“George asked, ‘Is it OK if I do a little slide?’ I had a ’63 Strat, and that’s what he used. He was one of the best slide players ever”: They flew high with the help of the Beatles, and a few hits, then collapsed in a mess of mismanagement and tragedy

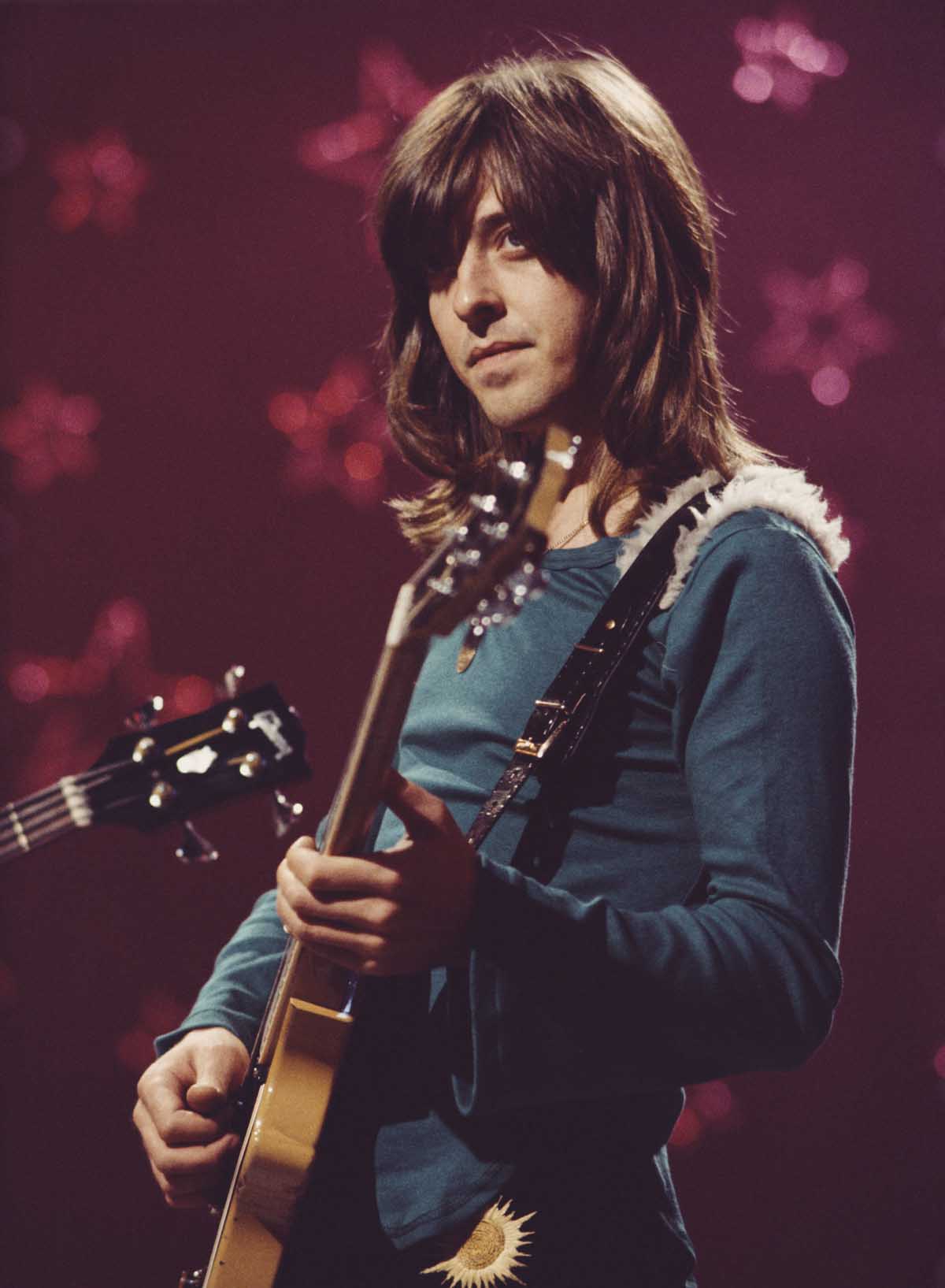

This interview with the late Joey Molland, guitarist and singer of Badfinger, was published in Guitar World in 2020.

