up this suitcase and drum on it. Pretty crude. I would tape-record the whole thing on this little micro-cassette recorder. It sounded real good; that's how we wrote. I think maybe one day I'll press that stuff. So it doesn't matter what you write on, PortaStudios, eight-tracks. If you have a song that can cut it, it doesn't matter."

By the time the band – renowned for its live following and uncanny ability to manipulate the L.A. press – signed with Geffen, the twin-guitar team of Slash and Izzy had developed into a pernicious, ferocious, aural assault squad, more reminiscent of the early Clash, Stooges or middle-period Stones than anything resembling heavy metal.

The lead-guitar duties, with rare exceptions, naturally fell on Slash, who had refined his technique over the years of bad gigs and endless rehearsals.

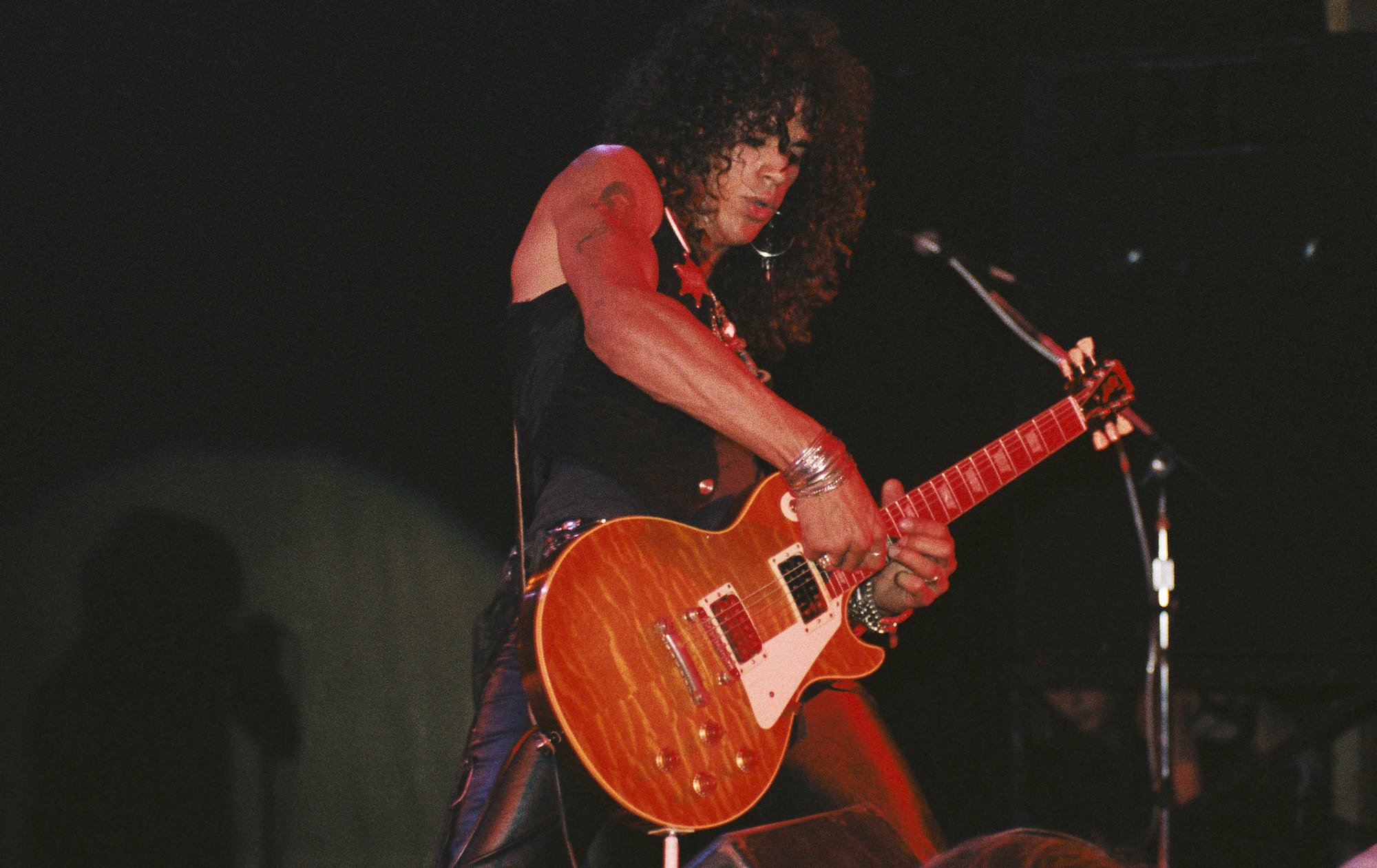

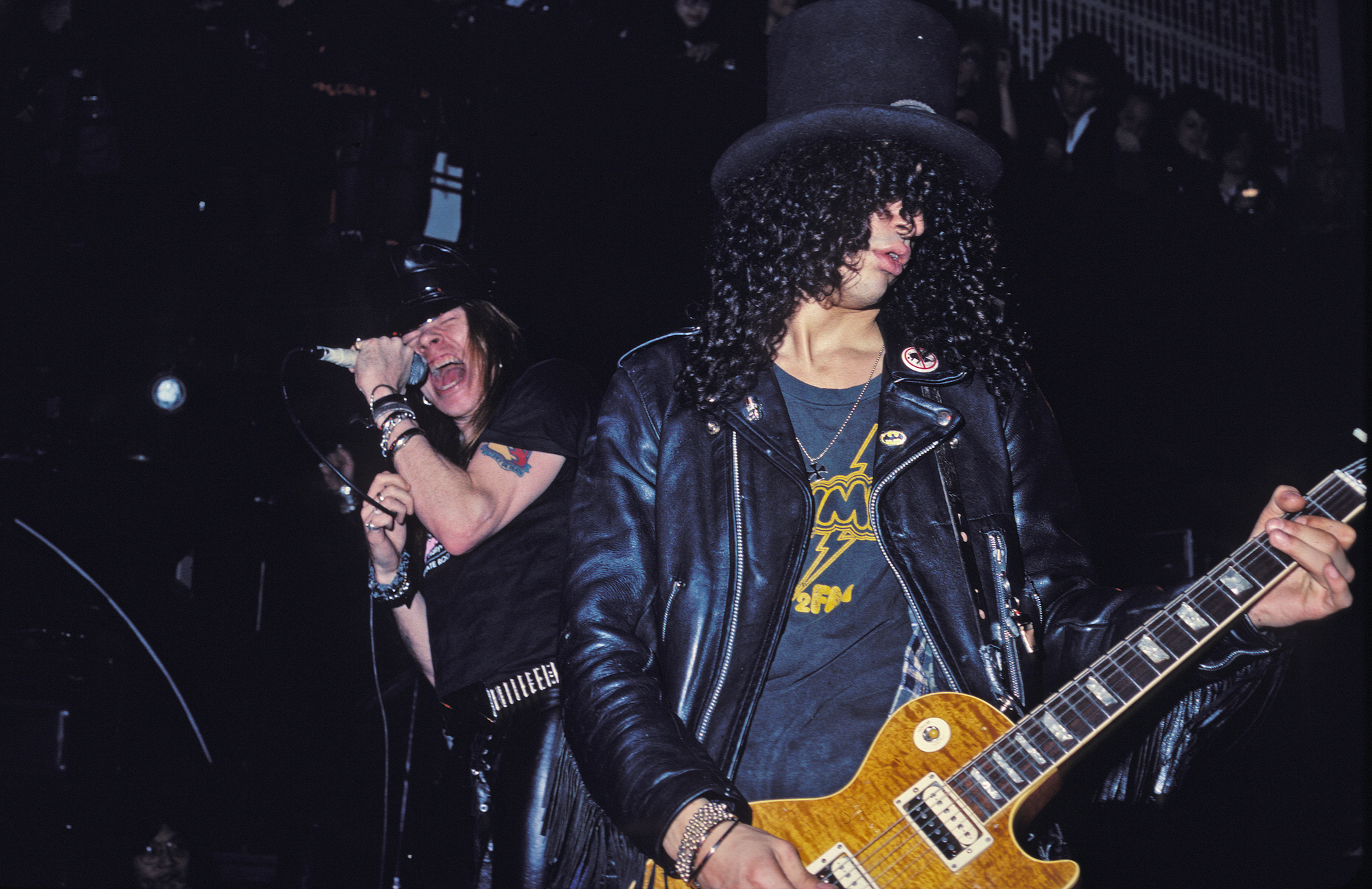

Next to Axl Rose, whose manic, incendiary vocals put him light years ahead of his hard-rock peers (this guy means it!), it is Slash, consistently outclassing his material (that's a compliment) with witty, multi-faceted solos and transitional lines, who gives Guns N' Roses their most unique, powerful and expressive voice.

While many contemporary players – the majority of them talented and blisteringly fast – approach an eight-bar solo by locking into a hand position and using that as a base for hammer-ons and pull-offs, concluding with a vibrato-arm dive-bomb or some other attention-grabbing gimmick, Slash appears to view such displays of facility as constricting.

“A lot of what I hear just isn't very musical," he explains. "It's not that I don't like playing fast, because I do. Especially if I've been playing rhythm for a while, because then I’ll be really itching to come out and lay one on the crowd.

