How Jimmy Page was reunited with his beloved 1960 Les Paul Custom – nearly 50 years after it was stolen

The Led Zeppelin legend's triple-humbucker Black Beauty was stolen at a Minneapolis Airport in 1970. Here's the incredible story of how it made its way back to its rightful owner

In April of 1970, fresh off the triumph of their first two albums, Led Zeppelin were touring North America for an astounding fifth time in two years. The quartet was determined to become the biggest band in the world, and there was every indication that they were well on their way.

Their live shows had become the stuff of legend, breaking attendance records, and on this particular one-month jaunt, they would gross a total of more than $1,200,000 – roughly $8 million in today’s money. But their experience on tour was not without its glitches. And a major one was the U.S. South and its still ultra-conservative mores.

“It was my dream to play Memphis,” Jimmy Page told Guitar World back in 2008. “I grew up loving the music that came out of [there] and Nashville. But it turned out to be really depressing. We arrived in Memphis and were given the keys to the city [because] the mayor was astonished at how quickly ‘this Led Zeppelin fellow’ had sold out the local arena. It occurred to him, whoever this ‘guy’ was, he must be important.

“We got the keys in the afternoon, but I guess they didn’t like the looks of us. Shortly after, we were threatened and had to get the hell out of town as soon as we were done with the show. I was really mad because there were all these places I wanted to go – Sun Studios, where Elvis Presley had recorded, and so on. They didn’t like the long hair at all, man. It was seriously redneck back then.”

“Then we played Nashville the following night. We were in the dressing room, getting ready to go out and do an encore, and this guy walked in and he said to us – ‘If you guys go back out there, I’m gonna bust your heads.’ And he wasn’t kidding. We were part of a subculture [they] didn’t want the kids to know about – hippies with long hair.”

But Page and the band’s unnerving adventures in the South were a mere bump in the road compared to what happened a couple of weeks later, far to the north. Toward the end of the group’s month-long American trek, they traveled from Minneapolis to Montreal, Canada.

Crossing the border was often a hassle for rock and roll groups, as Canadian customs officials often spent extra time going through their equipment, searching for contraband. To avoid the bother, Led Zeppelin often chose venues close to the border so their Canadian fans could see them in the States. But this time they decided to bite the bullet and fly to Montreal.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Everything went surprisingly well until Page noticed that something was missing: his prized black 1960 Gibson Les Paul Custom – a deeply personal favorite he had used since his early days as a top British session musician. “We went over the border, but my ‘Black Beauty’ didn’t turn up at the other end,” Page recalls in his new book, Jimmy Page: The Anthology.

“There were so many points in the journey where it could’ve gone missing – at the original airport, at customs, at the airport in Canada – but all I knew was that it wasn’t there, and in those days, nobody could trace it. We played the concert in Montreal and there was still no news on the electric guitar. It had evaporated.”

After he was certain it had been stolen, Page did the only thing he could think of, which was to take out a “missing guitar” advertisement in Rolling Stone that ran in every issue for the next year.

Unfortunately, the only response he received was silence, and thus began one of music history’s biggest mystery stories – a perplexing whodunnit that most thought would never be solved.

In the Beginning

To appreciate the guitar’s significance to Page, we have to travel back to England in the late Fifties. During that time, Page played in several exciting London rock and blues bands, like Red E. Lewis and the Redcaps and Neil Christian and the Crusaders, while experimenting with different guitars and sounds.

After cutting his teeth on two serviceable instruments, a 1958 Hofner President and a Czechoslovakian-made 1959 Grazioso Futurama, Page moved on to a pro-level sunburst Fender Stratocaster.

The Strat was a fine guitar, but the young Page wasn’t quite ready to settle down with one instrument. Enamored with the fingerpicking style of country superstar Chet Atkins and rockabilly guitarist Cliff Gallup’s use of the Bigsby tremolo, Page acquired a 1960 Gretsch Chet Atkins 6120 model featuring a beautiful and highly figured, flamed maple top and a Bigsby.

“I was keen to be able to play [like Atkins],” Page said. “And Paul Bigsby was an extraordinary innovator, and there’s a totally different mechanism on his tremolo arm compared to the one on a Stratocaster. The combination… was enough for me to go up to London, play [a Gretsch 6120] in the shop and trade in the Fender Stratocaster.”