“There are times when it all feels like a dream,” says guitarist Joey Molland, recalling the glory days a half century ago when Badfinger ruled the airwaves with a series of exquisitely crafted pop-rock hits like Come and Get It, No Matter What, Day After Day, and Baby Blue.

“Badfinger gave me the opportunity to do everything a musician could want. I got to make records. I heard my music on the radio, and I toured all over. I couldn’t believe the luck we were having. For a time, everything was great.”

The Liverpool-born guitarist joined the Welsh/English group, then called the Iveys (which also featured singer-guitarist Pete Ham, singer-bassist Tom Evans, and drummer Mike Gibbins), at a most fortuitous time.

It was late 1969, and the band was not only one of the first signings to the Beatles’ Apple Records, but they were about to experience their first blast of fame with the release of Magic Christian Music, the “pseudo-soundtrack” to the film Magic Christian that starred Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr.

Dropping the Iveys moniker for Badfinger (a reference to Bad Finger Boogie, the working title of the Beatles’ With a Little Help from My Friends), the band saw the album’s lead single, Come and Get It, a Paul McCartney-penned ear-candy gem that could have easily figured on Abbey Road, hit the Top 10 on both sides of the Atlantic in the spring of 1970.

“The Iveys had put out some records before Come and Get It that didn’t really take off,” Molland says. “People think that because the band was signed to Apple that they were just given a straight ride to success, but that wasn’t the case. It wasn’t until Come and Get It came out that the perception changed for Badfinger. Then people started to think, ‘Ahh, they can be a big success for Apple.’”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

After the success of Come and Get It, various members of the Beatles’ organization – including John Lennon and George Harrison – became more hands-on with Badfinger.

Lennon tapped Molland and Evans to play two cuts on his Imagine album, and Harrison produced half of the band’s 1971 disc, Straight Up (that same year, he also enlisted the group to take part in his historic Concert for Bangladesh at New York City’s Madison Square Garden).

For the first half of the '70s, Badfinger were flying high, racking up hit singles and albums while touring the world (Ham and Evans also saw their composition Without You, a Badfinger track from the band’s second album, No Dice, become a global No.1 when Harry Nilsson and producer Richard Perry gloriously re-imagined it on the singer’s 1971 album, Nilsson Schmilsson).

Yet despite their success, the group soon discovered they had little to show for it. American businessman Stan Polley, who had taken over their affairs from original manager, Bill Collins, defrauded the band out of millions, leaving them all but broke.

Desperate and in the throes of depression, Ham hanged himself in his garage in 1975. Eight years later, in an eerily similar and no less tragic manner, Evans also hanged himself following a dispute about unpaid royalties.

