From the Archive: The Decemberists’ Colin Meloy talks Acoustic Guitar and Songwriting

The following was originally published in the February 2007 issues of Guitar World Acoustic.

The prospect of talking about his guitar playing has Colin Meloy, frontman of the Decemberists, palpably excited. “No one ever asks me stuff like this,” he says from his home in Portland, Oregon. “It’s a refreshing change.”

That no one asks Meloy about his six-string work is no reflection on his skill or accomplishments. It’s just that, since their formation in Portland, in 2001, the Decemberists have attracted far more attention for other things, such as their tendency to costume themselves in pirate outfits or Civil War military dress at gigs and photo sessions.

Meloy also gets lots of press for the anachronistic, often bombastic language and imagery that he works into his song lyrics. Take, for example, the opening line to “The Perfect Crime #2” from the band’s fifth album, The Crane Wife (Capitol): “Sing, muse, of the passion of the pistol.” Except for the part about the pistol, it’s a passage right out of the ancient Greek poetry of Homer and Hesiod.

That Meloy, a native of Montana, is an unusually bookish rocker is clear from the name of his band. The original Decemberists were a group of Russian army officers sent into Siberian exile in 1825, after their unsuccessful attempts to convince Czar Nicholas I to establish a national constitution.

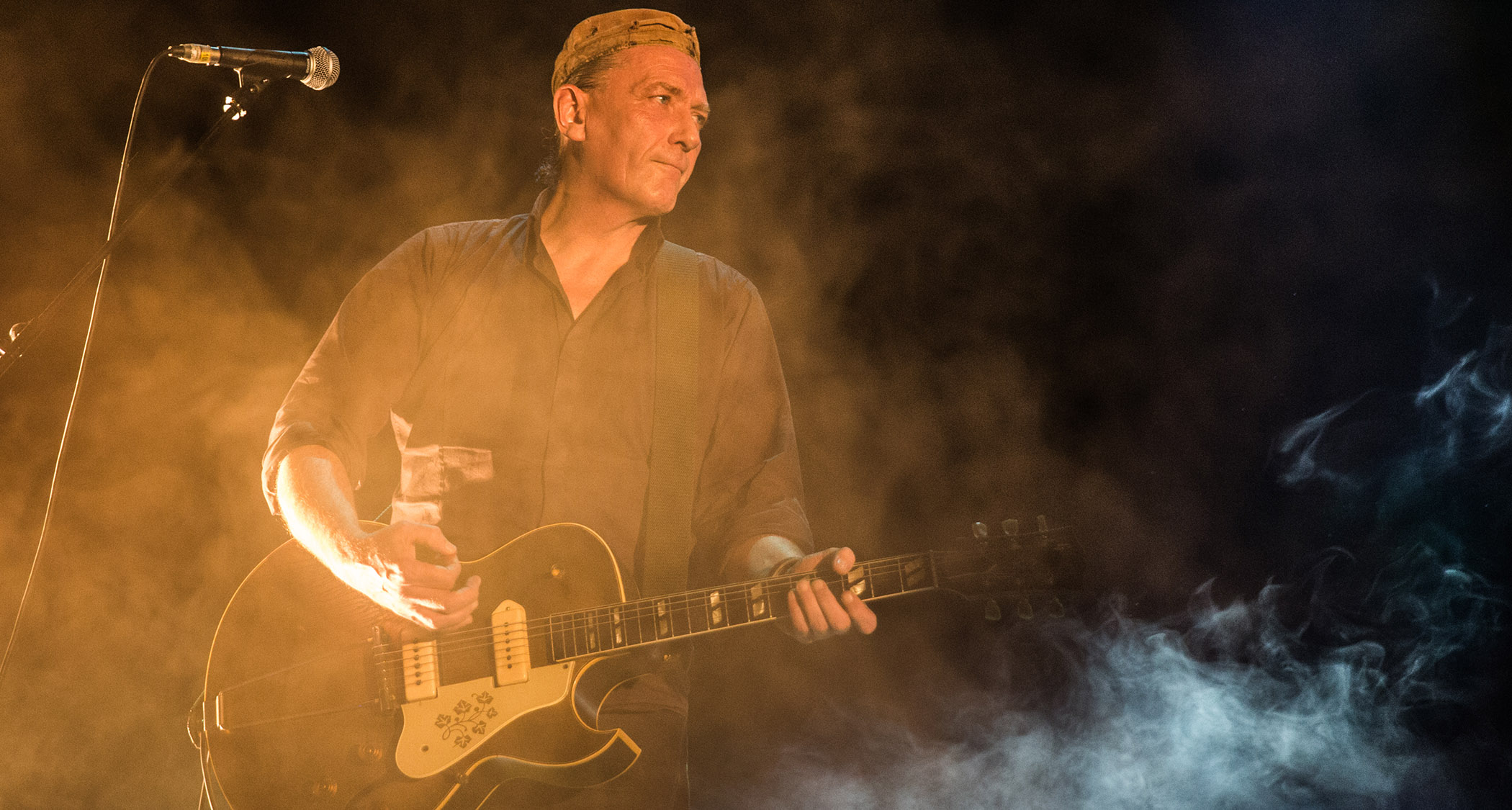

But for all his erudition, Meloy is a songwriter, not a poet or historian, and the power of his songs owes as much to the sound of his band as to his unusual lyrics. Ambitious, idiosyncratic and strangely endearing, the Decemberists’ music is imbued with the flavors of both “olde English” folk and 1980’s-vintage British rock of the sort played by the Smiths and the Waterboys.

And the centerpiece of most of it is Meloy’s acoustic playing - which is why a guitar-focused interview is long overdue.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Tell me about your development as a musician. Was guitar your first instrument?

Initially, my parents got me a piano teacher, but that never really took hold. I had a hard time being interested in things like practicing and remembering to bring my theory books to the lessons. After I started getting into rock bands in sixth grade, my parents thought it might be a good idea for me to start taking guitar lessons. It just so happened that I was taking guitar lessons at the same time that I bought the Jesus and Mary Chain’s Psychocandy, and if you’re familiar with that record, you’ll know that there’s rarely more than three chords in any one songs. I suddenly realized that with just the barre chords I already knew, I could play any song on that record, which was a really eye-opening experience for me.

So was that the end of the lessons?

No, I kept taking lessons all the way through high school. But once I’d learned a bit more about chording, I started to lose interest in things like scales and focus more on putting chords together in songs. I never learned to read music very well; for the most part I learned by ear and playing along with records. It got to the point where my lessons would consist of me bringing R.E.M. and Smiths records to my teacher, who would then play through them with me, explaining how the chords related to each other.