It seemed like Page had found his ideal guitar, but several months later he was walking down Charing Cross Road in London and decided to stop by Lew Davis, a small music shop that doubled as an informal gathering spot for local musicians. There he saw something that literally stopped him in his tracks, made his palms sweat and his heart beat a little faster.

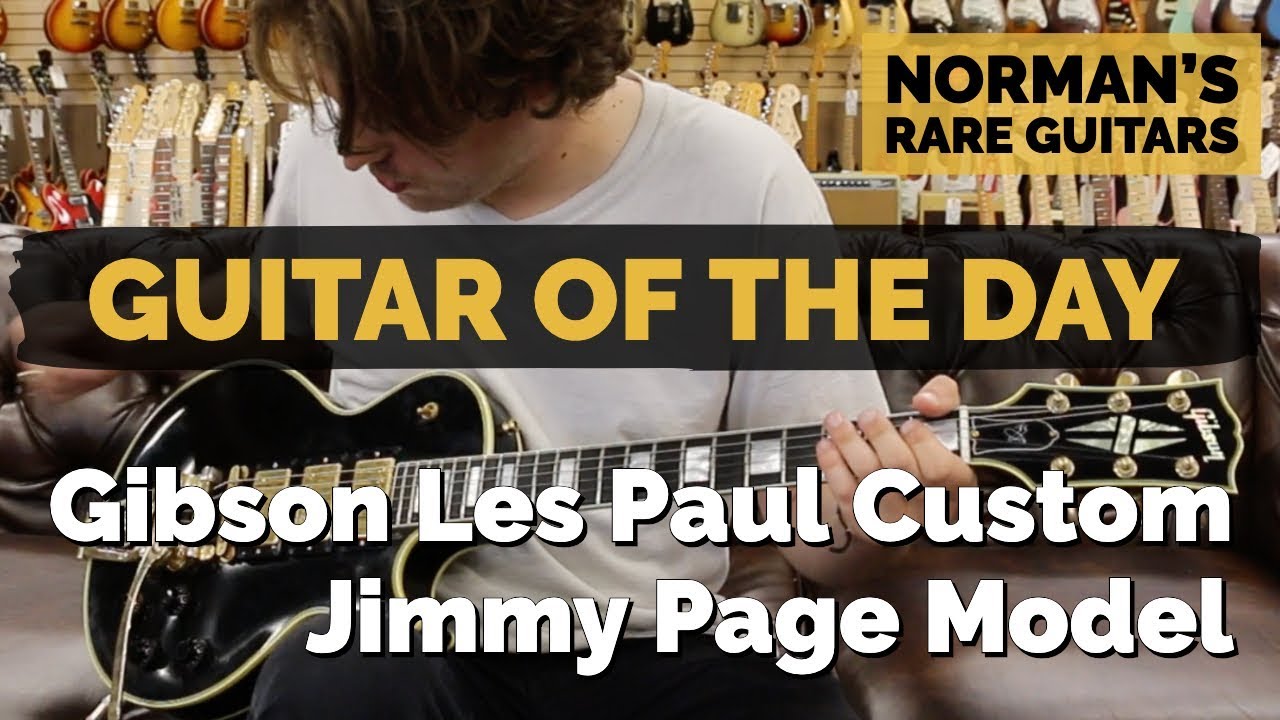

“There was this guitar hanging on the wall looking so bloody sexy,” Page said of the new (1960) tuxedo-black, three-pickup Les Paul Custom with flashy gold hardware and a Bigsby tremolo. “It was saying, ‘Come on then. Come on, stop looking and ask them if you can play me.’ I played it unplugged for quite a while. Then when I plugged it in it was like a dream, and I knew this was it. It sounded extraordinary. I knew it was coming home with me.” .

There was this guitar hanging on the wall looking so bloody sexy. When I plugged it in it was like a dream, and I knew this was it. It sounded extraordinary

Jimmy Page

Page wasn’t sure how he was going to pay for the deluxe instrument, but something came up that eliminated those money worries enough so that he could have his dream guitar.

While playing at the Marquee, a small club in the heart of the music industry in London’s West End, he was headhunted to work as a session guitarist for the Columbia Graphophone Company and Decca Records.