"I know most chord voicings, doublestops, different ways around, and I don't like to get stuck in a rut. Because I don't usually write any complete songs – all the changes – it gives me a lot of room to see what's going to work when I take the song to Duff or the rest of the band. I'm usually the guy in the band who's going, 'Wait, guys, let me work this part out here in rehearsals.' It takes me a long time to come up with parts that I'm happy with.

“When I write a solo, I try to hear what I'm going to play first – that way I can usually weed out the bad ideas pretty quick. I see a lot of these guys who are in one hand position, and they'll be going as fast as they can. It's real impressive, but it doesn't sound very good."

The solo to Sweet Child o' Mine is a perfect case in point. Rather than come out swinging, Slash weaves the first half into a provocative, almost Spanish acoustic-sounding splash of neatly connected melodic ideas, before blasting into a frenzied wah-wah conclusion. It's a blur of lines, a bloodsquib that rises to the challenge of Axl's tragic, Romeo-and-Juliet-tinged lyrics. In short, a mini-masterpiece.

"I knew I had to come up with something good," Slash recalls, "because the chord changes were fairly simple and straightforward. I probably use the pickup switch more than anybody else I see, which is because I don't like to use effects, really, not even a boost. So for the first part of that, I was on the neck pickup, and then I clicked into the bridge position for the crazier part.