How did you originally become interested in bands like R.E.M. and the Smiths? They weren’t exactly mainstream listening in mid-Eighties America, and certainly not in Montana, where you grew up.

My uncle Paul, my mother’s youngest brother, was in college in the mid-Eighties while I was in fifth and sixth grade, and he was discovering all that alternative music. He started making mix tapes and sending them to me. Great stuff. That’s where my music obsessiveness came from.

Another artist who did excellent work during that era is Robyn Hitchcock, and is sounds like he’s influenced you a great deal.

Definitely. His album Globe of Frogs was one of the things my uncle sent me from college, and I became a diehard fan after that. I love the way he combines open and fretted strings in his playing, like that E chord he likes to play up the neck [see chord box]. “The Crane Wife 2” is probably the most Hitchcock-y thing I’ve done, with lots of hammer-ons from open strings.

Your music often reflects the direct influence of very old song forms: hymns, sea chanteys, murder ballads. How did you interest in these traditional styles come about?

Probably my first realization that folk music could be really powerful came when I discovered the Pogues in junior high school. From there it was just a matter of following the lineage - from [Pogues singer] Shane MacGowan to Terry Woods, who was a member of both the Pogues and Steeley Span, to [early Seventies British folk legend] Anne Briggs, who recorded with Terry Woods, and so on. I’d heard about Fairport Convention for years, but it was only about three years ago that I actually listened to them. I bought their album Liege and Lief, and it was one of those records that I couldn’t believe I hadn’t heard before. That led to a lot more exploration of the Sixties and Seventies British folk revival, and a lot of that music blew me away.

Have you always been a predominantly acoustic player?

Pretty much. I never got a grip on playing electric. I learned my strumming patterns on acoustic, and as a consequence I hit really hard and tend to fret really hard, too, which is not so good on electric guitar - I push the strings down with such force that the notes can get a little pitchy.

We’ve talked exclusively about your music and guitar playing here, but I do want to ask you something about your lyrics. The characters in your songs - every one of them, it seems - meets some terrible end. You also use antique-sounding language to tell your stories. Have you always written songs this way? What prompted you to adopt such a style?

I recognized pretty early on that what set someone like Robyn Hitchcock apart was his unique approach to writing lyrics. I was attracted to the absurdism in his songwriting. And when I started writing songs in high school, I would toy around with a similar sense of absurdity in the language - which sounded really ridiculous at first. As for the subject matter, I guess that in my imagination I’ve always leaned toward dark, horrific things. It’s just what I find fascinating. Yeah, my characters are destined for a bad end. We all are, eventually.