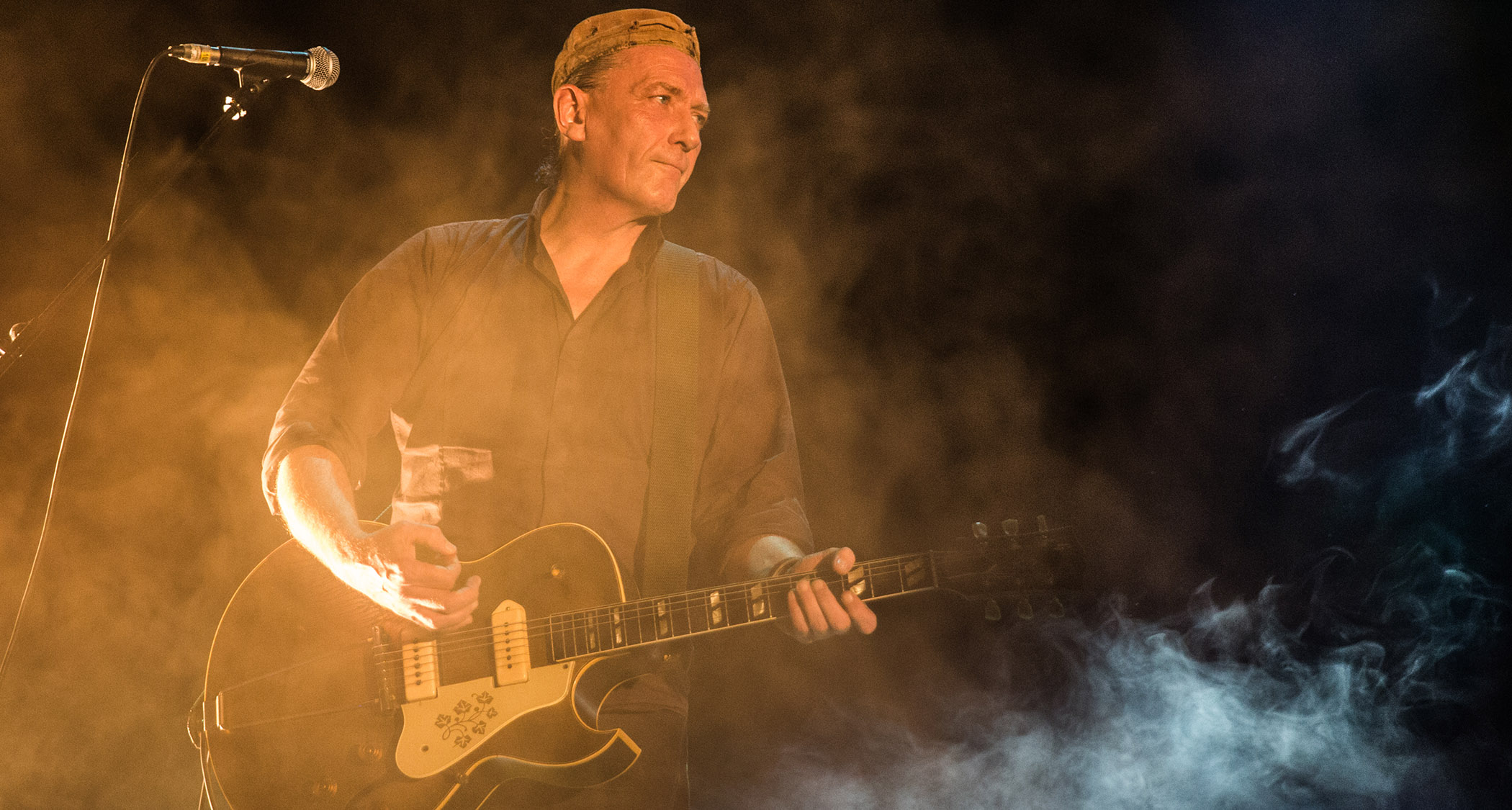

“People say things like ‘the saddest story in rock,’ and I guess they always will,” says Molland, who at 72 continues to tour with a band he calls Joey Molland’s Badfinger.

“I can’t get away from it, but I don’t really dwell on it. I try to focus on the good things that we did and all the great songs we recorded. I meet people all the time who know our music. Sure, I wish things didn’t turn out as they did.

“We had two people in the band take their own lives – that’s a tragedy on a human level. Who knows what drives people to do such a thing? But I can’t think about ‘what might have been.’ You go crazy if you live your life like that.”

What I knew of the Iveys was that they were a bit too pop for me at the time. I wanted to play guitar music with a harder bite to it

What kind of guitarist were you back in the '60s before you finally hooked up with Badfinger?

“I was pretty good. For me, getting into the guitar started when I heard Elvis Presley’s Blue Suede Shoes. From that moment on, I wanted to be a guitar player. I got really good at rhythm guitar quite quickly, and then I started learning how to play lead. I listened to Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly. I never thought I was great or anything – there were so many brilliant guitarists in England in the '60s. But I enjoyed it. Playing guitar was just fantastic.”

Did you know the band when they were the Iveys? What was the buzz on them?

“I didn’t really know any kind of buzz on them. Musicians didn’t really pay attention to them, I don’t think. I’d heard of them, but they didn’t mean that much. I wanted to play Chuck Berry music; I wanted to play beat music. What I knew of the Iveys was that they were a bit too pop for me at the time. I wanted to play guitar music with a harder bite to it.”

How did you come to audition with them?

“To be honest, I almost didn’t go to the audition. I’d seen them on TV doing a song called Maybe Tomorrow, and it wasn’t my cup of tea. I’ve got nothing against love songs, but I want them to come from more of a Tamla/Motown kind of thing – Martha and the Vandellas.

“But my friends in Liverpool insisted that I go and check it out. They thought the Iveys had something. So I went down and met the band. They had a house and we settled down to play together.

“They were really nice, and they wanted to play some beat songs. I sang for them a little bit, and they offered me the job. I think they were happy to find me. They had seen a few guys before me, but I was the only one who was writing some songs.”

Was there one Beatle who paid more attention to Badfinger – Paul McCartney or George Harrison?