“The second part was an overdub, and you can hear the transition, the moment where the first half is ending and the second thought is coming in. I don't mind that – it's a record. Live, I have to approximate the second half without the wah-wah, because I don't go on stage with any effects at all – nothing – because I'd just wind up kicking everything off the stage anyway. So I just rip into it a little differently. I don't think anybody notices, especially in the clubs."

"That's the way we recorded the album, with that thought in mind. We wanted the necessary studio polish, but with the live, raw feeling intact. It's a tricky thing."

Producer Mike Clink allowed the band only two weeks to knock out the basic rhythm tracks, all of which were recorded with the band playing together in one room with minimal baffling. Izzy preferred to play on one of two tracks, favoring feel over any discernible flaws.

“You can hear Izzy on the left speaker," Slash notes, "and I went for a stereo mix. I did my rhythm tracks with the band, but all of my overdubs and leads I did by myself in the control room.

"A few of the solos I wrote right there on the spot. It had its advantages, of course, but the only drawback to recording like that is that I like to use a lot of feedback – live, I use it a lot – and because my amp was out there in the room and I was in the control room, separated from it, I couldn't work that out. I'd still like to record the next album in that way, but I'd like to work the feedback thing out too."

Outboard "sweetening" was kept to a minimum. "I don't generally like sounds that I can't get myself," Slash states firmly. "I like the wah-wah because, to me, it's a natural, workable sound effect that is very musical. It got a bad rap because so many people abused it.