More about Meloy and The Decemberists at http://www.decemberists.com

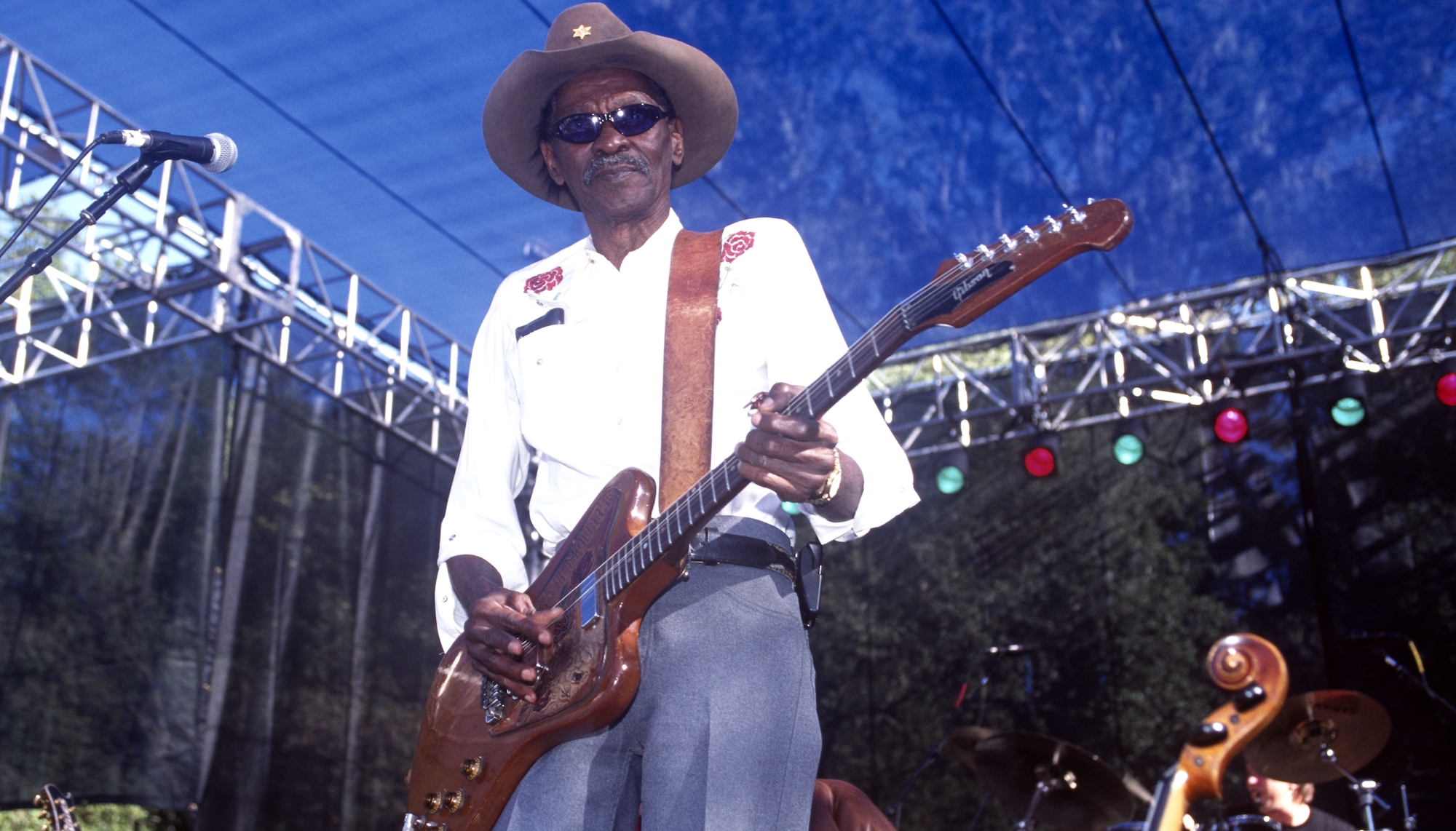

“Muddy Waters and BB King, I knew ’em before they passed away, and they told me, ‘Man, if you outlive me, just try to keep the blues alive’”: Buddy Guy has officially retired from touring – but he’s back on the big screen in Michael B. Jordan’s Sinners

“I can’t believe how complicated the parts she’s playing are. You just never know how those are coming to be in the studio”: FINNEAS reveals his surprise guitar hero whose playing left him scratching his head