His first session for Decca was the recording Diamonds, by Jet Harris and Tony Meehan, which went to Number One on the U.K. singles chart in early 1963, and soon Page became one the most in-demand studio guitarists in England

Legendary producer Shel Talmy was particularly impressed by Page’s command of rock and blues, and he asked him to play on the Kinks’ 1964 debut album and the Who’s landmark first single, I Can’t Explain. But that was just the tip of the iceberg.

Jimmy and his Les Paul Custom can be heard on literally hundreds of tracks from that era, including Shirley Bassey’s dramatic Goldfinger and Them’s intense garage rock version of the blues classic, Baby, Please Don’t Go. So busy was he that it’s estimated that his guitar can be heard on 60 percent of the tracks recorded in Britain in the early Sixties.

”I’d used it to play those Eddie Cochran numbers and it was a real good backup guitar to have. It really sounded terrific. It was a leap of faith to take the guitar on the road… and look what happened”

Jimmy Page

With its three humbucking pickups, the black Les Paul afforded Page wide tonal flexibility, making the instrument perfect for just about anything he was called on to play.

It was with this guitar that Page built his reputation and became one of the most respected players in England. One can only imagine the professional and emotional value he placed on the instrument.

Perhaps one indication of the guitar’s significance to him is that when he eventually moved on to playing in the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin, he almost never took it on the road with him, unwilling to take any risks with the instrument. In fact, the fateful 1970 North American tour was the first time he dared travel with it for an extensive period of time.

“I was using my sunburst Les Paul Standard I bought from Joe Walsh in 1969,” Page told Guitar World, but I sort of plucked up the courage to take the Custom guitar on tour with us, because when we did the Royal Albert Hall show [captured in its entirety on 2003’s Led Zeppelin DVD], I’d used it to play those Eddie Cochran numbers and it was a real good backup guitar to have. It really sounded terrific. It was a leap of faith to take the guitar on the road… and look what happened.”

The heist

What did happen? That was the million-dollar question. For the next 20 years Page and his associates searched in vain for any sign of the instrument, with no luck.

Then, one day in the early Nineties, there was an indication that the real guitar may have finally surfaced. Nate Westgor, the owner of Willie’s American Guitars, a well-regarded St. Paul, Minnesota, vintage guitar shop, had a curious encounter.

“A guy I had never seen before walked in the store with a 1960 Les Paul Custom and said, ‘I have Jimmy Page’s stolen guitar,’” remembers Westgor. “To be honest, I didn’t believe him. There was no internet back then, so there was no easy way to check out his claim.

“And all those ads Jimmy ran in Rolling Stone years ago weren’t readily available, so we didn’t have the serial number or frame of reference. I was skeptical, but it was a nice guitar, so I offered to consign it while I promised to dig around. When I asked him how he got the guitar, his story was just weird enough to make me think there might be something to it.”

According to the customer, whose name has been lost over time, he obtained the Les Paul from the widow of a Minneapolis airport employee who’d stolen the guitar in 1970 when Zeppelin came through town, and then kept it under his bed until he died. “He bought the guitar for $5,000 from the woman, and he just wanted his money back and to get [it] back to Jimmy,” Westgor says.

The store owner’s first call was to one of Page’s confidants, producer and guitar collector Perry Margouleff. Margouleff was on the East Coast at the time and asked Peter Alenov, a respected St. Paul-based guitar dealer who sold instruments to the likes of Keith Richards and Eric Clapton, if he would check out the guitar on his behalf.

This is where the story should have ended happily for Jimmy. But it didn’t, as his beloved guitar again went missing – for another two decades.

A guy I had never seen before walked in the store with a 1960 Les Paul Custom and said, ‘I have Jimmy Page’s stolen guitar. I didn’t believe him. There was no internet back then, so there was no easy way to check out his claim

Nate Westgor

The Toggle Switcheroo

Few photos of Page with his Les Paul Custom existed, so only a handful of people knew that it had been modified.

A typical three-pickup Custom comes with a single three-way toggle switch that allows players to activate their pickups in this fashion – neck pickup only; neck and middle pickup; bridge pickup only. Jimmy, however, added two additional toggle switches so he could activate any combination of pickups, change their phase relation or turn them off completely .