“When I first joined the band, it didn’t seem as if anybody was paying attention to them. There was one guy, [Apple Records press officer] Derek Taylor, who seemed to take an interest, and [Beatles roadie] Mal Evans, who had gotten the band signed, he was involved. The Beatles weren’t really hanging around or anything. John Lennon didn’t really notice us. It wasn’t till Come and Get It happened that people took a real interest.”

Your first album with them, No Dice, featured No Matter What, which many consider to be the definitive Badfinger song. Did that sound like a hit when you were recording it?

“We knew it was a good song, and we enjoyed playing it. We went into the studio with Mal Evans and put together the arrangement. We didn’t record the basics at Abbey Road, but I went there to put on some slide guitar. I don’t know if anybody thought it was a hit. It took the label a little while to get the song on the radio, but once they did, the record did really well.”

Do you remember what kind of guitar and amp setup you used on that?

“I used the guitars I was playing at the time: a Firebird and an SG Standard. The Firebird was a guitar I was playing for years before I joined Badfinger. The SG was given to us by George Harrison. I think Pete really liked it. My amp was an AC30 that belonged to the band. I didn’t even have my own amp at the time. But I got a good sound out of the AC30. It was good for rock ‘n’ roll guitar.”

You worked with John Lennon on Imagine, and you played acoustic guitar on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass. What were the differences in working with the two?

“I did a lot more work with George than with John. George was very direct. He’d come over, sit with me or the other guys, and he’d play a song. I remember him doing that with Beware of Darkness; he had an acoustic, and he played it for us a few times so that we could get a feel for the tune.

“He was always very sweet but very direct. He knew exactly what he wanted as far as rhythm guitar: all straight up-and-down strokes. No jingle-jangle stuff. He made that very clear.

“But he was cool, and we became good friends. John was quite different. We were all quite freaked out about even seeing him. [Laughs] He was a complete genius as a singer, writer and just… well, he was John Lennon! It was very hard to get over that.

George Harrison was always very sweet but very direct. He knew exactly what he wanted as far as rhythm guitar: all straight up-and-down strokes. No jingle-jangle stuff

“He had an aura about him. I don’t remember if it was John or Phil Spector who suggested me and Tom for the album; I just recall John’s driver calling me and saying, ‘John’s doing some work in the studio. Can you come down and play some guitar?’ So the car came and we went to John’s place; we went into the studio, and there was John.

“It was about 10 o’clock at night and John looked like he just got out of bed. It was a friendly vibe. [Keyboardist] Nicky Hopkins was there, [drummer] Jim Keltner was there. Phil Spector was in the control room, and now that I remember it, so was George Harrison.”

What was Phil Spector like in the studio?

“I don’t really know – he never really talked to us! He sat in the studio and drank a lot of brandy. [Laughs] But what was funny was, you’d do a couple of takes of the tune, and then Phil would play you back a two-track mix – with echoes on it and everything. I guess he wanted you to know where he was going with it.”

George Harrison produced half of Straight Up. What was he like to work with as a producer?

“He was great as a producer. He was great at everything he did with us. He was very communicative. If he had an idea to change an arrangement, he would sit down and talk to you about it. He always had a good reason for doing something, but he wanted you to feel good about it. He was a very good producer in every way.”

Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick started that album as producer. Why were his tracks rejected?

“The American label people didn’t like them. We recorded 15 tracks or so with Geoff, and what happened was, the album got sent to America. The people in the States thought it sounded crude and rough. So they said to the people at Apple in the U.K., ‘Can you maybe redo the stuff?’ They didn’t like all the songs, and they hated the sound. That’s when the plan went to George Harrison producing us.”

We played with great bands. American bands played really well and could sing their asses off. The Rascals were amazing

George played slide guitar on Day After Day. I take it you didn’t mind letting a Beatle have a go at the guitar track.

“Oh, not at all. He even came in and asked us, ‘Is it OK if I do a little slide on your record?’ He didn’t just do it or demand it; he wanted to make sure it was what we wanted. I had a ’63 Strat, and that’s what he used. He sounded great. He was one of the best slide players ever. We were thrilled at what he did.”

Todd Rundgren produced half the album, including Baby Blue. What was he like?

“He didn’t really think about what he was going to say before he said it – he just said it. He was very rude, actually, and we didn’t like him. We were quite happy when it was over. He went away and took the tapes; we never did overdubs or anything. He took the tracks that George had done and mixed them. We just heard the record when it came out.”

What was touring like in the U.S.?

