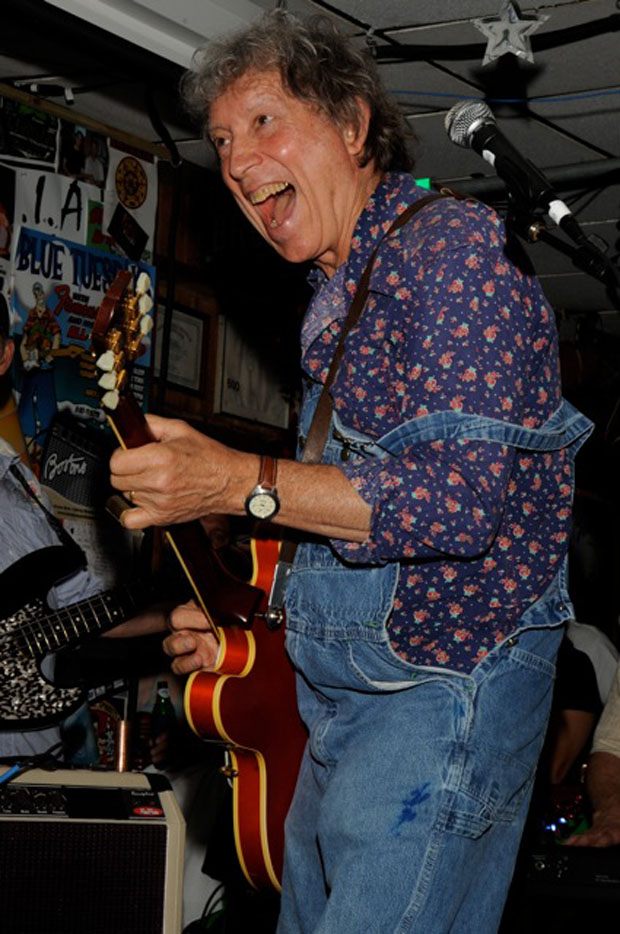

Interview: Elvin Bishop and his “Red Dog” Gibson ES-345 — Together Almost 50 Years

Before Eric Clapton was old enough to shave, Elvin Bishop was hanging out in Chicago with the first generation of electric bluesmen.

A native of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Bishop brokered a National Merit Scholarship into an education that majored in 12-bar theory, generally off the University of Chicago campus he was enrolled at. When he wasn’t jamming with Muddy Walters or Junior Wells, he was dutifully going on lunch and liquor runs for Hound Dog Taylor.

In 1963, he met another young, white blues fan, Paul Butterfield, and rock history was made. On his own since 1968, he established a successful and prolific career as a recording and touring artist that continues to this day. And he still gets royalty checks from “Fooled Around and Fell in Love,” which peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard singles charts and lives on in commercials, films and karaoke bars around the globe.

Also a graduate of the 12-step program, his hard-partying days are long behind him and he picks and chooses his gigs, which of late have included several voyages on blues cruises. One thing that has not changed for nearly 50 years, however, is his constant companion, a Gibson ES-345 — 1959 edition preferred — a cherry red axe he affectionately calls “Red Dog.”

Having released his latest recording, Elvin Bishop’s Raisin’ Hell Revue, earlier this year, Guitar World found Bishop enjoying the workweek at home. Come the weekend, as per usual, he’ll fly the friendly skies to another gig. Later this month, he’s scheduled for another blues cruise off the Pacific coast (October 23 to 30) with guest vocalist Mickey Thomas, who sang lead on “Fooled Around and Fell in Love” before he joined Jefferson Starship.

GUITAR WORLD: It’s been a busy year for you. What are you doing right now?

We’re kind of in-between. We were real, real busy this summer, kind of ridiculous, you know. We went back and forth to Europe three times, and all over this country. And then this month, we’ve had a little time off. I’m sitting here in my garden right now.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What’s a typical year like for you?

I don’t road dog it like I used to, 200 or 300 nights a year. I don’t know, 50, 75 [shows]. Usually we just fly out somewhere on the weekend.

Still in demand after all these years?

Evidently. I’m in a good position because I’m sort of able to take the gigs that look interesting, and pay well, you know. After all these years, the romance of the travel has worn off quite a bit. And boy, flying ain’t as much fun as it used to be, you know? But the music is still great. That’s the most important thing.

When you get to pick and choose, what kind of gigs do you pick?

They’re basically all good once you get in front of the people. I like ones where you can really see the people, and get with them, and do the whole thing together. What I don’t particularly like is when you’re on a really high stage, and the lights are shining in your eyes, and you can’t even see the people. That to me, that’s not the fun part.