When Perry asked Alenov to inspect the instrument, he didn’t tell him about the extra switches. “Pete really knew his stuff and I trusted him implicitly,” Margouleff told Guitar World, “but I didn’t describe the instrument in any detail. I didn’t want to color his observations.”

If the guitar had been refinished in the Seventies or something, that repair work would have had time to sink in, and Pete was a very sharp guitar guy, he would have spotted it

Perry Margouleff

“He called me up and he said, ‘I’m looking at this guitar. It’s a black 1960 Les Paul Custom… it’s totally stock. It’s got a Bigsby, foil cap knobs…’ and so on… I said, ‘Thanks a lot. You can go home now, we’re done.’ I didn’t need to hear anything else because I knew the guitar was supposed to have three toggle switches on it.

“If the guitar had been refinished in the Seventies or something, that repair work would have had time to sink in, and Pete was a very sharp guitar guy, he would have spotted it. He would have said, ‘Hey, I see some evidence of some repair work on this guitar.’ He certainly would’ve noticed the extra toggle switches, but he didn’t say anything like that.

“After he inspected the guitar I spoke with Nate, the store owner, and said, ‘That’s not the guitar, but thank you for checking, I’ll see you later.’ So, he sold it to a kid who was working in his music store for $5,000.”

False Alarm?

It turned out, however, that Margouleff and Alenov were mistaken. As Margouleff would learn 20 years later, the guitar was indeed the real deal, but it had been spectacularly refinished to mask the fact that it had been stolen. All traces of the three switches had been expertly obliterated, fooling even a top expert like Alenov. The “kid” that ended up with the guitar was a young punk rocker named Paul “Bleem” Claesgens. He fell in love with the Custom, just as Page did years before.

It was a great guitar – and it was in a store loaded with great guitars. I was just pining for it. I actually ended up owning it longer than Jimmy did!

Paul “Bleem” Claesgens

“I looked at the guitar every day when I walked in,” says Claesgens, who plays in the Minneapolis band Brass Elephant. “I’d pull it off the wall, play it and go, ‘My God, why don’t I own this?’ It was a great guitar – and it was in a store loaded with great guitars. I was just pining for it. One day a credit card came in the mail, and I said, ‘Hey boss, guess what? I’m buying this guitar.’ And he said, ‘Oh yeah, go for it, man.’ I actually ended up owning it longer than Jimmy did!

“I recorded tunes with it. I dragged it all over the Midwest in various bands and even used it to defend myself from flying beer bottles! It’s kind of amazing that Jimmy Page’s lost guitar sat on stages around Minneapolis and nobody knew.”

At some point, Claesgens replaced the guitar’s distinctive Bigsby tremolo with a stop tailpiece, which obscured the instrument’s identity even further. But in 2014, he had a mishap with the guitar that set into motion a series of events that would send the guitar back to its original owner.

One evening, Claesgens was “showing off” when his friends dared him to perform a risky stage move straight from his personal rock and roll glory days. “I took the guitar and whipped it around my shoulder like a hula hoop so it would come back around, which was something I used to do all the time at shows – a total rock star move,” he laughs. “But this time it just flew off, and boom – I looked down and it was broken. The headstock just snapped.”

I looked at it for, like, 20 minutes, but I knew in my heart it probably was really Jimmy’s guitar after all

Nate Westgor

After a quick assessment of the damage, he brought the guitar back to Willie’s American Guitars, where much of this story began. That evening, owner Nate Westgor put the broken instrument on his workbench and, remembering the guitar’s earlier history, just for the hell of it, decided to re-examine it closely.

Thanks to the internet, Westgor now knew about the additional toggles Page had installed on his guitar in the Sixties. He carefully scanned – with a black light – the area where the switches would’ve been, and he was stunned by what he saw.

“The mahogany on the back had actually sunk a bit,” says Westgor, recalling a moment he admits still gives him chills. “The back holes were bigger, but you could only catch it if you turned the guitar at just the right angle in the light. I looked at it for, like, 20 minutes, but I knew in my heart it probably was really Jimmy’s guitar after all.

“I gave it back to Bleem [Claesgens] and told him what I suspected, and I just figured he’d need some time to digest that. Then I got back in touch with Perry Margouleff, and he said, “How are we going to figure this out?”

Black Beauty Rides Again

Margouleff was intrigued with Westgor’s discovery, but he was still not convinced it was Jimmy’s guitar.