"I like the tone that a wah-wah can produce, the way you can make it scream and cry. It sings. I don't like the sound of flangers, though, because it isn't very human or life-like. It's an automatic effect you can't control much. No matter what you do, it'll just repeat the same fluttering effect at whatever tempo you set it at."

On Anything Goes, Slash makes clever use of yet another attention-getting novelty item: the talk box. By trading phrases with guitar and talk box, he creates a mini-operatic effect, a call-and-response segment that is exhilarating, certainly the song's high point.

“Again, people associate the talk box with a lot of misuse, a lot of indulgence. Go back and listen to what Peter Frampton and [Jeff] Beck did with theirs. I got mine from a guy who used to play in a disco band!"

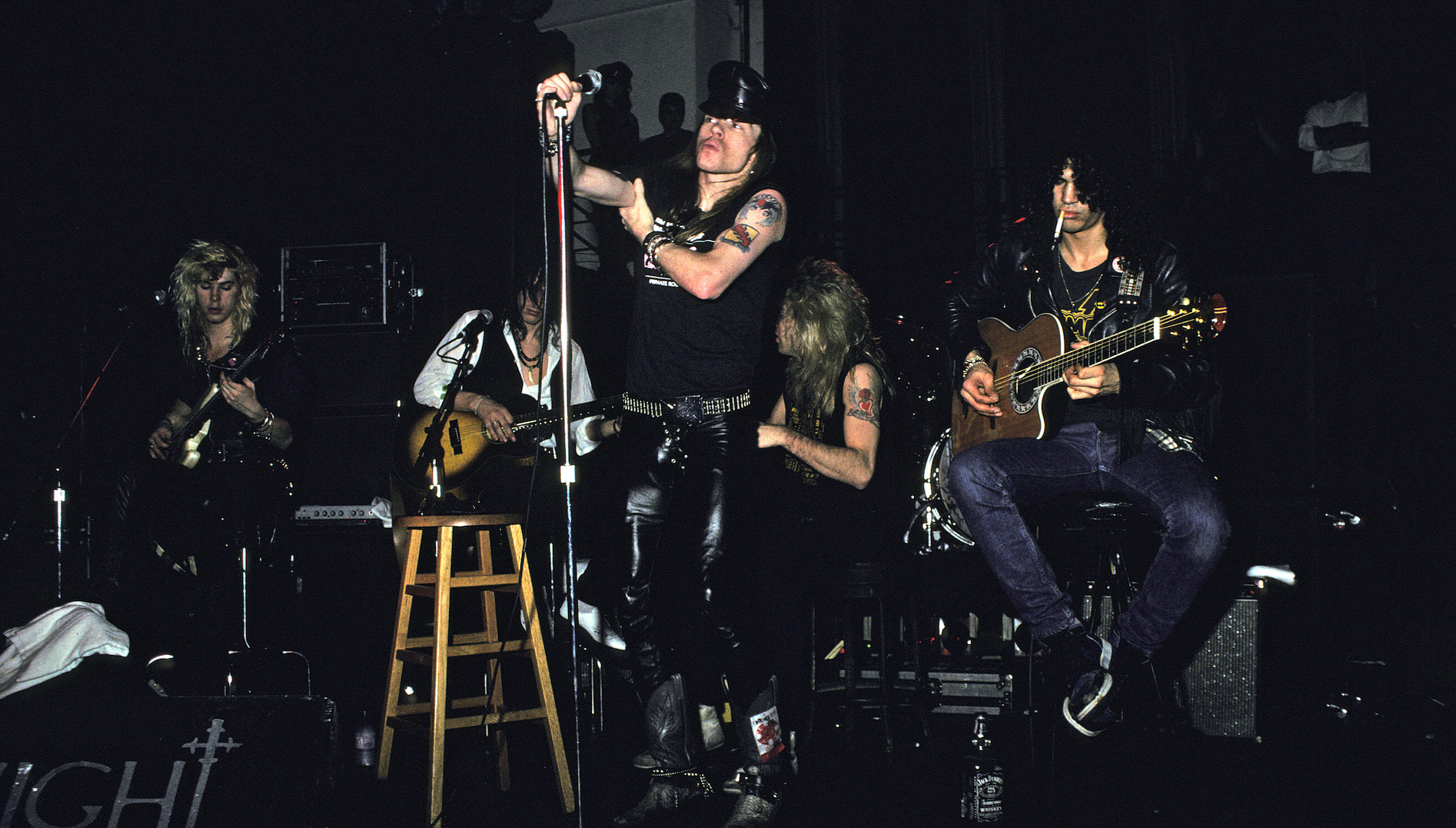

As accomplished as their first studio outing is, Guns N' Roses appear to be in their element on stage, where they duplicate their recorded sound with an almost eerie precision.

There are trouble spots – tempos speed up and slow down, sometimes breaking down completely; Slash, in particular, suffers at times from moments of over-enthusiastic audience participation: The solo to Out ta Get Me is resplendent with savage, atonal bends.

During a show at the Ritz in New York in early '88, a crazed female fan reached up and grabbed hold of Slash's guitar neck just as he was starting the solo, creating a spontaneous whammy effect. Oddly, it worked. “And it just happened to be captured on film too, 'cause MTV was taping the whole thing!"

Although audiences seem to revel in such moments of mayhem (and some fans seem all too willing to help the band push the panic button), the band generally gather themselves well. There is a sense of perpetual motion to the arrangements that is unbreakable.

In the manner of Aerosmith on their classic '70s releases (Toys In The Attic, Rocks), extended powerchording is kept to a minimum (Slash seems to eschew them altogether). Transitional phrases – verse into chorus, chorus into verse – are powered by Duff's sturdy bass-note runs, usually accompanied by Slash.

"Duff is a former guitarist," Slash notes. "That makes him real good with working out those parts. He thinks like a guitarist and won't just pump out quarternotes. Like those hidden bridges, the one in Welcome to the Jungle, that roving part – that's his specialty.