“It was great, man! It was fantastic! We did 50 or 60 dates on our first tour, and then a year later we did another tour. People seemed to really like us over there, and we went over like mad. We loved learning about America. The hippies were all over the place – it was cool. We played with great bands. American bands played really well and could sing their asses off. The Rascals were amazing.”

What are your feelings on the band’s original recording of Without You versus the version Harry Nilsson had a giant smash with?

“We were astounded when we heard Harry’s version. It was great that it was so successful – it was Song of the Year. Our manager, Bill Collins, wanted us to do a big version of the song. Maybe he heard what Harry eventually did, but we just weren’t that kind of band.

“We didn’t do big versions of things; we wanted to be a rock band. We had guitars in our songs! So we did our version of it, and that seemed fine. But yeah, the Nilsson track became huge. Tommy and Pete won the Ivor Novello Award for it. We were all quite pleased for them.”

We didn’t have any money. Think about that: We were selling millions of records and were on the radio all day, all over the world. We were broke! We were driving secondhand cars

Was calling the band’s 1973 album Ass met with resistance?

“[Laughs] I’m sure. I didn’t hear a lot about it, really. It kind of made sense with the other titles – No Dice, Straight Up. We had a bit of a lowbrow sense of humor. I wasn’t involved in those things. I never went down to Apple to talk about titles. I thought that was a good album. We were changing our sound a bit more at this time. We were jamming more. I think we would have gone a long way with that.”

Were there tensions within the band at this point? Did you have any inkling that Pete Ham would commit suicide?

“There were some tensions, but not necessarily from Pete. The problems really started when this guy, Stan Polley, got involved. Pete had a lot of faith in him, and I don’t know why because the guy was a crook. That’s what I call him – ‘the crook.’ It was just blatant. Pete and Tommy had been warned when the band left Apple and signed to Warners to get rid of him.

“Pete actually left the band at one time. He came back after a few weeks and wanted back in. I asked him what we were going to do about Stan, and he didn’t want to do anything. I said, ‘Well, what’s the point in this?’

“We didn’t have any money. Think about that: We were selling millions of records and were on the radio all day, all over the world. We were broke! We were driving secondhand cars. We got a salary of $300 a week. And then I quit – I just couldn’t take what was going on anymore.

“Pete called Stan because he needed some money to buy something for his girlfriend, and he was told that he had no money left. Nothing. It was horrible. Did I have any idea that he would kill himself? No, not at all.”

After Pete killed himself, the band broke up for a time, but some years later you and Tom got together again.

“Yeah, I moved to Los Angeles and started knocking around, doing what I could. I had no money. I met some guys who wanted to put a band together, and I liked them, so we started something up.

“We needed a bass player, so I called Tommy and asked him what he was up to. He was working in a hardware store or something. So he came over and played bass, and we made some demos. When he and I sang together, it sounded like Badfinger.”

But you didn’t want to call the band Badfinger.

“No, we didn’t. Elektra/Asylum called it Badfinger. It wasn’t our idea. We were uncomfortable with the whole thing, but we went along with it.”

It’s been reported that it was because of an argument about royalties between you, Tom, Mike Gibbins, and Bill Collins, your former manager, that Tom also hanged himself.

“It was very complicated. I had an argument the night before he died; he was talking about getting that money from the cohorts. I’d been to England and tried to get the money.

I feel as if things could’ve turned out differently. If we had different management, we could have gone on

“We had to all sit down at a table and agree how it was going to be divided, and then we had to get lawyers involved. Pete’s heirs had to be involved, too. All of us had to agree to it. Tommy wanted it done a certain way, but I wanted it to be done the way we had agreed originally. So did the others.

“Tommy had his reasons for it, but they weren’t our reasons. He told me that night he was going to kill himself. It was surreal. It had nothing to do with Pete dying, as some have suggested. It was eight years later. You know, it’s a shame.

“I feel as if things could’ve turned out differently. If we had different management, we could have gone on. Getting involved with the crook was the worst thing we ever did. We could always write songs; we could always play. We just had bad business, and it finished us.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“I knew the spirit of the Alice Cooper group was back – what we were making was very much an album that could’ve been in the '70s”: Original Alice Cooper lineup reunites after more than 50 years – and announces brand-new album

“The rest of the world didn't know that the world's greatest guitarist was playing a weekend gig at this place in Chelmsford”: The Aristocrats' Bryan Beller recalls the moment he met Guthrie Govan and formed a new kind of supergroup

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)