He called Page directly and said, “Look, they said you can see evidence where the switches were, but I can’t guarantee it means anything. It could still be a counterfeit. The only way we could really ensure that the guitar is for real is if we could match up the grain patterns in the mother-of-pearl inlays with a photograph.”

When I first met Jimmy over 20 years ago, we went out to lunch and he said to me, ‘I’d like you to find my Les Paul Custom for me’

Perry Margouleff

But the problem was, every existing photo Margouleff had of the instrument was shot with a flash, so the image of the inlays lacked detail. Then Page had a brilliant idea: He went through his archives and found a 60-second film clip from Led Zeppelin’s performance at the Royal Albert Hall in 1970, where the camera man zoomed in on his left hand, making it possible to see the inlay at the 12th fret of Black Beauty with great clarity.

Fortunately, the inlay had a readily identifiable dark stripe – and bingo! “I had a photograph of the guitar that Nate sent me, and the inlay perfectly matched Jimmy’s guitar from the film clip,” Margouleff says.

“I said, ‘Well, fuck, that’s it.’ There’s no chance that two guitars would have that same stripe in the mother-of-pearl in the same spot. It would never happen. When I first met Jimmy over 20 years ago, we went out to lunch and he said to me, ‘I’d like you to find my Les Paul Custom for me,’” says Perry, shaking his head. “It was almost as if he knew I would find it eventually.”

Even though the guitar was a stolen instrument, Margouleff and Page agreed that Claesgens deserved to be compensated. But how much? The $5,000 he paid for it seemed too little. The duo came up with a novel solution. They found another completely clean, vintage 1960 Les Paul Custom with a Bigsby, worth approximately $70,000 in today’s market, and made a swap. While Claesgens was sad to see his companion go, he was satisfied with the arrangement.

Celebration Day

Margouleff carried the missing guitar by hand to England and finally presented it to Page at his home in London. They sat and had a cup of tea while Perry talked about the entire adventure, and then, after about 20 minutes, Jimmy got up and said, “Okay, I can’t bear it anymore. I have to see it.”

I told Jimmy that Bleem and I were so glad to be able to return the guitar to its rightful owner, and that I was still a little nervous that the guitar might not be his

Nate Westgor

The legend then had a Vox AC30 that he had owned ever since his early days in the Yardbirds brought to his house, plugged in the guitar and played it for a while with a smile that refused to leave his face. After having another cup of tea, Perry suggested he call Westgor and thank him personally.

“It was 10:30 in the morning, and I was running late for a dentist appointment when the phone rang,” Westgor says. “It was Perry Margouleff, who said, ‘I’m here with someone who is very happy. Here, let me put him on.’ I said, ‘Oh, Jimmy I’m thrilled to hear from you.’ Suddenly, my voice sounded like I was 15 years old.

“I told Jimmy that Bleem and I were so glad to be able to return the guitar to its rightful owner, and that I was still a little nervous that the guitar might not be his. But he reassured me that when he got his hand around the neck, he knew [it] right away. … Then he said something I’ll never forget: ‘It’s going to be with me [from now on]. It will not leave my side.”

Play It Loud!

But there's another mystery surrounding the Black Beauty. If Page recovered the guitar in 2015, why did it take four or five years for him to reveal it? According to Margouleff, the guitar was so important to Jimmy, he simply wanted a special way to reintroduce it to fans and the world.

“There’ll be a real reason to bring this out into the world,” Jimmy told him enigmatically, “and that’s when people should know about it.” Page was right. That opportunity came in April 2019, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City held an incredible exhibition starring the most legendary instruments in rock and roll history, Play It Loud.