Do you enjoy the blues cruises? Your latest record, a live show, was recorded on a blues cruise.

That’s right, one of these cruise boats that this guy, Roger Naber from Kansas City, puts together. I guess he’s been doing it for a quite a few years. We do it every year. We’re doing it again this coming month.

Doesn’t a cruise get a little claustrophobic? Do you have to mingle much with the guests? Can you get any privacy?

It doesn’t really bother me. I resisted the notion for quite a while because who wants to be stuck on a boat with two or three thousand maniacs? It’s not really like that. They give you as much space as you want and as much contact as you want. They’re really nice people, very into the music.

I guess you never imagined, as a teenager playing blues in Chicago more than 50 years ago, that you would be jamming on a fancy blues cruise.

Oh, no. In the first place they’re mostly white people [on the cruise], and when I started out there weren’t any white people in the blues.

Except on stage, of course. People like yourself.

Not even that, just maybe, me and you can count on the finger of one or two hands the number of white people who were into the blues in any form or fashion.

I’ve seen the phrase “white blues” attached to your name often. Does that phrase bother you, and do white blues exist?

I don’t hear that as much as you seem to. I don’t know. To me, this generation of kids has come up with one phrase that makes sense, “It is what it is.” Outside of the guys who grew up picking cotton by hand and plowing with mules and stuff, totally pure blues is a very limited thing. Just about everybody else has been exposed to all kinds of influences, and what you get is their personal combination of those influences. You look at Ray Charles or Jerry Lee Lewis, or Chuck Berry, or any of those people, what you get is some of what they are. There’s gospel in there, there’s country in there, there’s pop. What you’re looking for is what that individual has to bring to the table.

You have your share of influences, but you got to learn directly from some of those original blues masters at a very early age. What was that like?

I came [to Chicago] from Oklahoma and school was a cover for me. I came from a long line of farmers and there had never been anything else in the family. I got a scholarship and had a chance to go anywhere I wanted to, and I went to Chicago. I had fallen in love with the blues before that, but it was just the sound of it. I didn’t know the lifestyle that went with it, or what the people were like or, in a lot of spots, what the words meant. Because Ebonics is like a slightly different language from English. In Chicago, I got to meet these guys, and go stay in their houses and see how they lived, and how the music connected up with the culture. That was the beauty of it all.

Were you accepted in that culture?

I’ve always been lucky in my career in that I’ve got to meet all my heroes and play with them just about. Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Albert Collins, Otis Rush, Magic Sam, all those guys. Junior Walker. Those guys were super nice to me.

I guess it was a good time to be quiet and listen.

That is absolutely right. I didn’t come on strong. It was a little bit different of a world then. I came from a lifestyle where older people were little more respected than they are now. I’d meet those guys and go over their house. And if, say, Hound Dog Taylor wanted a sandwich or a half-pint, I’d go to the corner and get it for them.

One gentleman in particular played a big role in your education, correct?

Little Smokey Smothers, A wonderful guy. He was never lucky enough to make any records that made any noise but he was a great player and pretty much universally liked and admired by all the blues musicians in Chicago. Smokey took me under his wing, showed me the ropes and helped me out.

Who influenced you most purely as a musician?

One of my heroes was a guy named Earl Hooker. You can ask any Chicago blues guy, he was known as the greatest guitar player of the time. He played melodies like a voice. He would play like a Ray Charles tune, you could close your eyes and see Ray Charles singing, he was so good.

Fast-forward a bit. You blazed trails with the Butterfield Blues Band, you had a big hit in the 1970s with “Fooled Around and Fell in Love.” There’s a line on your own website that refers to “rediscovering the blues” in the 1980s, but it seems to me they are always a big part of what you did.

That’s something that some writer chose to say. Blues were just a fact with me all along, like you say.

What else caught your ear and comes out in your music?

I’m from Tulsa, Oklahoma. You get country there just by breathing the air. Gospel, I love Gospel. I had somewhat of an attraction to jazz but my mind didn’t move fast enough for that.

A lot of those blend nicely in “Fooled Around and Fell in Love,” which has that great hook. Was there a conscious effort on your part to record something that would hit on the pop charts?

It happened by accident, to be honest with you. Here’s a bit of trivia for you: [Our producer was] the guy who got B.B. King and me our only hits, the same guy who produced “The Thrill is Gone.” He also produced the Eagles, so he obviously was trying to make it a hit, trying the best he can, that’s what producers do.

That was Bill Szymczyk, right? I’ll have to spellcheck that name.