"I don't know if anything we write is visionary or anything. We just don't like to sound like other people. We're real conscious of that. We don't spend a lot of time worrying about airplay or song length, but we seem to be able to come up with accessible material anyway. Because everyone has a say in the songwriting and construction of the arrangements, songs come out pretty interesting by the time they're completed.

"No one has a final say, though the guy who wrote the bulk of the song can voice his opinions a little more strongly than the rest of the guys."

A Tascam eight-track recorder has been gathering dust in Slash's apartment for a short while. In his spare moments, he's been constructing riffs and song ideas in preparation for the follow-up to Appetite For Destruction.

"I know I should use the eight-track," he giggles, "or even my four-track. But the ghetto box I have is so much faster to get your ideas down. Real high-tech, right?"

To satiate fan interest while the band is ensconced in the recording studio, Geffen has released Live ?!'@ Like A Suicide, a live EP issued on the band's own Uzi/Suicide label before their major-label deal.

Only 25,000 units had originally been issued, making it quite the collector's item (it's been fetching upwards of $100 on the black market). Featuring a rollicking version of Mama Kin along with four new acoustic tracks (unheard as of this writing), the EP is firm evidence of a band fully in control of its own vision and destiny.

"We're a lot of things," Slash concludes. "Yeah, we live a lot of fantasies out, I suppose. But we're not the animals people make us out to be. I drink a lot, I guess, but never during a show. I'm not drunk onstage, much to the contrary of certain reports. I couldn't be.

"Afterwards, sure, the after-show festivities are kind of hard to turn down. But we're a lot more dedicated and smarter than a lot of the press would indicate. We couldn't have come this far otherwise."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“The Beyoncé effect is, in fact, real. I got a lot of traffic just from people checking the liner notes”: With three Grammy wins and plaudits from John Mayer, Justus West is one of modern session guitar’s MVPs – but it hasn’t been an easy ride

“You might laugh a little. The post office shipped your guitar to Jim Root”: This metal fan ordered a new guitar from Sweetwater – but it ended up with the Slipknot guitarist

![Guns & Roses [HD 1080p 16/9] : Rocket Queen - Live NYC (1988) - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/4D_C0mmOX-U/maxresdefault.jpg)

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)