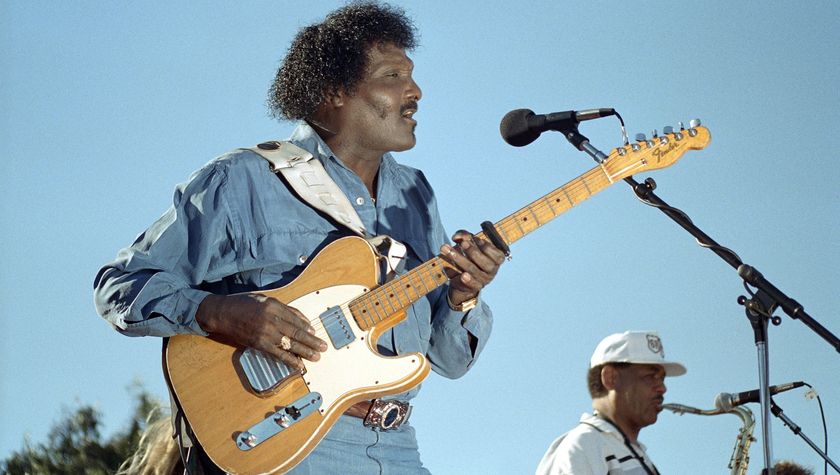

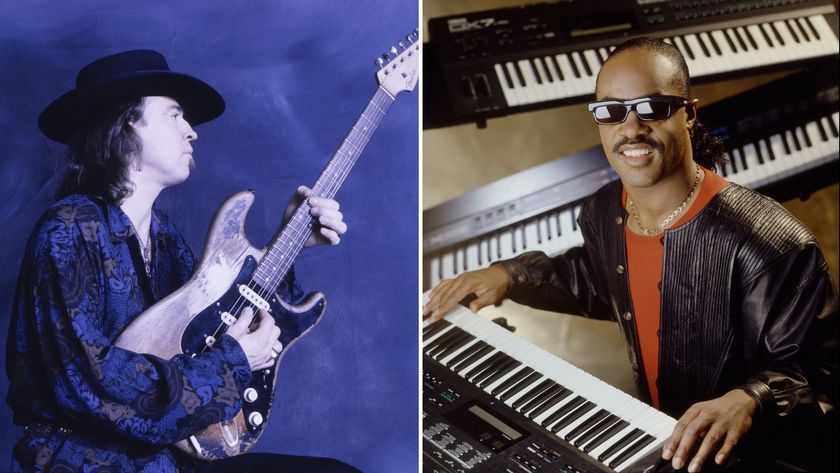

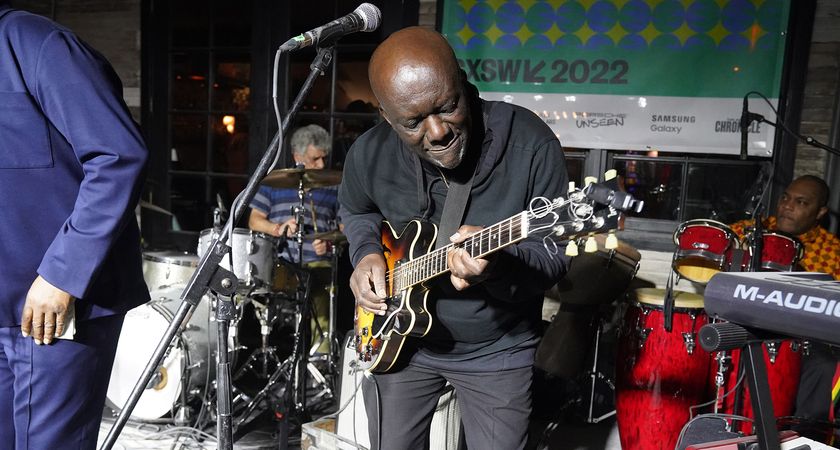

In addition to guitars owned by Chuck Berry, Keith Richards, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Eddie Van Halen, a large portion of the exhibit was devoted to Page’s iconic instruments, amps, effects and stage wear.

And smack in the middle, to the astonishment of his fans, was the long-lost Custom. Like the obelisk on the cover of Led Zeppelin’s Presence, the guitar seemed to have appeared out of nowhere.

Eventually some information about its odyssey began trickling out from Minneapolis, and Page revealed more in Jimmy Page: The Anthology. Now, thanks to Page, Margouleff, Westgor and Claesgens, we’ve finally been able to present the most comprehensive account to date.

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away Brad was the editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. Since his departure he has authored Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.

“When I saw it, I couldn’t believe how cool it was”: Joe Satriani is selling one of his rarest guitars – an ultra-ambitious Ibanez Y2K Crystal Planet prototype

“They’re basically Les Paul copies, let’s be frank. It’s a Les Paul-style guitar and I already have amazing Les Pauls”: Kirk Hammett owns over 100 guitars but none of them are PRS. He explains why

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)