Yeah, big waste of consonants. We were making an LP and we had 10 or 11 songs. He said we need one more piece of material. “What else you got laying around?” So I said “What about this?" I’d tried to get three or four good singers to do it and nobody was interested. So we cut a track of “Fooled Around and Fell in Love.” I tried to sing it, and then I said, “Well, that’s not going to butter the biscuit.” So I asked Mickey if he would be willing to try it and he just knocked it dead. And Szymczyk just did a great job of mixing it. Got a great sound on the instruments.

When you played it back, did you realize you had a hit on your hands?

No, I had no idea. I don’t have a feel for that sort of a thing. Everything that has happened to me in the music business over the years has been a complete surprise to me. I just try I just try to play to my taste and hope somebody likes it.

It seems that when you like something, you stick with it, particularly guitars.

I’ve kept the same guitar for basically my whole career, since the early ’60s.

Which guitar is that, for the record?

A 1959 Gibson ES 345. If you listen to the tune “Red Dog Speaks” on my latest record, that will tell you the story.

How did you and the Red Dog meet?

Well I got my first one from a guy named Louis Myers. He was great blues guitar player. He played with Junior Wells, Little Walter, and he played with a band called the Aces that was really influential in Chicago blues. Made a lot of hit records. He came by my gig one time, I’d say about ’63 or so, and I had a Fender Telecaster and I used to break the strings on it all the time. There was something wrong with the neck, and down around the bridge there’s something sharp there, and it kept breaking strings. And I said “Oh, man, this is a drag. I’m breaking too many strings on this guitar.” He said “There’s nothing wrong with that guitar, you’re just square as a pool table and twice as green. You don’t know what you’re doing, that why you break strings.”

And he had his guitar with him, which was a Gibson 345, and I said, “Man, if I had a guitar like that, I bet I wouldn’t break no strings.” He let me try it and I said “This thing feels great.” He said “Tell you what. I’ll trade you guitars, and I won’t break a strong on this one and you’ll keep breaking strings.” We traded — I guess he was a little high or he wouldn’t have done it — then he comes back about a week later and says, “Man, every time I pick this thing up, a string pops. We got to trade back.” By that time, I had gotten used to the Gibson. I don’t know, I shoulda traded back with him, but I just loved that guitar so much that I’ve had it ever since.

You mean you use that exact same guitar?

No, every five years or so, either the thieves or the airlines, something would happen to it and I’d go buy another one. … I still have a 1959 but I don’t take it on the road any more. It’s just too precious. To find a 1959 is almost impossible. … I use a newer 345 on the road.

Do you ever use anything else?

No, not really, I just try to get better on the one I got. It just suits me.

Does it need any special care and feeding?

I use my own kind of strings. Guess you’d say light on the top strings and heavy on the bottom, because I’ve got kind of a little too heavy of a touch and I need the stout bottom strings. If you’ve got your pencil, .10, .13, .17, .32, .42, .52.

You’re a distinctive singer as well, but it always seems that if you don’t have one other good lead singer in your band, you have several. Why is that?

I don’t know, I like to hear good singing, I guess, and I like my show to be a rich experience for everybody.You have been quoted as saying your limitations as a singer have improved your songwriting. Can you explain?If you don’t have that kind of naturally beautiful voice, where everything comes out sounding great, a person with a raggedy voice like mine has to have a strong story and deliver it well … to capture people’s imagination.

You also present a character onstage of sorts, of someone who, let’s say, looks like someone you would have fun partying with. I’ve never gone out of my way to project any sort of certain image. It’s just I guess how certain people perceive me.But you have curbed your wild ways a bit since the good old days.Yeah, I got my money’s worth out of it. I’ve been there and done that, that’s for sure. … [now I’m] 23 years in AA.And 35 years after it was a hit, you’ll be doing “Fooled Around and Fell in Love” with Mickey Thomas on another cruise.Yeah, I just spoke to him on the phone last week, real nice guy. It’s gonna be a lot of fun.I just saw a good clip of you guys together onstage in 2008.Yeah, it had been a very long time. We hadn’t had a lot of contact over the years but what we did was cordial. We played again one other time since then, I think, in 2010.So you never had a problem with him singing that song on his own, or when he used to do it with Jefferson Starship?No, why not? Keeps it out there, I guess, which never hurts. Do you mind me asking, do you still get checks from that record?Yeah. That tune has been in about 20 movies, I’d say. Rod Stewart recorded it last year, so that was quite a little financial bump there.

“I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. My head was huge!” “Clapton is God” graffiti made him a guitar legend when he was barely 20 – he says he was far from uncomfortable with the adulation at the time

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul